Photo credit: Kevin Day Photography

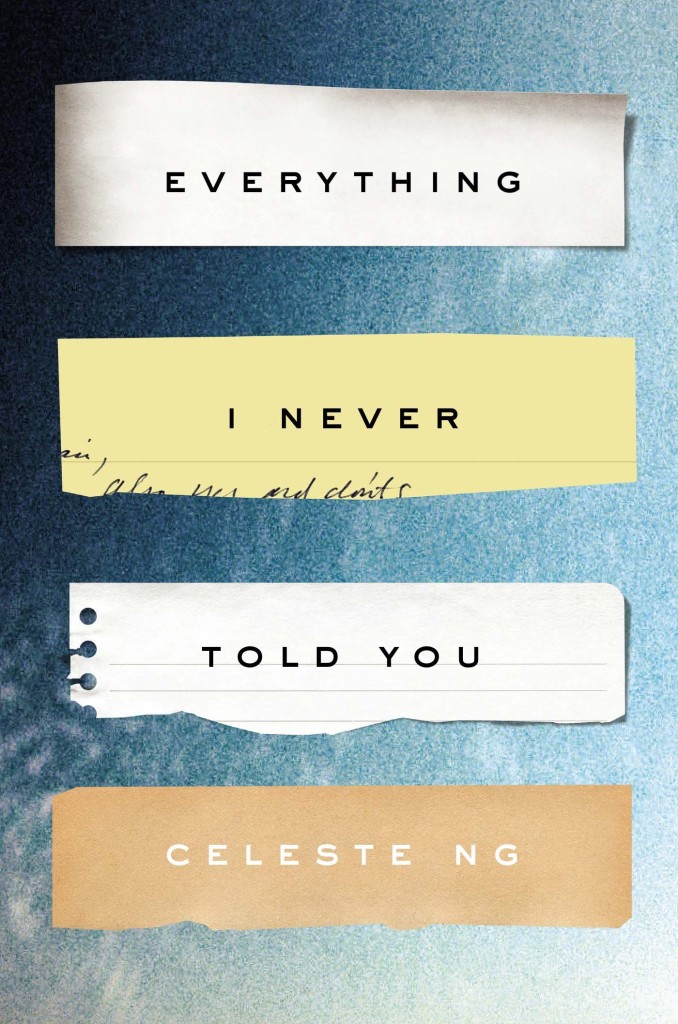

Author Celeste Ng grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Shaker Heights, Ohio before attending Harvard University. She earned an MFA from the University of Michigan, where she received the Hopwood Award. Her fiction and essays have appeared in numerous journals including One Story, TriQuarterly, and Bellevue Literary Review, and she is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize as well. Currently, she lives in Cambridge with her husband and son, and she teaches fiction writing at GrubStreet. Her debut novel Everything I Never Told You, which was published in June by Penguin Press, has received rave reviews from Kirkus, The New York Times and a starred review by Publishers Weekly. In The New York Times, Alexander Chee writes, “If we know this story, we haven’t seen it yet in American fiction, not until now.”

Set in the 1970s in small town Ohio, the novel opens with the death of Lydia Lee, the favorite child of Marilyn and James Lee. A haunting, devastating portrait of a family in crisis, it is also a powerful meditation on identity, desire, and parental pressure as well as the weight of personal history. Jessamyn Ward called the characters “achingly human,” and she observed that Ng’s exquisite writing is “tender and merciless at the same time.” Dan Chaon called the novel “a suspenseful and emotionally complex literary mystery novel, which weaving back and forth in time, unlocks the secrets beneath the surface of family life.”

Celeste Ng talked to Dead Darlings about the novel, her process, the craft of writing, and about the importance of understanding cause and effect when creating fiction or using instinct to find the right tempo.

How long did it take you to complete a first draft? How long did you spend revising?

The first draft took me a little over a year—during which time I also moved from Michigan back to Boston and took (and subsequently quit) a job at a tech startup that was supposed to be 10 hours per week but ballooned to 30+. So I wasn’t what you’d call efficient. Once I quit that job, though, I ended up completing the first draft in a few months of concentrated writing. After that, it took me three more drafts, and almost five more years, to revise.

How much research did you do in general for this novel? What was the most interesting tidbit that you uncovered in your research, but were not able to use?

I did some general research on the different eras in the book, as well as more specific research on key topics, like the Gemini IX space mission, which Nath watches as a child, or how you made a long-distance telephone call in the 1950s. I uncovered a lot of details that I wished I could include but that didn’t have a place in the novel, like the strict parietal rules at Radcliffe in the 1950s that dictated when women could be in men’s dorms. And I learned a lot about pregnancy tests over the years—how the infamous “rabbit” test actually worked, and so on—that the science nerd in me really wanted to work in.

You describe the details of Lydia’s autopsy with a discreet precision that is not too gory, despite the subject matter. How do you prepare to write such a scene and how did you strike that balance?

I looked at some autopsy reports, and I looked at forensics websites and handbooks to find out what happens to the body, physically, after drowning. Those gave me the details: the marbled lungs, the foam around the lips, and so on. Then I had to decide which of those details was most evocative, which ones matched the feeling I was trying to convey as James reads his own daughter’s autopsy report. Lab test results and so on just weren’t visceral enough.

If you look at the autopsy passage, there are a lot of physical comparisons. I tried to make all of it easy to visualize: the foam as a lace handkerchief, the silt in the lungs as sugar, the lungs like dough (so different than what we usually picture). Most of us—if we’re lucky—don’t ever see a drowned body, nor an autopsy report, so it was important to me to make the images as vivid and concrete as possible.

You do an amazing job of blending back-story into the present narrative. How did you strike that balance?

It took a lot of structural rejiggering. I wrote four drafts of this novel, and although the plot stayed relatively constant, the structure changed in every draft. I knew that the past and present needed to be intertwined in the novel itself, because they’re intertwined for the characters, but I went through a lot of revision to figure out how to show that on the page. I tried a multi-part structure, braided timelines, everything, so I’m very happy to hear you feel it works in the final form! If anything, the moral of the story is: keep experimenting until something works.

Hannah, the youngest, is the most observant in many ways. “She would get her father’s jokes, her brother’s secrets, her mother’s best smiles” (p. 22), and she is the one who sees something the night Lydia disappears. What do you think about children and adults in terms of being able to see things as they are as opposed to how we wish them to be?

Hannah, the youngest, is the most observant in many ways. “She would get her father’s jokes, her brother’s secrets, her mother’s best smiles” (p. 22), and she is the one who sees something the night Lydia disappears. What do you think about children and adults in terms of being able to see things as they are as opposed to how we wish them to be?

We tend to think of children as being fanciful and adults as being realists, but I actually think that’s backwards. I’ve always found that adults are more inclined to see things the way they want—maybe because by the time you become an adult, you have a lot of preconceptions of the world that can color your view of what’s actually there. It can be harder to stay open to new ideas, especially if they conflict with what you think you know. There’s a fascinating psychological term for this kind of thing: cognitive dissonance. Basically, that’s the intense feeling of discomfort you get when the world itself and your preconceived notions of the world conflict. You have to resolve that conflict—and it often happens by ignoring or denying what’s there in front of you. (It’s maybe best explained by this Dilbert cartoon, which I actually keep over my desk.) You really want to believe something, so… you tell yourself it’s true.

Children, on the other hand, sometimes see things more clearly than adults do—maybe because they’re still figuring out how the world works. For them, the rules aren’t yet set in stone, and the world is a more flexible place than it is for adults. There are fewer preconceived notions to get in the way of what they actually see, yet children often don’t have the maturity to understand or articulate what they see. I think this is a fascinating paradox—the adults can understand, but can’t see clearly; the children can see clearly, but can’t understand—and such a rich area to explore in fiction. That’s definitely the case for Hannah, in the novel: she observes more clearly than anyone else in her family, but she doesn’t always know how to interpret what she sees.

How do you think being an “other” (being a Chinese student in white Midwestern America, being a divorced home economics teacher in 1950s Virginia, being the only woman in a college chemistry class, or being a family viewed as strange by the neighbors) influences the desires and actions of your characters? Two of the most prominent neighbors and side characters are also viewed as strange by their peers and the world around them. Why did you choose to focus on the Wolffs as opposed to other neighbors?

Virtually all fiction, if you think about it, has an “other” as the central character: someone who’s different in some way. Think about it: Hamlet is the only one knows the truth about his father’s death; against everyone’s advice, he struggles to expose the truth and seek revenge. In To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus Finch takes a stand as the lone defender of an innocent black man (who’s even more of an outsider). In Harry Potter, Harry is The Chosen One, an identity that sets him apart both for better and for worse. This is not to compare my book to these classics, of course, but just to point out that we’re fascinated by the trailblazers, the outcasts, and the rebels. Generally speaking, we’re not that interested in the people who are part of the majority: Everyman tends to be a pretty boring character (and so is Everykid; think Dick and Jane).

That theme of the outsider, someone struggling against the forces of the majority, is really fundamental to storytelling. We often talk about plot in terms of conflict, but another, maybe better, way to look at it is as a search for moments of connection. The outcast is looking for a place to belong; the iconoclast is looking for someone to understand; the rebel is looking for a space to exist. If you look at stories in those terms—and I’d argue that you can read virtually any story in terms of connection and disconnection—then you start to understand why outsiders are so often the focus in fiction.

So I’ve always been drawn to outsiders, and that’s probably why in Everything I Never Told You, everyone in the Lee family is something of an outsider. Everything they go through ends up being shaped by that identity. The same is true of the Wolffs, and the two families are drawn to each other in part because they’re both outsiders.

There seems to be an underlying message that life will change, surprises are certain, that the best laid plans get waylaid in an instant. What unexpected plot twist or character development surprised you the most as you were writing this novel?

Jack’s role in the story was a surprise to me. I thought I was focused on this nuclear family, and then this neighbor boy just kept showing up. He seemed so interested in this family, and I kept trying to figure out why. At a certain point it became clear that he was going to play an important role in the story, but when I realized what it was—and why he did the things he did—it was a surprise to me. But he’s one of my favorite characters in the book, so I’m so glad he found his way into the novel.

Despite being set in the past, you use the present tense. Why?

There are actually two timelines in the novel, the present—which starts with Lydia’s disappearance and moves forward from there—and the past—which starts when Marilyn and James meet and moves forward up to the moment of Lydia’s death. The present storyline is told in the present tense, and the past storyline is told in the past tense. That helped me—and the reader—stay oriented, and know at a glance whether you’re reading a section that happens in the present action of the story or in the past.

Why did you choose to use the third person point of view rather than the first? In a way, it makes each member of the family seem like the central character when the narrative zooms in closely on one member or another, but in another way, it makes the family itself seem like the main character. Was that your goal?

Yes, exactly! I generally prefer third-person to first person because there’s a little more latitude in third person. In first person, I feel like I have blinders and a mute on: there’s so much any given character can’t notice or say because that’s not the kind of person he or she is. But in this case, it’s just what you said: I wanted the family as a whole to be the main character, so the narrative had to be able to both zoom in and give us access to each character’s experience AND zoom out to show the larger picture.

In the novel, Hannah observes that there are many unwritten rules in her family. What are some of your unwritten rules in writing? The things you feel you know instinctively?

I write by ear, so a sentence has to sound right to me. It’s hard to explain exactly what “right” means—though I’m sure you could analyze a phrase and break it into iambs and trochees and so on—but I can hear if the sentence isn’t quite right, and I will keep jiggling it until all the words settle down into the right places. The closest comparison, maybe, is a musician just knowing that the tempo needs to increase here, or that you need to modulate there, and so on. And there’s picking the right image, whether it’s an actual object a character sees or a metaphor. I don’t know how other people decide what images to focus on or what comparisons to make, but that’s another place where I tend to rely heavily on instinct. If an image isn’t quite right, it jumps out at me like a picture that’s hanging askew, and I know I need to come up with something else.

Which dead darling that you cut in revision was the hardest to let go? Which was the easiest?

I’m pretty ruthless about darlings: in general, once I realize a scene isn’t needed, I cut it without much guilt. In the very first draft of the story, I had a long scene—if you can even call it that—in which Marilyn notices a dead bee on the ground, and someone steps on it, and the bee appears to be crushed but then springs back to its original form. This is really something that will happen if you step on a dead bee, by the way (try it). As you can imagine, I saw this happen myself, one summer when I was living in NYC and sitting in Central Park with my notebook. It was oddly beautiful, this bizarre moment of resilience, and I wanted to put it into the novel. But the scene was a page or two long and really had no point—and so I cut it. I’m glad I observed it and I’m glad I wrote it, but I wasn’t sorry to see it go.

One of the hardest darlings to kill was a scene where Nath finds Lydia and Jack hanging out together at the lake, catching tadpoles. If you’ve ever looked at tadpoles—really young ones, just hatched—they’re so strikingly spermlike, oddly sexual and beautiful and virile and creepy all at once. I really liked the tension in that scene, the sexual frisson between Lydia and Jack and the jealousy and protectiveness it awoke in Nath. But it turned out there were better ways to show all of that, and the tadpole scene ended up in the cutfile. That one I did feel a pang over.

As the story unfolds, it becomes clear that events in this book are built on other things, past slights, hidden emotions, old misunderstandings, things never said, even world events such as the space program. Cause and effect seem to rule this world, almost like a chemical reaction, which is interesting as the parents are students of history and science. How do you view these things as catalysts for the plot of the novel?

Cause and effect is something we usually associate with science—but it’s crucial to fiction as well. There’s a well-known bit of E. M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel: “ ‘The king died and then the queen died,’ is a story. ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief,’ is a plot.” In other words, a story is just a series of events—but a plot shows how one event causes another. So actually, every novel ought to be ruled by cause and effect, as you put it. In life, sometimes things just *happen*. But in fiction, our job is to try and impose causality—and, by extension, meaning—between events.

In early novel drafts, there’s often no clear cause and effect for characters’ actions: there’s no domino chain, just a lot of dominoes falling over independently. Elizabeth McCracken has a wonderful exercise, which I found in Naming the World, a book of exercises edited by Bret Anthony Johnston. She suggests that writers try and explain their stories in a series of cause-effect statements: “X happens. Which makes Joe feel Y. Which makes him do Z. Which makes A happen. Which makes Jane feel B. Which makes her do C.” And so on. That really makes you think about how one event in the novel leads to the next and link them into a chain. I give that exercise to my students, and I use it myself, too.

In addition to being a writer, you teach writing. What is your favorite writing exercise, besides the one mentioned above, to assign to students?

My favorite exercises tend to be almost games: I find that if you’re feeling blocked, and you can fool yourself into “playing,” you can get unstuck more easily, and the playful spirit can free your mind up to write things and make connections you wouldn’t otherwise. Here are two that work almost like puzzles:

- Make a list: two people (e.g., a teacher and a policeman), a location, two objects, two adjectives, and an abstraction (e.g., “kindness.”). Or better yet, get a friend to make this list for you. Then write a story involving all of those elements.

- Open a book and pick a word at random. In the left-hand margin of a piece of paper, write that word, then free-associate a list of words in the margin below it, one on each line, all the way down the page. Now write a story (or story fragment), using the word in the margin as the first word of each line. In other words: start the story with your word #1, and craft your sentence so that when you start the second line, word #2 makes sense as the sentence continues… and so on. This sounds impossible, but it’s fun—the prose equivalent of writing a sestina, maybe—and when part of your brain is concentrating hard on the “puzzle,” the censor-part of your brain usually gets overridden. You’ll be surprised at what you come up with.

What was the best piece of novel writing advice you received while studying for your MFA?

One of my professors, Nancy Reisman, told me that sometimes writers need to daydream now and then, and that we should not only accept that, but we should be very protective of that time. I’ve really found this to be true: sometimes, when it seems like you’re woolgathering, your mind is actually very busily accreting images and bits of info that will make up your novel and piecing them together. You may not feel like you’re working, because you’re not actually putting words on paper, but your brain sometimes needs that downtime—scrubbing the bathtub or chopping onions or whatever—to wander. Don’t get me wrong, you also need to sit down regularly at your laptop, which is something I admit I struggle with! But I’ve tried to be kinder to myself about times when I’m daydreaming and “not writing” and to accept that a fallow period now and then is part of the process, rather than slacking off.

What is your next project? Are you currently working on another novel?

I am! I’m just getting back into a project that was on hold while I was editing and promoting Everything I Never Told You. It’s another novel, and I won’t say too much about it because I’m superstitious about things like that. But it will be set in my hometown of Shaker Heights, Ohio—a suburb of Cleveland and a place I love and find fascinating. It’s quite racially integrated and very conscious of race issues, but it’s got a lot of quirks, too—it’s very status- and class- and appearance-conscious. And its history is interesting; it was built on land once owned by the Shakers, a sect that (among other things) didn’t believe in sex, even for procreation. I think it’ll be a fun place to set a story.

If you want to learn more about Celeste Ng or attend one of her readings, check out her website for events and details. You should also check out her interview with writer Heidi Durrow on The Mixed Experience about identity, revision, and readers’ responses.

7 comments