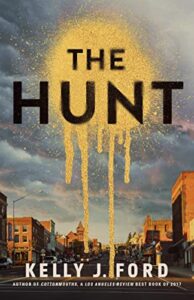

In the Arkansas of Kelly J. Ford’s third novel, The Hunt, Easter season does not mean pink bows and bunnies. It means bored or needy townspeople seeking a golden egg and prize money. Gossips and greedy sponsors seeking social currency and sales. Zealous Christians seeking recruits and redemption. Most of all, it means a disappearance and, usually, a death. Is there a seasonal serial killer on the loose? Will this year produce another victim?

In the Arkansas of Kelly J. Ford’s third novel, The Hunt, Easter season does not mean pink bows and bunnies. It means bored or needy townspeople seeking a golden egg and prize money. Gossips and greedy sponsors seeking social currency and sales. Zealous Christians seeking recruits and redemption. Most of all, it means a disappearance and, usually, a death. Is there a seasonal serial killer on the loose? Will this year produce another victim?

Called “a modern master of the rural noir” and celebrated by Best Thriller Books for her “ability to draw readers into the chaos and craziness of everyday life while exploring themes of shared trauma, family dynamics, and the societal constraints of small-town America,” Kelly J. Ford has written her most multi-dimensional novel yet, introducing us to a compelling cast of characters whose humanity matters as much as their survival. What a treat to Zoom with her and learn about her fascinations, frustrations, and factory jobs on the way to her latest success.

The Hunt is populated with seekers, and you turn your readers into seekers, too. We must figure out what’s going on in Presley. How much were you a seeker as you wrote the story? Did you know where it was headed?

Whenever I’m writing, I’m always seeking because I never know the end. I feel like every draft, I’m just seeking the story. I have been using a lot of power tools lately that are breaking, and I have to take them apart. I’m like, “Well, you don’t know how to fix it until you take it apart.” So I try to apply that to revision. I’ll start a draft, and then I’ll go back through, and I’ll read it. And I’m like, “You know, this isn’t working. I need to fix this.” And so I kind of tear apart my drafts as I go. I might find something more interesting in a later draft and change my idea of what the ending is. The endings are so hard to land. You want something that’s resonant.

Did you know if there was going to be a hunter?

I didn’t. I’m one of those readers who likes things a little bit ambiguous. I’m very much like a townsperson in the hunt: What is going on? Who is behind all of this? I start with this cast of characters, and I know how each of them ticks. For every single character, it’s like, What do they want? What is their obstacle? What are they going to do to get it? Once you have those kind of built-in engines, you can just let your plot go. And then it’s kind of fun. You go into that wonderful, trance-like state, and you start to figure it out, and then it’s almost like, “Oh, my God! That’s what happened!”

How did you determine the size of your character cast? Since everybody you introduce is a potential suspect or victim, I wondered if you felt your cast would get out of hand or if you felt, “No, it has to be this big.”

This book is kind of the culmination of two other books that I trunked. I already had some characters that I really loved. I took two main characters that already existed from those books and put them into this book. And somehow, it worked. I knew I wanted Nell, and I knew I wanted Elijah, and they seemed like a perfect fit together: aunt and nephew bound by this circumstance of Elijah’s father going missing, and then his subsequent death, which many in town attribute to a serial killer. And when there’s a serial killer, you kind of don’t have a choice but to have a lot of characters. Inevitably, you have a giant cast.

But I also really love Jami Attenberg’s The Middlesteins. I love that book, and I was always like, “I would love to have a book that has all these characters and be able to see if I can do it.” The world of Cottonmouths, my debut, was so small—very few characters, very claustrophobic—and so it felt like a pressure cooker. And then Real Bad Things was, again, not a ton of characters. So in a way, I just wanted to have fun and expand my cast. Then by nature of choosing Elijah… well, Elijah is 17 years old, so that [determined] a lot of the plotting. And not even plotting. More like logistics. Between me and my editor and my copy editor and the proofreader, we’re all like, “Wait a minute, what year is it?” We had all these lists written down, like, this is the year that this person died, and how they died…

Why was Elijah so pivotal? It sounds as though you built your whole timeframe around him.

Yeah, I just wanted to focus on the individuals impacted by these deaths. You know, thinking about things like true crime—the spectacle of true crime, but also the fascination with it—I mean, I’ll read a lot of that, but there is something icky about it at times. There are real people behind it. Elijah is pivotal in that it’s his father, it’s a loss, he never knew him, and there’s this entire event in town where everyone’s in a frenzy. And his father is the rumored first victim. That to me is so compelling, putting yourself into a person’s shoes. Our characters are people. They’re not just characters; they’re individuals that we live with for a long time. What must it be like for someone who has this hole in their heart? What must that feel like, especially when you never got to know them as a person and you can’t truly move on? Because there’s not real closure. I’m always fascinated by that angle of a crime. I’m just always fascinated with psychology. There are a lot of really excellent books that go into victim stories. So I wanted to bring that into it.

For the most part, the novel tracks Nell and Ada using close third-person narration. Why did you decide to center both women’s experiences?

They present two sides of the town. One side is like, “This hunt should not happen, even if there’s not a serial killer. There are deaths associated with it every year.” And this side is convinced it’s because of the hunt, serial killer or not. Nell, whose brother was affected, is more toward this side. But then on the other side, you’ve got people like Ada, who is an avid Egghead, someone who loves the hunt, who is more logical, thinking, “Of course people are going to get hurt. Nobody’s doing anything, and then suddenly everyone goes out and is active in the community, looking around, not paying attention, so you know, of course accidents happen.” I just wanted to have that closeness for both sides. I also wanted to present a different perspective on these working-class women in Arkansas. You don’t see that all the time, especially in Southern fiction, where the working class is often typical cisgender white males; they’re the ones working at the factories and having a hard time. So then it’s like, I’ve worked in a factory, two factories in college.

What did you do?

Oh, my gosh. So the first one, you know microwave screens, the little holes? I used to work on the line that took those off the line after they were painted. You had to use these very heavy gloves because they were so hot. And we would take them off the line, and at the end of our shift, we’d have to take paper clips and poke through the holes if they were painted over.

Sounds like a really creative job for you.

I know, I kind of loved it. And then the one I worked at the longest, the factory that the one in the book is based on, it was a plastics factory. I was like [the character] Marcy, the white bumbling label operator. And then I got to move up to press operator, like Ada. So I’m very familiar with both their jobs, and it was just fun. I’ve always wanted to use that experience in a book because you just don’t read about it that often. It’s a fascinating setting because it’s dark, it’s at night, it’s in the middle of the woods, it’s very loud. So you can’t really hear anything but white noise. It has this creepiness to it that I love.

Outside of those two points of view, you’ve interspersed shared Google doc entries, text exchanges, tweets, Facebook posts, and news reports. What was your thinking behind including those? Why that structure?

Anytime I’m writing about a small town, there’s that claustrophobic, insular thing. But when it comes to an event, it wouldn’t make sense to me, it wouldn’t be as interesting, to just tell a story straight, like water-cooler talk. I don’t like it on TV or in books when someone says, “Well, so-and-so said this, and this, and this.” It feels like feeding information to the audience. It’s just not that dynamic. So with the interludes from the townspeople, I’ve got this kind of Greek chorus, little snippets of their perspective. It gives you a more well-rounded view of what it’s like in the town, what people are thinking and saying. And it gives you different demographics as well. It’s more storytelling, as opposed to writing. It’s way more fun. I [also] work a full-time day job in technology, and I don’t see anyone all day long. I’m always in Google, Google docs. I’m always on Slack and sending messages. I’m always texting. So [with] electronic communication —and the news, you know, news reports, Facebook, that sort of thing, Twitter— I’m just filling out the world.

I’ve been thinking about the rate of revelation and how, in a good novel, the writer is constantly negotiating the questions she raises and the pace at which she answers them, if she answers them. Big questions obviously drive the plot (Whodunnit? Whodoinit?), and similar questions drive whole sections of the book (Where is Elijah? Will Ada and Nell get together?). But there are also more immediate scene-powering questions (Who or what made that noise?) and more overarching philosophical questions (Can love conquer loss?). I’m curious how consciously you managed all these question layers. What was your approach in creating the novel’s tension and momentum?

I’m not the intellectual writer who thinks about all these things as I go along. I wish I could say I was. At the end of the day, I’m just trying to tell a good story. I’m not thinking about those little pieces. I’m literally just telling myself a story as I go, like, I’m my first reader. I also spend a ton of time daydreaming. In my head I’m editing, so by the time I put it on the page, it’s in pretty good shape. In many ways, it’s just based on intuition. Also reading across genre, outside of my own lane, is very helpful.

What are you reading outside your own lane?

Right now? Well, it’s still in my lane. I’m reading Megan Abbott’s Beware the Woman, which is amazing. I love her work. I want to be slotted next to her in terms of style because it’s a slow burn, and I love a slow burn. I want to take my time with sentences. I will read a page-turner, but for me, there’s nothing as satisfying as when you really get to appreciate the sentences and the tone and the atmosphere that a writer creates.

Years ago you said you were drawn to “the intoxicating stew of shame, sexuality, Christianity, and crime.” Definitely those are in this novel, too, but so are guilt and abandonment and problematic or useless authority figures. What ideas powered this third novel, especially compared to your first two?

I definitely didn’t start with theme. I think theme belongs to the reader. Because often I’m like, “Oh, I didn’t know that! That sounds cool.”

If any part of the novel did not survive, why did you kill it?

I cut about 50% to 75% of this. I was talking with my beta reader, and she was just like, “This feels like two different books.” And she was right. And so I was looking at it, and I was like, “Okay, so, I’ve got to take out this book…” Luckily, that can be another book, right? So nothing is wasted. I use everything. But yeah, I had to rewrite everything new kind of late in the process. But it was fine because it worked out. I feel like I have a better book for it.

In a 2017 interview for Cottonmouths, you said you’d love to see LGBTQ literature evolve to include more than the hurt, but first the rest of the world has to do its part in making a safe space for it. How do you think LGBTQ literature has evolved since then?

There are definitely more books out there. There’s more awareness. There are more editors who are taking a chance on books by LGBTQ writers. Not all. We still hear things like, “I don’t know who this book would appeal to,” or “I’m not sure how wide a market there is for this.” I mean, all you have to do is open up Twitter to see that it’s not a great time for queer people. So there are always barriers. But a lot of queer people have come together. I can truly only talk about the crime fiction community, but I’m involved with the Queer Crime Writers group, and they’ve been instrumental. It’s wonderful as a writer to find people who you don’t have to explain anything to. Part of it is just finding your people and then supporting each other. Part of it is you don’t care anymore. If a straight person doesn’t get it, who cares? If you don’t want to read it, don’t read it.

I really liked how you handled your characters. Because they’re all just people in the world, you know? The conflict in a novel with LGBTQ characters doesn’t always have to relate to identity politics. Just let me know them, and tell me a story.

Yeah. And that’s what’s the most fun to do here. With this book, the characters are not struggling with their identity, but they’re struggling with a circumstance that puts them in a harrowing situation. And they just happen to be gay. But it’s also a critical piece of their identity because you just have a different lens when you’re not the same as everyone else.

You’ve been navigating the publishing industry a while now. What have been your highs and lows?

A high is right now. Writing can be heartbreaking and so beautiful and joyous. Publishing is primarily heartbreaking. Because it’s just a difficult industry. There are only so many editors. There’s only so much money that gets spread around to various authors. And so you’re shooting for the lottery. And it’s so tied to your identity, speaking of identity, that it’s crushing if you get a rejection. But I love where I’m at now. I love being a mid-career author, not because I’m so celebrated—most people have no idea who I am—but because I like being a part of a writer community that’s at the same level. It’s really fun. It’s nice to not feel that desperation.

When you’re an aspiring writer, you just have to live through it. It feels sometimes like there’s nothing that anyone, especially an established writer or a published writer, can tell you that can make you feel better. You’re just kind of like, “Well, that’s easy for you to say. You’re published.” Not feeling that anxiety anymore feels like such a gift. It took so much hard work to get there. But I’m grateful to be there, not because I have great success or anything, but because, you know, I’m just another writer out there doing my thing.

If The Hunt is your last book, will you be satisfied?

Absolutely. Because when I write now, I feel that confidence and that comfort. I can just relax, and I feel like that shows in the writing. I feel like it’s expansive, and it can breathe a little bit. And that’s so much nicer than just agonizing over every sentence. Yeah, it’s more fun now. It’s a lot more fun now.

Kelly J. Ford is the Anthony-nominated author of Real Bad Things; Cottonmouths, a Los Angeles Review Best Book of 2017; and The Hunt. Kelly writes crime fiction set in the Ozarks and Arkansas River Valley. Find out more at kellyjford.com, on Twitter, and on Instagram.