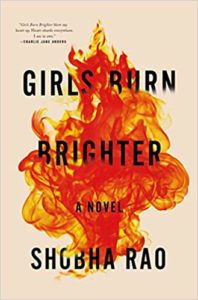

Shobha Rao’s stunning novel, Girls Burn Brighter, is just out in paperback (Flatiron, 2018) and you should run, not walk, to your local bookstore and buy a copy. It was named one of the best books of 2018 by NPR and The Washington Post and it was a finalist for a Goodreads Choice Award. Incandescent and electrifying are two of the words often used to describe this novel and I couldn’t agree more. Set in modern day India, the novel traces the lives of two girls, Poornima and Savitha, caught in the undertow of poverty and family expectations. They weave saris together and dream of escaping the expectations of marriage and motherhood but are ripped apart by devastating acts of cruelty when one is assaulted and the other is sold into a loveless, abusive marriage. Once separated, a long list of seemingly simple choices add up to enormous blunders that leave both girls as slaves. I say they made seemingly simple choices, but did they have choices? That’s what lingers, what stayed with me long after I put this book down.

Shobha Rao’s stunning novel, Girls Burn Brighter, is just out in paperback (Flatiron, 2018) and you should run, not walk, to your local bookstore and buy a copy. It was named one of the best books of 2018 by NPR and The Washington Post and it was a finalist for a Goodreads Choice Award. Incandescent and electrifying are two of the words often used to describe this novel and I couldn’t agree more. Set in modern day India, the novel traces the lives of two girls, Poornima and Savitha, caught in the undertow of poverty and family expectations. They weave saris together and dream of escaping the expectations of marriage and motherhood but are ripped apart by devastating acts of cruelty when one is assaulted and the other is sold into a loveless, abusive marriage. Once separated, a long list of seemingly simple choices add up to enormous blunders that leave both girls as slaves. I say they made seemingly simple choices, but did they have choices? That’s what lingers, what stayed with me long after I put this book down.

Read this book because it is a beautiful, brutal story that reveals the truth about human trafficking, both the humanity of its victims and the gore inflicted on them–but read it too because it is a love story and a testament to the human will to survive, to the beautiful ambition these girls hold that even after all they’ve endured they can still find a better future. We at Dead Darlings were thrilled when Shobha agreed to this interview, so let’s get to the good stuff:

Most of our readers are writers—and we want to know: Shobha, you worked on this book for fifteen years. During that time were you constantly re-writing pages? Or did you produce pages and outlines slowly? How did this novel come together?

The true answer is that I wrote Girls Burn Brighter in two months. It was an act of maniacal devotion, without night or day; Savitha and Poornima deserved nothing less. But what I did do for fifteen years is learn how to write. During those years, I practiced the craft of writing. The discipline of it. Because that, too, deserves great devotion. One that is ongoing. And requires only ink and blood and courage. In the end, those fifteen years are what made those two months possible.

Writing Girls Burn Brighter had to be an act of love – love for the characters, for their story. How much did you write from what you knew v. from research? And what parts were the most personal and/or the hardest to convey?

I’ve had a lifelong preoccupation with the lives of women. How they are conducted, how they are controlled, how they dwell in known and unknown powers. I also worked for many years with survivors of domestic violence, and the stories that these women (and nearly all of them were women) told me were astonishing. Each day in these women’s life – marked as they were by continual acts of violence – was a testament to the human will to endure, and to our unimaginable capacities for resilience, reinvention, and generosity. I didn’t have to look much beyond these everyday survivors to understand the lives of my characters. As for what was most personal: all of it! I want to believe that Poornima and Savitha, no matter what they went through, felt me beside them. Because I certainly – during the writing, and even today – feel them beside me.

They are poor. They are ambitious. They are girls. Those are the three descriptors you seem to use most when you talk about Girls Burn Brighter. What came first, the novel or these descriptors? Why?

The novel most definitely came first. And then, once written, it was a matter a distilling the biggest forces working against Poornima and Savitha. Gender and poverty – there is no end to how deeply and disturbingly these two elements alone determine the fate of a life. They determine opportunity, education, marital choice, reproductive choice, resources, lifespan, living conditions, medical, governmental, and institutional access, access to clean water, air, housing, and whether a woman will have enough food, enough choice, enough freedom, enough of everything. And then when you add ambition to this mix, this cocktail of deprivation, then you have a kind of symmetry. Then you have a story.

Quick follow up, what surprised you the most as you created Poornima and Savitha?

Their friendship surprised me. Although I had set out to write the story of two friends, I had no idea of the depth of that friendship. I had no idea they would come to rely upon each other so beautifully, so utterly. They shared even their strength, even the last few droplets of their strength, across continents, across time, across ravages. I was left in awe. I might’ve created them, but they taught me what it means to be a friend.

Our readers LOVE this one. What was the biggest editorial change you made while editing Girls Burn Brighter?

I was writing Savitha and Poornima’s stories straight through, and I realized that that was inadequate for telling the truth of their journeys. So I went back and alternated sections, so that the novel jumped between their points of view. That felt more kinetic. And I think it keeps the reader from becoming comfortable, complacent. These are girls in constant, unrelenting danger, fighting for their lives, their bodies. If the reader stops to check their phone, then I will have failed them.

Moving along to content. Mohan is perhaps the only male character in the book who shows a side that isn’t cruel. I almost felt bad for him. What were you thinking about as you created him? What purpose did you want him to serve?

I wanted to show that great cruelty can coexist with great love. And that it often does. Most everyone in Poornima’s and Savitha’s lives were driven by profit, the sale of girls, and that dictated their role in the novel. But Mohan was driven by something different, by something more beautiful, and so he stopped to look. He stopped to consider. And that contemplation–as contemplation often does–led to great revelation, great disorder, and great rupture.

You wrote, “The world is full of middlemen.” Can you tell us what you meant by that and how that idea shaped your novel?

I wanted to confront this notion that there are some people in the world who are bad, and the rest of us are good. That is untrue. We are all complicit. How is it possible to drive along the interstates in the middle of America–as I was doing–and see billboards indicating what signs to look for when encountering a possible victim of human trafficking? At gas stations and rest stops, the billboards read. These places are where the girls–and yes, a majority of them are girls–are often bought and sold and transferred and trafficked. The very same gas stations and rest stops that we frequent, oblivious, living our lives, refusing to see. How are we not complicit? When it is happening in our midst? The bodies of girls are for sale. In your backyard and in mine. It must stop, and until it does, we are all made into middlemen.

Finally, let’s get personal. What are you reading now? What books do you recommend?

When I am preparing to write (as I am now), I read reams and reams of poetry. Only poetry. I pick it up wherever I can–on the subway, snippets on a telephone pole, graffiti on a sidewalk, the side of a building. I also seek it out, work from poets such as Angel Nafis, Franz Wright, Danez Smith, Ross Gay, Philip Levine, Emily Dickinson, Tongo Eisen-Martin…it is insatiable, this need in me for poetry. It makes me brave; it makes my heart swell with love for words, for their utterance.

About Shobha Rao: Shobha Rao moved to the United States from India at the age of seven. She is the winner of the Katherine Anne Porter Prize in Fiction, and her story “Kavitha and Mustafa” was chosen by T.C. Boyle for inclusion in Best American Short Stories in 2015. She is the author of the short story collection, An Unrestored Woman. A resident of San Francisco, Girls Burn Brighter is her debut novel.