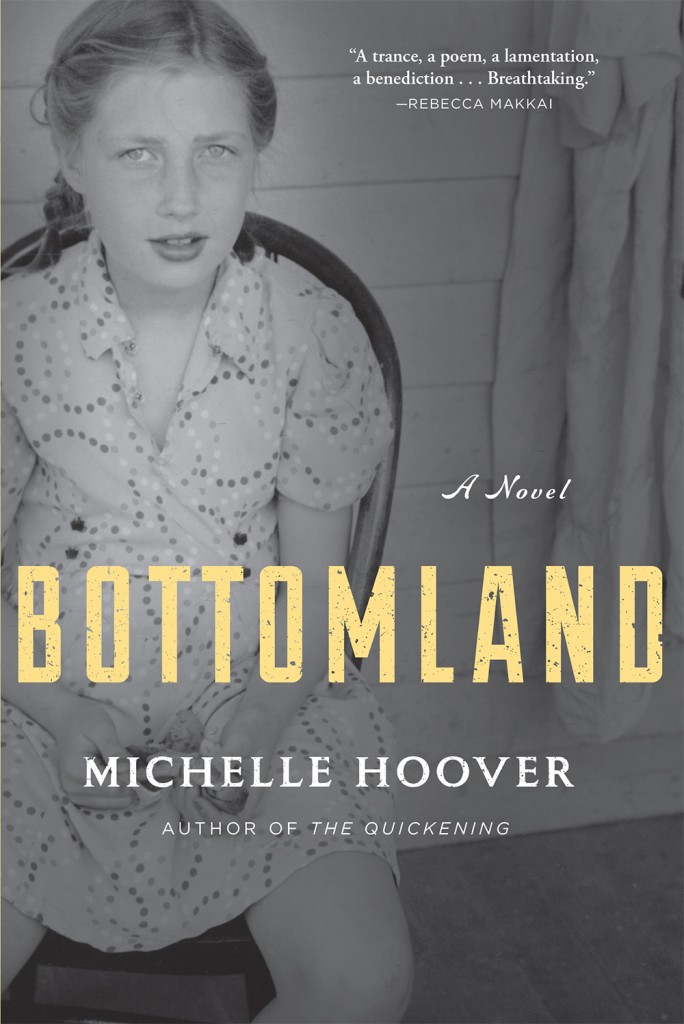

Building on her critically acclaimed debut novel The Quickening, Michelle Hoover’s gripping, brilliantly crafted new release, Bottomland, follows the Hess family’s struggle to stay together on the Iowa plains following the mysterious disappearance of two family members during the years after World War I. According to Daphne Kalotay, “Bottomland is alive with secrets, hard choices, and the acute costs of independence.” Jenna Blum has compared Hoover’s work to Dreiser and Cather.

Building on her critically acclaimed debut novel The Quickening, Michelle Hoover’s gripping, brilliantly crafted new release, Bottomland, follows the Hess family’s struggle to stay together on the Iowa plains following the mysterious disappearance of two family members during the years after World War I. According to Daphne Kalotay, “Bottomland is alive with secrets, hard choices, and the acute costs of independence.” Jenna Blum has compared Hoover’s work to Dreiser and Cather.

Matthew Gilbert, in his Boston Globe review, wrote, “There are many compelling things about Michelle Hoover’s potent new novel, Bottomland, not least of all her austere style and its visceral punch. Seriously, you might feel a few chills run up your spine while reading, as Hoover delivers stark passages about the frigid desolation on an Iowa farm in winter….But what struck me repeatedly is the way Hoover’s story, set largely in the immediate wake of World War I, has so much contemporary resonance.”

Michelle is the Fannie Hurst Writer-in-Residence at Brandeis University and teaches at GrubStreet, where she leads the Novel Incubator program. She is a 2014 NEA Fellow and has been a Writer-in-Residence at Bucknell University, a MacDowell Fellow, and a winner of the PEN/New England Discovery Award. The Quickening was a 2010 Massachusetts Book Award “Must Read.” A native of Iowa who lives in Boston, Michelle took time out from her launch to speak with Dead Darlings about her latest novel.

Dead Darlings: Bottomland starts as a mystery: what happened to the two youngest Hess sisters, Esther and Myrle? What attracted you to this story problem, and what kept you engaged through the process of drafting and revising?

Michelle Hoover: I often tell my students to follow the character’s desire or to create an overarching dramatic question to provide a spine for their books. It’s the easiest way to write a novel. There are others, of course. And there are far more important things on that spine. No one wants to see a novel walking around by its naked, boney self. The question of what happened to the sisters became my dramatic question, one I knew I could and should follow from the beginning of the book to its end. The structure is otherwise complicated, jumping perspectives and periods of time, but the spine remained the same.

My own questions about the story kept me engaged. It was based in part on a family legend, but the legend is sketchy, contradictory. Still, there was a mystery there that I wanted to figure out, even if it diverged from what actually happened. I knew that, of the two daughters who go missing, only one comes back. I also knew that it’s the younger of the two—the seemingly submissive and innocent Myrle in contrast to Esther who is mischievous, wild—who never returns. The outcome was the reverse of what I expected. So how did it happen? What turned the younger sister desperate? What made her the risk-taker? And what compelled the older to long to go home? It was a puzzle for me and I kept writing and rewriting, deepening the characters and my understanding of their experiences, until the pieces fit.

Time structure in Bottomland loops back forth from narrative present to past and back again. What led you to this approach, and how did you maintain continuity through five sequential narrators?

The dramatic question again. I think that’s what gives the five sections their continuity. But what led me to all those jumps? I guess the book just needed to go there. Parts of the story run back to the father’s immigration in the 1890s, and the ending goes as far forward as 1987. The heart of the book, though, is 1920, so I kept circling that year to stay sane.

The first section of the book, narrated by the oldest daughter, begins when the two sisters go missing. 1920 again. But then the dilemma: I wanted to show what the family had experienced before this event, and how those experiences influenced and may in fact caused the girl’s disappearance. Flashbacks in general are weaker than present-day action. But in the second section, I was able to sneak in the father’s story of his arrival and homesteading by simply beginning his narration further back in time. It doesn’t work as a flashback that way, but keeps the strength of present-day writing. And I had tried to make the reader curious about those past events so they’d be willing, even eager, to go with me.

In the third section, the youngest brother’s, I had already set up a journey for him in the novel’s beginning—to search for his missing sisters. His section also begins before the present-day part of the story, but I had the forward motion of his search to carry the reader through. The novel keeps working like that, like a spiral, spiraling forward around that harder, straighter spine that is the dramatic question. The question itself grows and complicates as the book continues, but it’s always there in the background, no matter what.

The responsibility for telling the Hess family’s story falls to five family members in sequence, each with a distinct voice and agenda. What special opportunities and challenges did you face in using this narrative strategy?

The responsibility for telling the Hess family’s story falls to five family members in sequence, each with a distinct voice and agenda. What special opportunities and challenges did you face in using this narrative strategy?

I knew the choice would be difficult—and it was, ridiculously so. I imagined the family house to be like a set of boxes, each family member boxed inside, separate from the others. Because of the way the family had been ostracized from the town and abused, the father maintains a tight watch over his children’s comings and goings and keeps many of the doors in the house locked. So I wanted to use five perspectives that also seemed locked inside themselves, in a way only the first person can do—in its limitations on both style and knowledge. The divisions between family members needed to feel absolute, divisions that drive each to choose between love and self-preservation as the novel continues. After World War I, the time period of the novel, American life was itself deeply divided and undergoing constant change—the surge of science, the hope of modernization, the achievements of the feminist movement, the rottenness of war. I wanted this time period, along with the setting, the family unit, and the individual characters, to mirror each other as much as possible.

To get it done, each voice needed to have its own cadence, its own language, its own personality. That was hard enough. Of the five, it was the voice of the father—a first-generation German immigrant—that nearly killed the idea. I wanted a hint of that accent, but not so much that it became comic. I didn’t have a natural ear for what I wanted, so I had to jump through some hoops. Initially I wrote the voice in English, reworked the sentences to follow German syntax and include common German-to-English errors. That process took a good bit of schooling and research, but the result was nonsense. So I worked backwards, slowly re-aligning the sentences to proper English again. In the end, I wasn’t sure if any hint of the German remained. Thank god readers in the last few months have told me otherwise.

I don’t think I’ll try such a thing again. I certainly don’t encourage my students to attempt it. But writers like to give themselves narrative challenges. Sometimes these challenges make the book feel truer, or more intellectually satisfying to create, and sometimes you just have to beat your head against that wall until you get it right.

Your lead-off narrator, Nan, bears a lot of responsibility within the Hess family after her mother’s death. As a character she also carries the weight of unraveling her sisters’ disappearances. Can you talk about the process of rendering Nan’s character?

Nan was the easiest character to write, actually. She came to me first. Initially her voice was fast, as she was reeling from the disappearance of her sisters and essentially telling the reader everything at once. So even though I had her voice, I also needed to slow her down. She has to introduce each of the other characters, introduce the family life, maintain her own search for the girls, while also maintaining the family basics—meals, clothing, cleaning, field labor, and budgets. She has to keep everyone’s emotions in line and be the voice of constant reassurance. Essentially, she takes on the mother’s role, because the mother died toward the end of the war.

This of course isn’t a position she wanted, but it’s one she was handed, very suddenly, at a time when she had just gotten engaged and was beginning to imagine an independent life. Beyond all the things she has to do, all the expectations placed on her, she actually wants something very different. So while on the surface she has to keep up her good graces to hold the family together, underneath she’s burning with loneliness and a sense of futility.

I think any well-developed character carries that doubleness—what they show to the world and who they truly are beneath the costume. It’s usually part of the character’s journey to eventually reveal their true selves to the world of the book and to us. The story should push them to the point that they must tear off that costume—and some happily do so.

As someone with a deep grasp of rural habits, customs, and place details, what was it like researching Chicago as a location? And what was the process of situating Bottomland in this particular moment of American history, the period during and immediately following World War I?

Chicago was a different writing experience for me, certainly. But also not. Cities have their own messy terrain, and with the kind of work my characters were doing in the garment factories of the time, I still had a chance to get my characters sweaty and dirty and good and aching tired—the same as I’ve always done for my rural characters. That kind of work, it reveals something human and basic about a person. I think that’s why I like it. I think I’d kill myself if I had to write about characters in a contemporary office setting. I just wouldn’t know what to do with them.

Initially I planned to base the story around the Second World War. That’s when I thought anti-German sentiment was at its highest. I was wrong. I discovered the Babel Proclamation then, a law passed by Iowa’s Governor Harding in the last months of the war. It declared all foreign languages in the state illegal, both in public and private. Other states had similar laws, but most kept theirs to the public sphere. That find alone made the decision for me. World War I was the greatest test for my characters in very specific ways, and even more specifically for my chosen setting.

To get the factory work right, I scanned as many photographs as I could find of early 1900s garment factories, or basically any kind of factory that worked on such an industrial scale. I also read diaries and letters written by garment workers, both past and present. I did the same for my details about the war. I needed the youngest son’s service experience to be as palpable as possible, and to get those kinds of particulars, I’ve always considered first-person accounts best. For instance, the history books tell you that the derogatory term for the Germans, Jerry, wasn’t very popular in World War I, but I found letters that proved otherwise.

Truthfully, the Internet is a wonderful thing. I no longer consider it the tool of a lazy researcher. (Though I did have to make a quick trip to Cleveland, the city I originally chose for the setting of the book’s final third. I realized the city wouldn’t work the way I needed. Feet on the ground is always best, though writers can’t always afford it). I needed detailed maps of Chicago as well as of the ‘L’ system. (And guess what? You can find a map of the ‘L’ as it was in 1920. How can you beat that?). I needed information about the train lines that ran through Iowa and Illinios during those years, as well as how much tickets cost and what the ride was like. I found payroll information, the cost of livestock. I found out what milk straight from a cow actually smells and tastes like from a contemporary blog kept by organic farmers. Oh, and I learned how to skin a rabbit. YouTube. There’s a frightening number of videos on YouTube about that.

You’ve spoken before in public and in print about your attention to sentences and language. One aspect you’ve captured so well in this regard in Bottomland is the tension between the Hess family and their neighbors. Can you talk about the link between conflict and language?

I’m a sentence hound. I admit it. If a book has bad sentences, I can’t read it, no matter how supposedly gripping the plot. I’ll leave it up to readers to tell me if this attention does or doesn’t follow through in creating good sentences of my own.

But yes, in some frightening ways, the central conflict of the book can be very much linked to language. With Harding’s Babel proclamation, widows were arrested in cemeteries if overheard speaking to their dead in anything other than English. Others were caught speaking German over party lines. Books were burned, the names of streets changed, the names of food, and of whole families. The United States has never had an official language, despite some attempts at forgetfulness to argue otherwise. And yet, the idea of “American” has often, by some, been equated to English, no matter what.

But this kind of silencing happens between my characters as well. Midwesterners, or at least the kind I grew up with, weren’t the most emotive or talkative bunch. My characters aren’t either (though I use Patricia, who marries into the family, to act as a kind of comic relief to this reticence). Their language has to disguise a lot but also brim with subtext so the reader can understand what is really being said and how. And of course, the choice of five different narrators, though it caused plenty of headaches, gave me the chance to play with rhythms and sentence structures that I otherwise wouldn’t have. Writing in third person sometimes allows an author to stay closer to her stylistic comfort zone. I couldn’t do that. And I think it helped me, overall, as a writer.

As someone who has built a cult following as an instructor, how does teaching inform your work now versus earlier in your career?

Teaching is my release. It’s the reason I can look myself in the mirror. It’s difficult, of course. It takes a lot of time. And I don’t always get it right. I’ve had a lot of 3am insomnia bouts when that happens. Some writers consider what they do to be a kind of contribution to their community, to the higher arts, the desire to transcend, to literature as a whole. Of course, many writers and their books are. I always hope my own books give readers a certain beauty and complication of experience, a step outside themselves that has some worth, some truth. But I’d never want to assume that what I write actually has that power. I can hope for it. I struggle for it. But I can’t sit on my laurels and think the job is done. So I have to do something else to keep me from feeling too self-important.

There’s really nothing like seeing that glow when one of your students holds her published book (or two, or more) for the first time. I’m not being altruistic here. I get too much out of it. I don’t have children. I never really wanted them. But I think I understand a very small part of what parents must feel. Something I’ve done is continuing, even if it’s continuing only by way of a word, a sentence, an idea. I’m proud of my own work, certainly. But I’m equally proud of theirs. The process, when it works, makes them so down-out happy. I want to buy them drinks and cake. I want everyone to.

Which fiction writers do you return to year in and year out for inspiration?

There are the writers who I consider “rural writers,” who are attacking settings and lifestyles that I’m attracted to myself: Kent Haruf, Annie Proulx, Marilynne Robinson, Louise Erdrich. There are other writer’s writers like these, the ones whose sentences are like whole milk: Alice McDermott, Charles Baxter, Elizabeth Strout. Finally, the writers who take chances, who keep my head spinning for possibilities of my own: Dan Chaon, Kate Atkinson, Jim Crace, Emily St. John Mandel, Justin Cronin…. I could go on and on. There’s so much good work out there. I don’t have time to read it all, let alone return to the ones that speak to me most.

Where do you want to take your fiction from here?

When I tell people about the book I’m working on now, they usually say: Wow. That’s really different. It is and it isn’t. But I’d like to keep stretching my limbs in terms of settings, characters, time periods, and styles. I like to take on ideas that seem a little bit impossible. There’s where I get my writing energy. If I didn’t do that, I might have a couple more books out.

Can’t I be more specific? Well, I guess you’ll have to wait to see what happens next.

2 comments