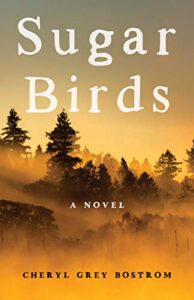

Cheryl Bostrom’s SUGAR BIRDS is an immersive exploration of loss, redemption, and coming of age in the breathtaking Pacific Northwest wilderness. After accidentally setting a tragic fire, ten-year-old Aggie runs to the woods her father taught her to navigate, where she remains hidden with the trees and birds she loves so much. Teenage Celia, new to town, quickly becomes involved in the search party seeking out Aggie. Reminiscent of Kristin Hannah’s The Great Alone, SUGAR BIRDS is a powerful tale of survival, community, and growing up in the harsh beauty of the natural world.

Cheryl Bostrom’s SUGAR BIRDS is an immersive exploration of loss, redemption, and coming of age in the breathtaking Pacific Northwest wilderness. After accidentally setting a tragic fire, ten-year-old Aggie runs to the woods her father taught her to navigate, where she remains hidden with the trees and birds she loves so much. Teenage Celia, new to town, quickly becomes involved in the search party seeking out Aggie. Reminiscent of Kristin Hannah’s The Great Alone, SUGAR BIRDS is a powerful tale of survival, community, and growing up in the harsh beauty of the natural world.

Your novel started with only three key words calling to you: trees, a young girl, a fire. Can you talk more about the genesis of your novel, and the role the subsequent writing workshop you took had on the formation of the novel?

Trees. Girl. Fire. They all showed up in a sketch I wrote for an online Gotham Writing Workshop, the first piece of fiction I’d ever submitted to peers for critique. Two things happened after I turned it in. First, young Aggie began to stalk me—whistling at me from trees along the creek near our home. Crying from shadows beyond a campfire’s reach. Hounding me at 3 am until I threw off my covers and took notes. Second, fellow workshop writers liked the sketch. Really liked it. Urged me to write the whole story. Some even wrote me privately about its potential. I have to say that their encouragement awakened in me the possibility that this concept could become long-form fiction, and inspired me to develop it.

Sugar Birds is told from alternating points of view. One is ten-year-old Aggie, who is the girl with the fire. The second is teenaged Celia, who has recently moved in with her grandmother in the town Aggie lives in. When Aggie goes missing, Celia and the town are determined to find her. Can you talk about your decision to make these two characters your points of view, and what you felt each brought to the narrative? Were there ever any other POV characters that you debated on telling?

When Aggie’s campfire goes rogue and burns down her home, she watches firefighters haul her parents from the flames before she hides in the woods. At ten years old, she’s a preadolescent child, and her guilt and sorrow are pure and devastating. Untainted by adulthood’s rationalizations, her resulting shame drives her not only into the woods, but into emotional and spiritual wilderness, where she struggles to interpret her suffering and forgive herself. Since she’s solitary through most of the story, and because her grief and skewed worldview are internal, she had to be a POV character if readers were to encounter and consider her pain—and her growth through it.

Originally, I thought Aggie’s would be the only POV, but too much subplot was lining up among those who were searching for her. Readers also needed someone to balance Aggie’s delusions, and since Aggie’s narrator couldn’t leave the frightened girl, I began looking for another POV. Loomis, Nora, and Mender had already solidified on the page, but their voices were wrong for the position, and Burnaby didn’t become fully dimensional until a few drafts in. Celia flew in from Houston in tight-lipped third person, so at first she wasn’t right either. But when I rewrote her in first person, the girl began interpreting the various hungers in the story, including her own, and became my second POV character.

Because of their ages, both characters are at very unique places in their development. Aggie is still a child, but thanks to her father, incredibly knowledgeable about nature and how to survive in it. Similarly, Celia is a mix of anger and hormones that she has to reckon with for the course of the novel. How did you approach characterizing these two protagonists, and balancing the interplay between wisdom and naivete on the page?

They both had to live in my head and on random legal pads until I knew them—their cognition and motivations; their personalities, loves, and longings; their fears and mood swings. To do so, I drummed up both rich and difficult memories from my own childhood growing up on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula; recalled beautiful instruction about nature that I absorbed from my grandparents there (and that I have studied ever since); tapped my ongoing fascination with birds. I reminisced with my sister about ways we escaped some pretty hard stuff as we roamed (and climbed trees) in PNW forests, and we remembered how the natural world comforted us. I also spent time with our spunky, practical ten-year-old neighbor girl, picking her brain. I re-entered my own tumultuous teen years, as well as those of many high school girls I later taught and mentored. Since I always watch relationship dynamics—especially father-daughter and mother-daughter ones—I called on ways children change as they mature, and how kids react when adults fail them and when they don’t . . . and when the kids themselves fail. I considered how faith, or lack of it, shapes hope.

All of the above fed Celia and Aggie. As they acted on the resulting thoughts and emotions, I injected piecemeal arrivals of wisdom and courage and compassion that shaped their arcs.

Your characters go through so much struggle and pain, both emotionally and physically. Writers always talk about how you need to have permission to hurt your characters. Was it difficult putting your characters through the events in the novel, and how did you go about amping up the struggle as you wrote?

Difficult to turn those screws? Without question. Things were bad enough with Bree’s illness and Wyatt’s deception. But once I sent Aggie to the laundry room for matches, her decisions set in motion events that grew progressively worse. I wept with all my characters as I wrote their suffering. However . . . because hope is foundational to my worldview, and because I have personally endured trauma and emerged with resilience and a greater capacity for joy, I trusted my characters could, too. I knew their pain wouldn’t be their whole story.

My favorite question to ask authors on Dead Darlings is, did you personally have any darlings you had to cut? What is your favorite scene that didn’t make it into the final novel, and why did you cut it?

Well . . . yeah. Icy, I know . . . but Granddad Burke, and a tender scene of him and Celia in the barn workshop, had to go. He was amazing and wonderful and wise and all that good stuff, but had he lived, he would have steered the story in a mawkish direction and filled a heart void necessary for Celia to strike out on her own. Besides, once he was gone, Burnaby had room for all his skeletons. I didn’t mourn his passing.

Are there any other books brewing now that Sugar Birds is completed? Any new set of key words calling out to you?

Yes! A sequel, decades later. Keywords: furrow, Burnaby, inscription. Another character-driven, suspense and theme-rich love story set in the remote, dramatic Palouse. The protagonists are hogging my blankets.

Cheryl Grey Bostrom is a naturalist, photographer, and award-winning writer. She has previously authored two nonfiction books. SUGAR BIRDS, releasing on August 3, 2021, is her first novel.