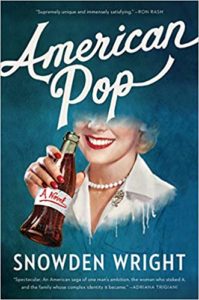

Snowden Wright’s new novel, American Pop, is just out (William Morrow, 2019) and already it is being called spectacular and lauded as a smart and tragic exploration of American history. It is a multigenerational tale of a family that builds a soda pop empire from a Mississippi Delta drugstore, chronicling their epic rise and catastrophic fall. And while most sweeping sagas of this ilk focus on glamour, or at least devote a good chunk of the narrative to it, Wright looks at the family from the underbelly. He focuses on the rough flaws and ugly intricacies barely giving readers a glimpse of any polish and that is what makes this book unforgettable. It is, after all, the secrets that we crave – not the gloss.

Snowden Wright’s new novel, American Pop, is just out (William Morrow, 2019) and already it is being called spectacular and lauded as a smart and tragic exploration of American history. It is a multigenerational tale of a family that builds a soda pop empire from a Mississippi Delta drugstore, chronicling their epic rise and catastrophic fall. And while most sweeping sagas of this ilk focus on glamour, or at least devote a good chunk of the narrative to it, Wright looks at the family from the underbelly. He focuses on the rough flaws and ugly intricacies barely giving readers a glimpse of any polish and that is what makes this book unforgettable. It is, after all, the secrets that we crave – not the gloss.

Aside from smart prose and a captivating story, what really drew me in was the unorthodox, nonchronological leaps Wright makes between characters and chapters. Wright dangles just enough information for readers to puzzle together sordid and delicious details; and once I made out the whole, this style made me feel smarter than I am – and far more invested in the Forster family. It was brilliant. If you loved Ethan Canin’s America, America (Random House, 2009) as much as me, then you will love American Pop. Now, let’s get to the good stuff.

I’m dying to know about the unorthodox structure, your nonchronological leaps. How did you do it? Did you use an outline?

While writing the novel, I naively thought the nonlinear chronology was no big deal. I thought, Well, of course this is the way it has be. Everybody will see that. Cut to now, years later, and it’s the element of the book I’m most frequently asked about. What an idiot I was!

Every writer manipulates time. Chronology in any novel, linear or nonlinear, is artifice. In a linear novel, writers elide time, with hours, days, weeks, months, or years being skipped over between chapter breaks, and writers dilate time, with one tiny moment, just a second, taking place over a twenty-page chapter. So with American Pop I leaned in to the artifice of chronology, and in that way, I hope, I was able to make it more artful.

I didn’t use an outline. At first, the order of the chapters was instinctual, but during edits and rewrites it was more intellectual. I thought a great deal about the friction I wanted to create in the juxtaposition of scenes, characters, time periods, and settings. Kind of like a mixed tape.

And why did you choose to barely let us see any of the glamour in the Forster’s lives?

Drama feeds on conflict. Readers aren’t interested in happy families. They’re interested in unhappy ones.

Actually, until you mentioned it, I didn’t realize that the moments of conflict in the novel so outweighed the moments of glamour. I supposed that’s my instinct as a storyteller. Years ago, while on book tour in my home state, I drove with my father to a reading in Greenwood, Mississippi. I told him how I like to start each reading with an anecdote that relates to the town or area. “For this one,” I said. “I’m going to tell that story about your father, how he grew up in Greenwood and every year won the newspaper’s contest for who could bring in the first bloomed cotton boll of the season. What nobody knew was that he’d built a small greenhouse, where each year he grew a single cotton plant.”

My father cocked his head. “That’s funny, but it’s not true. Your grandfather won the contest each year, but he didn’t cheat.”

I gradually realized that, over the years since I’d first heard the story as a child, my subconscious had fictionalized the truth. I’d made a fact not only more interesting but also more believable by turning it into a lie. I’d made it a better story by adding secrets and deceit, those unglamorous, morally complicated parts of life.

Sticking with this theme, most of the Forsters were haunted by their past. Whether it was poor decisions or poor luck each had something that weighed them down. Did you ever consider letting one of your characters escape the family curse?

Think about Southern literature. The most common trait in Southern literature is a reckoning with the past, a coping with our history of slavery and racism. Our past is constantly bubbling up into our present. With American Pop I tried to mirror that element. The South is saturated with the past, present, and future, all at once. Just like a family. Just like America. One thing, minor or major, has ripple effects.

If I let a character off the hook, I’d have to let the entire South, the entire country, off the hook. I will say, though, that one character does escape the family curse, but to add more would be a spoiler. That character represents hope for the future.

Our readers LOVE this one. What was the biggest editorial change you made while editing American Pop?

I was first drawn to my editor not because she thought the book was great but because she thought it could be better. The main thing she wanted was more interiority for the characters. After a long phone call, she sent me off for six months to work on the novel. I spent that time combing through it and exploring the characters’ thought and feelings, digging deeper into their psyches, letting the reader get to know them better.

During those six months I added roughly ten-thousand words to the novel. I didn’t add any new scenes. I only added interiority. Creating all of those new thoughts and feelings was difficult, sure, but it was even more difficult to fit them into the narrative so they felt organic to it. I took it as a huge compliment that my editor couldn’t pinpoint which sections were new.

Moving along, you wrote, “ ‘Just people trying to live.’ That was what Ramsey’s father used to say, fancying himself a philosopher, when he looked at a candid public scene or was feeling particularly sentimental.” I couldn’t help but think this was the antithesis of the Forster family philosophy. Was anyone in the Forster family just trying to live? Why or why not?

Good point: That does sound like the opposite of what would hypothetically appear on the Forster family crest. They aren’t just people trying to live. They’re people trying to succeed. The Forsters embody the American Dream. Perhaps that’s part of why Ramsey’s father thinks of those words. The more people who are just trying to live, the easier it is for people like him to succeed.

Of all the Forsters, I’d say Harold, quiet, gentle, dogged by a mental disability, most embodies that phrase. Because of his disability, he can only watch, tragically, as his siblings, nieces, and nephews destroy themselves in their own tragic ways. Harold considers himself the protector of the Forsters. Ultimately, however, he ends up their institutional memory, keeper of a museum dedicated to the Panola Cola Company and the family, his family, that owned it.

This passage was closely followed by another one of my favorites, “Ramsey didn’t have to be herself. She could be a reflection of a reflection of herself. She could be a trick of the light.” What were you thinking when you wrote this?

I’m so glad you liked that part, because it’s some of the new interiority I mentioned in a previous answer. That scene takes place immediately after Ramsey undergoes a traumatic event in New York City. She’s sitting in a coffee shop, coping with what she’s just been through. With that passage, I tried understand her thoughts and feelings in that amount, and I decided she would deal with the trauma via the mechanism of narrative, by making herself a character. People who question the validity, power, or usefulness of storytelling are often, shocker of shockers, terrible at telling stories. Ramsey’s a good storyteller.

Finally, let’s get personal. What are you reading now? What books do you recommend?

Right now I’m ankle-, waist-, neck-deep in research for my next novel, which concerns the Confederados, roughly 20,000 Southerners who, after the Civil War, immigrated to Brazil. They were enticed by cheap land, tax subsidies, subsidized travel, and the fact that slavery was still legal there.

The research for this sort of project is potentially endless. I have to research not only the Confederados but also the Civil War and Brazil. The Civil War alone is the subject of countless, often-multi-volume texts, so I’m sticking with what’s arguably the best single-volume text: James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. So far it’s fantastic. For research on Brazil, I’m excited to read a LIFE World Library book written by Elizabeth Bishop. Yes, the Elizabeth Bishop. Can you imagine?

About Snowden Wright: Snowden Wright, born and raised in Mississippi, is the author of the novel American Pop, chosen as an Okra Pick by the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance and for the “Discover Great New Writers” program by Barnes & Noble. A graduate of Dartmouth College and Columbia University and a former Stone Court Writer-in-Residence, he has written for The Atlantic, Salon, Esquire, The Millions, and the New York Daily News, among other publications, and previously worked as a fiction reader at The New Yorker, Esquire, and The Paris Review. Wright was awarded a Tennessee Williams Scholarship to the 2018 Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and his debut novel, Play Pretty Blues, was the recipient of the 2012 Summer Literary Seminars’ Graywolf Prize. He lives in Atlanta, Georgia.