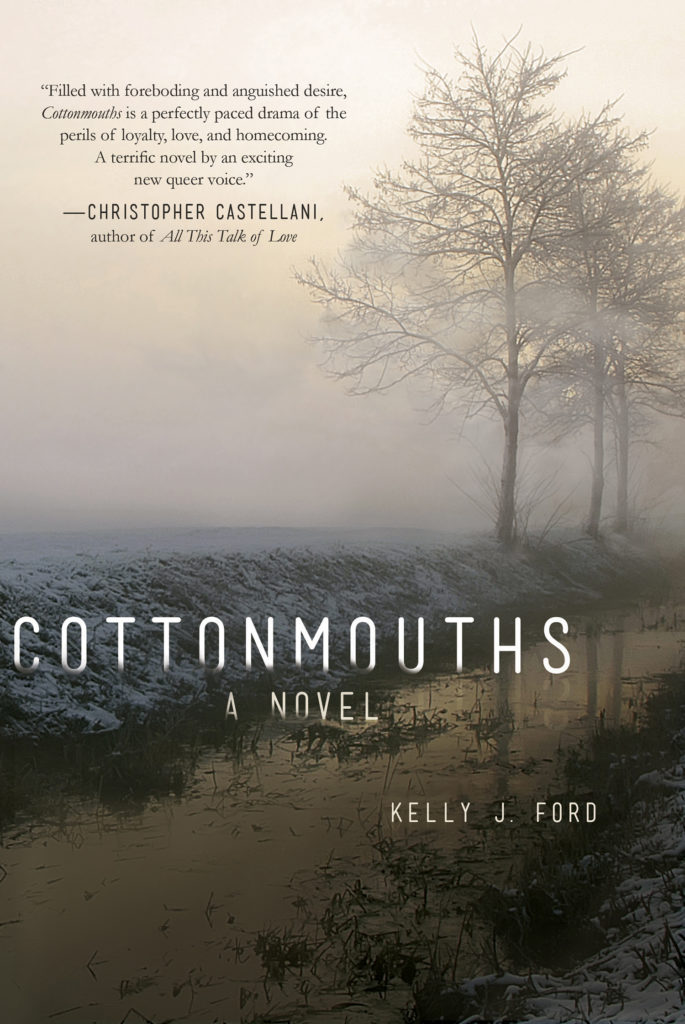

Kelly J. Ford’s gripping debut novel, Cottonmouths, recounts protagonist Emily Skinner’s return to her small hometown in the Ozarks. Emily’s irresistible attraction to her former best friend and childhood crush Jody Monroe leads to danger – a meth lab on Jody’s property is just the start. According to Christopher Castellani, Cottonmouths is “filled with foreboding and anguished desire . . . a perfectly paced drama of the perils of loyalty, love, and homecoming.”

Kelly J. Ford’s gripping debut novel, Cottonmouths, recounts protagonist Emily Skinner’s return to her small hometown in the Ozarks. Emily’s irresistible attraction to her former best friend and childhood crush Jody Monroe leads to danger – a meth lab on Jody’s property is just the start. According to Christopher Castellani, Cottonmouths is “filled with foreboding and anguished desire . . . a perfectly paced drama of the perils of loyalty, love, and homecoming.”

Kelly is a graduate of GrubStreet’s Novel Incubator program. Her fiction has appeared in Black Heart Magazine, Fried Chicken and Coffee, and Knee-Jerk Magazine. Originally from Fort Smith, Arkansas, Kelly now lives near Boston with her wife and cat. Cottonmouths is available at IndieBound, Amazon, and Barnes & Noble. She took time out from her launch to speak with Dead Darlings about her new release.

Dead Darlings: What has led to Emily’s premature return home during the opening pages of Cottonmouths?

There’s a set order of events that’s expected of Emily, much like the Game of Life: go to school, get married, have babies, get rich, retire. I firmly believe the Game of Life – with its colorful spin wheel, draw cards, and blue/pink accessory pegs – is responsible for so much heartache in America. We were totally duped! We’re taught this pattern, and if you deviate from it, then there’s something inherently wrong with you.

Emily takes a detour in the Game of Life by quitting college halfway through. She’s not passing her classes and college life isn’t for her. She knows that she needs to do something with her life, but she doesn’t know what – and she’s carrying around the emotional baggage of being queer in a house with a mother who is very much a fan of “don’t ask, don’t tell” where Emily’s sexuality is concerned.

She’s also struggling within a declining economy where the employment options are limited, particularly in rural America. When Emily loses her scholarship, she can’t afford to stay in school. Her loans won’t cover it. There’s no other option but to make the best of a bad situation and move back home to Drear’s Bluff to live with her parents until she can figure out what next. In the midst of all this frustration and angst, she unexpectedly sees Jody Monroe, the one good thing she remembers about Drear’s Bluff. The pull of that connection is too much to resist and leads her down the road to Jody’s house instead of home.

Emily tells herself a lie within the first couple pages of Chapter 1: “Soon, though, she lied to the empty passenger seat, she’d get a call for a job she really wanted or some other professional job she didn’t really care for, but at least it would be a real job, something that could make a dent in student loan and credit card accounts that sat on the brink of default and whose balance kept her up at night.” Can you explore the importance of lies and lying in this book?

Lying is part of the social contract in Drear’s Bluff, as is the case in so many close-knit communities and families. There are things that people aren’t supposed to know, but there are just as many back channels to learn the things that people want to hide. For Emily, these lies are also a way to feel better about her situation, though she knows deep down that she’s not going to get that job that will help her out of debt or her parents’ house. Lying to herself makes the truth easier to swallow.

Shame is at the heart of all the lies in Drear’s Bluff: over poverty, economic downturns, drug addictions. The list goes on. These things stare people in the face, but everyone pretends not to see it. To see it means they might have to do something about it. But then they might have to admit there’s a problem, and that takes work. So what do they do? They either lie or ignore it and pray for God to make things better. But, as Emily learns, prayer doesn’t always work.

Who is the troubled woman at the center of Emily’s obsessions, Jody Monroe?

To the people of Drear’s Bluff, Jody Monroe is nothing but trash, just like her mother. She’s the “bad girl,” a defect of genetics passed down from a mother who is considered the “town whore” and a father who is a mystery. The Monroes are the opposite of good Christian folk.

In every small town, there seems to be that one family who can do no right. Think of the Averys, the family at the heart of the Netflix documentary Making a Murderer. Or, as Gillian Flynn’s protagonist Libby Day says in Dark Places, “I couldn’t remember why the Evelees were bad. I just remembered they were.” The apple falls right next to the tree and nobody expects that to change.

I wanted Jody to be so much more than the trash that people think she is. I’m always interested in figuring out how people end up in unusual or criminal situations. I do believe that most people are inherently good but can ultimately “go bad.” There’s a moment that changes everything, a door of no return, a bell that can’t be un-rung. I’m always looking at my characters’ lifelines to figure out where things changed for them and why. Why did they choose this path versus that one?

For Jody, that point is early on in her life when her mom consistently leaves her. That lack of maternal and paternal care shapes who she becomes and how she reacts. Jody must fend for herself. So much of what informs Jody’s life and her decisions begin in childhood with neglect and continue into adulthood with class complications and social designations that she can’t move beyond.

Much like Jody is affected by her mother, Emily is affected by hers. Over the years, Emily’s mom, Dorothy, very much wanted to save Jody’s mom, literally, at church. Though none of her efforts worked, Dorothy still has that goodness and that need to save people – if somewhat misguided – within her. Emily unwittingly inherits her mom’s bad habit and repeats the pattern with Jody. Jody becomes the person that Emily wants to save, but she also wants to be saved by Jody.

One of my favorite scenes in the novel’s opening chapters takes place in church, where “most of the spaces were filled and the sun had climbed past the steeple to wash the building and lawn in harsh daylight.” Emily’s physical and emotional claustrophobia are so palpable here. Can you talk about what it took to construct that scene?

Though the church, Drear’s Bluff, and characters are purely fictional, so much of that scene is built on my memories of being an outsider in the churches my friends dragged me to as a young adult.

Someone was always trying to save me. I was the bad girl that a lot of other kids weren’t allowed to play with – I had dirty jeans, told dirty jokes, had ratty hair, and didn’t have a curfew. Still, the good girls were drawn to me, maybe because I was quiet and didn’t have many other friends, which meant they had my undivided attention. To be their friend, they had to vouch for me to their parents. When my friends’ parents learned that I didn’t go to church, they insisted I go with them. Getting saved and accepting Jesus as my personal savior – that was their ultimate goal. I only got saved once, so they’d stop bugging me about it.

I didn’t realize I was gay until I was well into adulthood. So I had to imagine what it must be like for this queer woman to be stuck in this environment that tells her at best that she’s wrong and at worst that she’s going to hell. For Emily, church is the price of admission for moving back in with her parents. Their house, their rules.

Like much of the South, church culture is a huge part of people’s lives in Drear’s Bluff, whether they’re a churchgoer or not. Church influences the local news and commercials, Facebook comments, which TV shows are appropriate or not, whether you’re able to adopt, get married, live your life openly. When you grow up in that environment, you learn to keep unmentionables – whether it’s a distaste for religion or your sexuality, in Emily’s case – under wraps. It’s a survival mechanism: intrinsically claustrophobic, but especially so under a steeple.

In addition to lying, a lot of judging happens in Cottonmouths. What is the role of judging in Drear’s Bluff?

Much like the lying, judgment is a byproduct of shame in Drear’s Bluff. Addiction is a way out for many, and it takes many forms. While some in Drear’s Bluff rely on food, alcohol, pain pills, or meth, others rely on that good old caste system of the good folks vs. bad. Think of that old saying about how the husband kicks the wife and the wife kicks the kid and the kid kicks the dog. To feel better about themselves – their flaws, their faults, their broken dreams – they ignore their own circumstances and imperfections and instead find someone else who is worse. Because if someone else is worse, then you might not be so bad. Nobody really wants to be the family with the bad reputation – like the Monroes – that everyone uses as their yard stick: well, at least we’re not that bad.

You’ve mentioned Jeanette Winterson and Sarah Waters, two prominent lesbian novelists, as influences. Can you talk about how your awareness of LGBT-informed literature developed as a reader, and as a writer?

I discovered Jeanette Winterson’s Written on the Body while browsing the shelves at Trident Booksellers in Boston shortly after I came out. Before then, I hadn’t read anything by a queer author – at least not that I was aware of. I was not socially conscious or politically aware when I came out. I was truly green and felt like a teenager all over again, with all these confusing emotions to sort out. That book was a revelation. There’s something so powerful in seeing yourself in literature and pop culture. You exist. You matter. You aren’t alone.

Along with Jeanette Winterson and Sarah Waters, I was deeply affected by the writing of Kate Chopin and Maya Angelou. Their work showed me that there’s a place in the world for women who fall outside the traditional feminine norm.

I’m writing towards my obsessions: this intoxicating stew of shame, sexuality, Christianity, and crime. I’m writing the books I want to read. I include queer characters because I’m reflecting my world and the stories that matter to me. If my story resonates with a queer reader, then that’s gold. If a non-queer reader better understands the restrictions that queer people live under due to religious and societal norms after reading my book, then that’s a bonus.

Where are we in the long evolution of LGBT fiction moving into the mainstream? How conscious are you of writing for a LGBT audience?

We’re further than we’ve been, but queer writers and stories still take up a small piece of promotion and shelf space in traditional publishing. As a writer and reader and citizen of the world, I appreciate the YA community for opening up the diversity dialogue. There’s far more transparency of minority lives as a result, including those in the LGBTQ community. More agents and publishers seem to be open to these narratives.

With fewer queer narratives out there than for the majority straight audience, I try to be mindful of existing tropes associated with queer characters and think about how my story and my characters might be received. I interrogate the story to see if there are any issues. I don’t think of it as self-censorship so much as being honest about my work and asking, “Do I want to put this out into the world?”

If it’s bullying or a hate crime or something truly harmful to a teen whose hands my book might end up in even though it’s considered adult fiction, the answer will often be no. Those narratives have their place. Without them, you risk erasure of the violence wrought upon our community. But I’m not always going to be the right person to tell that story. This forces me to take left turns and subvert expectations in my own work, which is more interesting to the story in the long run. But there are exceptions. In Cottonmouths, I use a slur that I really struggled with. In the end, it was the most appropriate for the story. I’d love to see LGBTQ literature evolve to include more than the hurt, but first the rest of the world has to do its part in making it a safe space.

One of our Boston City Councilor members, Ayanna Pressley, spoke recently at the Boston Write-In: “No one wants to be tolerated. They want to be understood.” She was speaking specifically about immigrants and refugees, but her words resonated with me as a queer writer. Tolerance is the lowest level of acceptance. I don’t want to be tolerated. Compare:

Thank you for tolerating me.

vs.

Thank you for understanding me. Thank you for including me.

Without that empathy, it’s going to be a hard ride. Literature will help lead that charge, but we need non-queer readers and authors to come along as well.

Cottonmouths is pitched as having echoes of Daniel Woodrell, who coined the genre “country noir” to describe his own writing. Does Woodrell’s label apply to your work?

Daniel Woodrell initially used the term to situate readers: “The concept of country noir really was just to place it in a rural – instead of urban – setting and bring some of the things attached to that kind of story to bear, just as a change of pace really.” He’s since gone on to say that he doesn’t use the term anymore. “Noir” has a specific expectation: hard-boiled detectives and whatnot.

Daniel Woodrell initially used the term to situate readers: “The concept of country noir really was just to place it in a rural – instead of urban – setting and bring some of the things attached to that kind of story to bear, just as a change of pace really.” He’s since gone on to say that he doesn’t use the term anymore. “Noir” has a specific expectation: hard-boiled detectives and whatnot.

I prefer to consider my work in the vein of grit lit, though even that term is loose. But it seems to fit according to Tom Franklin, who co-edited Grit Lit: A Rough South Reader with Brian Carpenter, elaborating that “it’s people using weed and pills and sometimes meth. They’re usually white, usually rednecks, Snopesian. Broke, divorced, violent – they’re not good country people.” One of my favorite grit lit novels is The Devil All the Time by Donald Ray Pollock. It’s dark and violent and depressing. Those are the stories I like to read and write.

Beyond that, Cottonmouths, though set in the South, is not what I consider the country. The country sounds so nice: full of sunshine, beautiful farmhouses, big smiles, and good Christian people. I always joke that nothing bad happens in a country song. People break up and people die, but that happens to everyone. They’re mostly partying in their pickup trucks and really just want to be loved, okay?! There’s a lot more darkness out in the sticks than what most people are aware of. (That said, I love country music.)

Cottonmouths is primarily set in the backwoods. The backwoods are far more ominous to me than the country. You never know what you’ll find out there. Weird signs tacked to trees. Parked cars along the creek with occupants who look like they’re about to commit a crime. Rough kids walking along dirt roads with shotguns. A friend once found a tent full of dismembered mannequin parts on the edge of her family’s property. Creepy. But great material if you’re a writer.

What was it like editing Cottonmouths, a novel set in the rural South, while living in Boston? What changes do you notice these days when you go home?

I left Arkansas twenty years ago, but the impact of place reverberates within me still. Arkansas and the South live within me. They’re a part of my bones. Any time I opened my book to work on it, I was right back in the sticks and those hot churches with people who wanted to save me. That feeling never goes away. I return to Arkansas once a year, and I still have to emotionally prepare a week before, and plan for recovery after.

The changes I see are primarily in buildings and landscape. The downtown area of Fort Smith is now a street art haven, which is shocking but cool. The people and culture seem very much the same, but I’m not there enough to really say. I still follow the local news stations to see what’s going on locally. The headlines and commentary make me laugh — also, great story material.

In a way, it’s just the same old, same old, except social media is a megaphone. The shit you hear people yelling in the Comments section are the things I’ve heard people yelling in homes across the South and in certain sections of Boston. The difference is now I see it in public forums instead of hearing it behind closed doors.

What role did Grub Street’s Novel Incubator program play in shaping this novel?

The Novel Incubator program opened my eyes to craft and the importance of deep revision. Nothing beats having ten other people review your entire novel and give you feedback on plot, structure, character development, and pacing.

It really does take a village to bring a book to market. The amount of emotional and promotional support we get from the alumni group is unparalleled. It’s a beautiful thing to look out into an audience and see the faces of your writing tribe, and to show up for them and spread their good works to the reading public when it’s their time in the spotlight. It’s been deeply satisfying to be a part of this community.

Can you talk about how the teaching process informs your own writing nowadays?

The great thing about teaching is it forces you to continuously learn and read with intention. I’m especially interested in reading and sharing work from more diverse voices than were included in my studies. There are so many terrific stories being told in inventive ways in contemporary fiction. That inspires me to take chances in my own work and to try something beyond my personal safety lane of 3rd person close, from one point of view.

More than that, I love to help emerging and aspiring writers pursue their dreams, whether through teaching fiction at GrubStreet or acting as mentor to current Novel Incubator students.

What goals do you have in promoting Cottonmouths? How are you going about building audience?

In my day job, I work with a lot of small business owners who focus on local marketing while headquarters focuses on national media. Even though my book is not just for a local market, a lot of what I’ve learned translates to promoting my work. Authors are also small business owners. By focusing on targeted marketing, I’m hoping to build interest that will cascade into other regions and spread like the virus in Contagion. All Gwyneth had to do was shake one infected hand and BOOM. Everyone’s infected. That’s my goal for Cottonmouths. 🙂

Seriously, though, one of the best learnings from my small business colleagues has been around quality and personal interaction. Customers like to know that there’s a person behind a brand. I certainly do. I still get a thrill when I go to a book reading and hear someone speak. If they’re funny and engaging, in addition to just buying their work, I immediately want to be their friend. This happened at the last Craft on Draft reading series with Sara Farizen, who writes queer YA. She was hilarious and charming and I all but asked her to be my new best friend. Because I’m nothing if not awkward.

What’s next?

I’m currently working on another novel. Other than that, I’m prepping for readings and focusing on enjoying the debut author ride.

To learn more about Kelly and her upcoming events, follow her on Instagram and Twitter.

4 comments