Life Magazine 1966

Some writers keep returning to the story they have to tell until they get it right.

When I started my YA novel Half in Love with Death (Merit Press – December 2015), I’d already abandoned two novels about a young girl who falls in love with a man who may be a murderer. This story drew me irresistibly, but every time I tried to write it I got stuck in the middle.

My third novel would have ended up in a drawer with the others if it weren’t for my sister. When I told her I was struggling with my plot, she suggested I base it on a true crime, and not just any true crime. She confided in me that when she was twelve, she’d been obsessed with the disturbing case of Charles Schmid, ‘the Pied Piper of Tucson.’

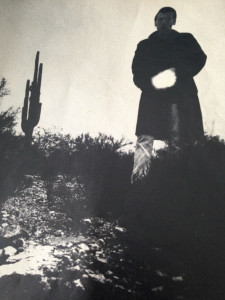

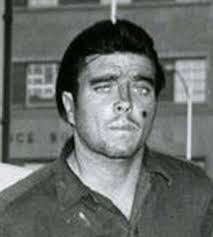

Charles Schmid Life Magazine 1966

In 1964, Schmid, known as Smitty to his friends, killed Aileen Rowe, 15, and buried her in the desert. A year later he killed 17-year-old Gretchen Fritz (his girlfriend), and her sister Wendy, 13. But Schmid wasn’t your classic loner serial killer. In spite of the fake mole he painted on his cheek and the tin cans he stuffed in his boots to appear taller, teenage girls adored him. A Life Magazine article from 1966 featured haunting black and white photos of a sullen young man with “mean, beautiful” eyes. His friends followed him like he was a ‘pied piper’ because, as they told the magazine, he wasn’t “boring.” And when he bragged about the murders, his followers kept his secret.

I could understand why this case transfixed my sister. It wasn’t just the details of the murder, grisly though they were (Smitty and his friends lured Aileen into the desert just to see what it felt like to kill someone, and the Fritz sisters’ bodies were left to rot in the sand). It was that the teens pictured on those pages looked a lot like kids we knew. If something so horrible could be concealed behind such a normal facade, how could you trust anyone?

Despite my sister’s fascination, the case hadn’t been on my radar as a teenager. I was too preoccupied with my patchouli-scented crowd of unconventional friends to follow the story of a far-away serial killer. As an adult, though, I wondered if the feelings that drew Tucson teens to Smitty weren’t all that different from those ‘magical’ feelings of connection that drew me to my friends in the Sixties. I decided to step through the small dark door my sister had opened with her suggestion.

Much has been written about the case, including Don Moser’s excellent The Pied Piper of Tucson and Joyce Carol Oates’ iconic short story “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” Smitty himself was pretty loquacious; he captivated his friends with musings on the importance of living in the moment and made statements like, “If I’m imperfect it’s because He made me imperfect, so therefore God can’t blame me for anything I do.”1

Smitty wasn’t just a philosopher, either. He was also a liar. He lied to manipulate the many girls who were in love with him. He lied about himself, claiming, among other things, that he was dying from Leukemia. He lied about the murders. Smitty lied so much that it was hard to determine what really happened, let alone distill it into a novel. But the high level facts of the case gave me a roadmap for my story. I might choose to veer away from the reality of what happened, but at least now I had some idea where I was going.

The case also provided me with a setting. I was nervous about moving my novel from Boston to Tucson, but this unfamiliar location freed me from the inhibitions of autobiography. Places like Speedway, the sleazy strip that Smitty and his friends cruised, and the desert where they drank, partied, and buried the dead, became unexpected sources of inspiration in the fictional world I was creating.

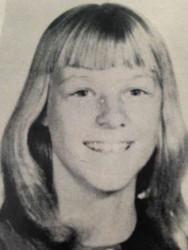

Wendy Fritz Life Magazine 1966

As to be expected, there isn’t much information on Smitty’s victims. I found a little on Aileen and Gretchen, but almost nothing on Wendy. One of her few mentions was in the Life article, when Smitty is quoted as saying that after he strangled her sister, Wendy kept going, “huh, huh, huh.” I doubt those were actually her last words. He was a liar. Regardless, that is not the way a 13-year-old girl should be immortalized.

The photo of Wendy in Life, with her uneven bangs and trusting smile, reminded me of myself as a young teen. She seems blissfully unaware of what is coming next, much as I didn’t foresee the impending tsunami that was the Sixties, until I was drowning in my illusions of love and enlightenment. But unlike me, Wendy was not granted the luxury of hindsight and regret. Though I know very little about the real Wendy Fritz, her story touched me, and helped me to find the voice I used for Caroline, my novel’s protagonist.

True crime fascinates many of us — as evidenced by the popularity of The Jinx and Serial — but there are challenges to turning the myriad facts of a case into a good story. As the Guardian recently wrote in reference to the genre, “Any true crime story is shaped by what is included – or, more pertinently, left out.” I had to put many details of the crime aside so that my novel could emerge. Half in Love with Death ended up being very different from the case that inspired it. But the Pied Piper of Tucson gave me a much needed framework for my plot and characters, and led me to the story I needed to tell.

1Gilmore, John. Cold-Blooded: The saga of Charles Schmid the notorious “Pied piper of Tucson”. Portland,OR. Feral House. 1996

5 comments