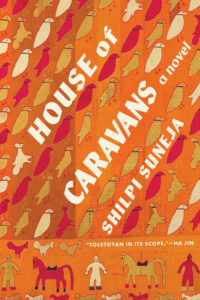

One family burdened with division over three generations. Shilpi Suneja‘s debut novel, House of Caravans (September 2023, Milkweed Editions), chronicles the birth of Pakistan and an independent India with grace, scrutiny, and depth. Somehow, she manages this saga in just over 300 pages – her skillful prose does not shy away from the physical or emotional violence of Partition or its continued aftershocks.

One family burdened with division over three generations. Shilpi Suneja‘s debut novel, House of Caravans (September 2023, Milkweed Editions), chronicles the birth of Pakistan and an independent India with grace, scrutiny, and depth. Somehow, she manages this saga in just over 300 pages – her skillful prose does not shy away from the physical or emotional violence of Partition or its continued aftershocks.

My favorite moments of this novel come in the embraces – between siblings, neighbors, mother and children. Through moments of gentle wholeness, Shilpi hints at whether there’s peace available beyond political and religious difference.

I could gush about this novel and Shilpi all day. Of course, I’m not alone: Kirkus Reviews called House of Caravans “reminiscent of Zadie Smith’s White Teeth… a moving evocation of life before, during and after, Partition and the past’s immeasurable impact on the present.” Shilpi holds two MFAs from Boston University and UMass Boston, is a NEA and MCC fellow, and is a GrubStreet Novel Incubator graduate. So, let’s get on to hearing directly from the author.

Your novel shows us India at two different time periods – with a divided family and the immediate and then ongoing impact of The Partition at the center of this story. What drew you to this story of two sets of siblings?

Possibly because I’m an only child, I find sibling relations fascinating. Biology and/or family tie you together, and for that reason, you feel compelled to chart out your own course in life, disagree with the older sibling or disapprove of the younger one. I tapped into these notions to construct the characters of the two brothers. Similarly for the sister and brother, these relationships have both love and hate built into them, so it was fascinating to explore something as eternally volatile as Partition dividing siblings and families apart. The different time periods allowed me to explore how relationships evolve: how we build each other up and how we tear each other down because we disagree politically, or because we make the same mistakes and can see ourselves reflected in the other. There’s nothing more infuriating than watching a younger sibling or cousin make the same mistakes as you and acting completely naïve about it.

Is there a character you feel closest to? I’m curious how you approach building character and who was easiest and who was hardest for you to relate to.

I think all of the characters have a little bit of me in them. I think tapping into one of your own vices or preoccupations gives you interesting possibilities for your characters. It definitely helps you to get to know them better. As for easy and hard, there are a lot of minor characters in this book, so some were easier to write than others. The main characters take up a lot of space, as they should. It requires a delicate balance to make the side characters perform their role and not have them be too memorable or too forgettable. The side characters help in creating atmosphere and conveying the politics and culture of the time.

Other writers will want to know how were you able to tackle an epic like this in under 320 pages. Your style is so rich and descriptive, and the story spans generations – you pack so much into each page. What is your writing and editing process like?

I did not want this book to end up being 1,000 pages or even 500 pages. Were it that long, it would have taken a lot longer to edit and would have been a totally different book. From the very beginning, I wanted to convey heft and evolution with as much economy as possible. I tried to capture entire relationships in one or two scenes, in gestures, in objects. It was important to me to capture as much time as possible in as few pages as possible. The editing process was long and repetitive, and I would write scenes only to take them out, leaving only a whisper of a detail from all the research. By the time I found my editor, the book was quite tight, and he helped me to identify places where I could slow down. I was very grateful for that breathing room.

Grubstreet’s Novel Incubator is just one of several writing programs you have completed. In fact you have several degrees and are working on your PhD in Literature now, and also teach. Any advice or takeaways about participating in and running writing workshops for other novelists?

The last two versions of the book were written outside workshops, so even though I have gone through a lot of school and the stellar Novel Incubator program (Michelle Hoover is just the best and most generous teacher and writer!) I had to turn inward and write from what I had internalized. If you’re working on your own, you definitely need someone to keep you accountable. I exchanged my manuscript with one other writer, because without deadlines it is very hard to finish anything. My advice is to find one or two accountability buddies with whom you can exchange your manuscript and give them what you’re seeking for your book.

Your novel has many heartbreaking poignant moments because of the family division that comes from religious difference and intolerance. It’s a stunning book to read at any time, but particularly right now. What if anything from today’s politically divisive moment influenced your writing this?

There is division everywhere you look. The very concept of a nation implies division–there are borders, boundaries, armies. Even within nations, there is discord. Every time the elections roll around people talk about leaving the union–Massachusetts being on its own, California being on its own. I remember these conversations from 2016 and 2020–family members fighting over politics. The issues in contention aren’t trivial at all–immigration, climate change etc.– but the elevated levels of partisanship creates an emotional civil war. I tapped into this heartbreak while writing the book. I wanted to explore, especially with the ending, if after a lifetime of resentment and bitterness, a compromise could be reached, long overlooked wounds redressed, conversations started.

Several of your characters are surrounded by books and poetry at various points. Other times they have to leave books behind. I love that you threaded a love of reading throughout your novel. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading books that have been on my reading list for a while and with whose authors I will soon be in conversation: Rishi Reddi’s Passage West, Daphne Kalotay’s The Archivists, Rajiv Mohabir’s Whale Aria and Antiman and Shubha Sunder’s Boomtown Girl. Also, Jen Soriano’s Nervous, which is such a beautiful and necessary book.

I got to read an early draft of this novel in 2014 so I know it’s been through many edits since then. What’s your advice or any lessons learned through the editing and publication process?

The writing and editing process is full of paradoxes–you have to hold on to your original vision, but you also have to let your project evolve and take you to new places. You have to spend enough time on it, sometimes daily, but you also need to take long periods of break so you can return to the pages with fresh eyes. As long as you are learning and surprising yourself, I say keep going!

Shilpi Suneja was born in Kanpur, India, an industrial town with a dark colonial past, four hours southeast of New Delhi. At the age of fifteen, she moved with her parents to a tiny village in North Carolina. Her short fiction and essays, nominated for a Pushcart Prize, appear in Arrowsmith, Asia Literary Review, Bat City Review, Cognoscenti, Consequence, Guernica, Hyphen, Kartika Review, Kafila, Little Fiction, McSweeney’s, Michigan Quarterly Review, Solstice, Stirring Lit, and TwoCircles.Net among other places. Her first novel, House of Caravans, is based on her grandfather’s story of migration from Lahore to Kanpur.

For more conversation with Shilpi and the first pages of her novel, listen to a recent episode of The 7AM Novelist Podcast.

1 comment