“When someone says you’re overreacting, but you know you’re right, keep reacting until it’s over.”

“When someone says you’re overreacting, but you know you’re right, keep reacting until it’s over.”

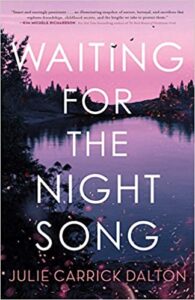

That’s the motto of Cadie Kessler, the protagonist in Julie Carrick Dalton’s debut novel, Waiting for the Night Song. Cadie is desperate to prove an invasive beetle is turning New England forests into tinderboxes. When a secret she long ago buried there comes unearthed, Cadie’s estranged childhood friend calls for help, and Cadie returns to her hometown to confront her past and make amends. But rekindling her friendship with Daniela digs up still more secrets. As wildfires threaten the town from without, farm foreclosures and racial tensions spark within, and Cadie must decide whether beetles are the only truth she needs to tell.

Waiting for the Night Song is both a tender elegy and a fierce protest, a reminder we’re all connected and an ode to the planet we call home together. It has been named to Most Anticipated 2021 lists by several platforms including Newsweek, Buzzfeed, and Medium, and it’s an Amazon Editor’s Pick for Best Books of January. Waiting for the Night Song launches today. Julie and I talked on New Year’s.

John McClure: This novel’s opening tells readers that truth can hide but always emerges. Your protagonist is a researcher facing obstacles to publishing. How did your experience as a journalist inform this novel’s approach to truth-telling?

Julie Carrick Dalton: You can find truth in fiction in ways you can’t with journalism. Obviously journalism’s goal is to report the truth, but as we’ve seen last year in particular, facts can be twisted. As a fiction writer, I have a truth I want to tell and a lot more tools for telling it. Not everything in fiction is made up. The beetles in my story are real. They’re not in New Hampshire yet, but the truth of the beetle and the things that draw it to an environment are real. Novelists can manipulate facts to arrive at truths you might not see if you used only the facts.

Your book reads like a love song to the natural world and a protest in defense of it. It feels like you filled the spaces between facts with a ferocity, a determination to wake people up and worry them.

Yes, worry! The mountain pine beetle has been devastating forests in California and Colorado, causing real fires. These beetles migrate. They’re coming east. I can’t say they’re going to come to New Hampshire and that there will be a fire, but it’s a real phenomenon. As temperatures rise, it becomes more likely that the beetle will expand its territory. I invented how it happened, but I didn’t invent the conditions that make it possible.

And if not this beetle, something else will come. Everything in the environment has to accommodate everything that happens around it. The night song in the title comes from a Bicknell’s thrush, a bird in the New England woodlands that migrates to the Caribbean in the winter. It’s dying there because of deforestation and hurricanes. We are feeling the impact of storms in the Caribbean because this tiny bird is every year coming back in smaller and smaller numbers. It’s just one of many examples.

We’re all connected to things we don’t know we’re connected to. That’s what I wanted people to think about after reading the book.

That theme of interconnectedness appears throughout your novel. Cadie and Daniela vow not to kill bugs because the death of even one might “ruin everything.” How did you balance the fact of climate change’s all-encompassing scope with a novel’s pressure for unity and agency?

Primarily the story is about a fictional town and its people, their relationships with the place and with each other. It’s not a story about climate change; it’s a story about that community and how even an insular town can’t escape the big picture.

Like an intersection in a spider’s web—the convergence of all these threads of character and environment in one location.

When I was thinking of writing about climate, I didn’t want to write about a devastating disaster. I wanted it to be subtle. A story of people living their lives, not screaming about climate change because a beetle came and trees were dying. Climate change is slow and incremental. Despite forest fires and hurricanes growing, many privileged people are spared the biggest consequences of climate change. It allows them to think of it as looming in the future even though, for parts of the world, the apocalypse is here now. We already have more climate refugees than ever before. Acknowledging the tiny disruptions is an important part of readjusting how we view climate change. It makes us likelier to see ourselves in the picture and have more empathy for people who are feeling climate change even worse.

When reading this novel, I thought a lot about rootedness, about our inseparability from nature and place. Even though Cadie tries to escape it, her hometown is in her bones. Daniela’s family immigrates to make a life far from where they were born. How do you think rootedness affects Cadie and Daniela differently?

Daniela’s family doesn’t leave El Salvador by choice, but they make a home in Maple Crest and become an integral part of the community. After the trauma in her youth, Cadie can’t wait to get out of her hometown, but she keeps finding herself pulled back almost on a biological level. I tried to create this sense that she’d been built by the soil she grew up on, the lake water she consumed. When she returns to Maple Crest as an adult, nobody knows she grew up there. She feels like the outsider. I wanted to play with the idea of what belonging means. Home is where you’re from, but it’s also where you choose to be from. They’re not always the same place.

I love that. It matters so much where on this planet we find ourselves, whether it’s by choice or not, because we’re limited creatures. Wherever we arrive, what really defines us are the people and places we devote ourselves to.

Devoted is a good word. Even though Cadie identifies her trauma with the town, I think she can’t break that bond. When beetles and fires threaten Maple Crest, she has a visceral fear of losing this place she feels is part of her.

When I was 11, I was Cadie. My family had a lot woods, and my best friend and I traipsed around there with walktie-talkies, making up adventures. As I wrote scenes with young Daniela and Cadie, I was roleplaying how my friend and I would have responded.

There was this creek we’d play in all the time with a looping vine hanging above. You could put your foot in it and swing out over the water. By high school, this friend and I had grown apart, but one day I was upset about something, and I went back into those woods by myself. Someone had taken an axe and sliced through the vine, and I remember being so wounded that somebody would damage my world like that. I sat in the woods and cried. It was just a vine, small in the grand scheme of things, but it felt enormous. I’m very attached to places like that. I think I was drawing on that kind of a wound a bit.

Speaking of wounded things, I have to ask you about when Cadie hits a bear with her car. She says, “Everyone should have to face the things they kill.” Then she approaches this dangerous, dying animal. I loved how the scene dramatized the environmental stakes. Where did it come from?

Around when I started this book, I was driving down 95 from New Hampshire to Boston. My son was asleep in the backseat. Ahead of us, this teenager hit something in the road, pulled over, and walked to where a dead bear cub lay. As I passed him, I started thinking there must be a mama bear watching nearby. By the time that fear entered my brain, I was too far away. I felt horrible that I didn’t have the reflex to recognize it faster and warn him. It was killing me the whole drive home and made me ask: what does it take to notice danger and do something brave?

That afternoon, I wrote the bear scene to work through it. Later, I was outside with my son by our lake. Five girls about eleven years old were out in a canoe without life jackets when they capsized. None of them left the boat because they were afraid they’d get in trouble for sinking it. Across the lake, people saw the girls screaming and shouted that they’d called the police, but nobody went in, and I thought, “I cannot do this twice in one day.” So I got in my kayak and pulled all five girls out. If I hadn’t gone through the guilt of not intervening to help the kid with the bear, and I hadn’t written the scene and thought through the question of when do you help a stranger, I don’t think I’d have gone in the water after those girls.

That’s one of the reasons I love fiction—the dramatization of philosophical dilemmas. It feels like a way of practicing who we are and who we want to be.

Exactly right, but for the purposes of fiction, you can’t wedge something in because it matters to you. It has to fit the plot. Everyone in my Novel Incubator workshop thought the bear didn’t belong, so I cut the scene. That was the hardest thing I did in editing the entire book. After I took it out, I rewrote the book. At a moment in the story where Cadie has to face what really matters to her, I was driving along with her and the bear just walked out, and I knew that was where the bear belonged.

Stories are a central part of Cadie’s journey. She and Daniela sneak books to a boy in distress—rescuing him, Cadie imagines. But Daniela accuses Cadie of doing harm with her fantasies. Is that the challenge of truth in fact versus truth in fiction? How do stories and justice fit together for you?

There is power in fiction to underscore the truth or subvert it. I had a reading list of about forty books I felt this boy must read. Like he was a vessel I was filling with all the stories I wanted to build a human being out of. It mattered to me what books I was sharing with Cadie, and it mattered to Cadie what books she was sharing with him because there were little pieces of truth in all of them. I felt a lot of responsibility to the characters to choose well. In the end, I removed books from the list that weren’t the truth I wanted to share with my characters and readers.

There’s such intimacy in sharing stories. In fantasizing together, we affirm our mutual commitments and values. Maybe that’s where truth in fiction originates, in the multiplicity of perspectives making us into people capable of seeing from many angles. Maybe you are what you read.

That’s kind of what Cadie feels, like she’s rescuing this boy by giving him a world. That’s a reflection of me and my childhood friend. We’d make up stuff all the time. For Cadie, stories are the biggest way to save somebody.

Now that your debut is going out into the world, what stories are next for you?

My second book, The Last Beekeeper, is coming out in early 2022. It’s set in the very near future after the collapse of the pollinators, which sends the world into agricultural and economic chaos. The book is about the relationship between the last beekeeper and his daughter, about reconciling events before and after the collapse. I’m really excited about it because it gave me room to play with science even more than I did in the first book.

You keep bees, right?

I love bees, so I’m loving writing those parts, but I don’t have an active hive right now. That was the motivator. I was trying so hard with my bees, and I thought I was doing all the right things. I loved them, and they died. It’s heartbreaking how, all over the place, hives are collapsing.

Julie Carrick Dalton has published over a thousand articles in publications including The Boston Globe, BusinessWeek, The Hollywood Reporter, Electric Literature, and The Chicago Review of Books. A Tin House alum, 2021 Bread Loaf Environmental Writer’s Conference Fellow, and graduate of GrubStreet’s Novel Incubator, Julie holds a master’s in literature and creative writing from Harvard Extension School. She is the winner of the William Faulkner Literary Competition and a finalist for the Siskiyou Prize for New Environmental Literature and the Caledonia Novel Award. Julie is a member of the Climate Fiction Writers League and a frequent speaker and workshop leader on the topic of Fiction in the Age of Climate Crisis. Mom to four kids and two dogs, Julie also owns and operates a small organic farm.

1 comment