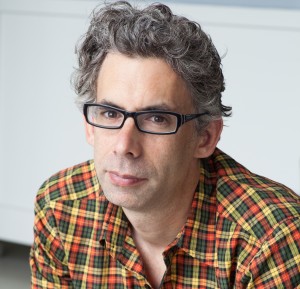

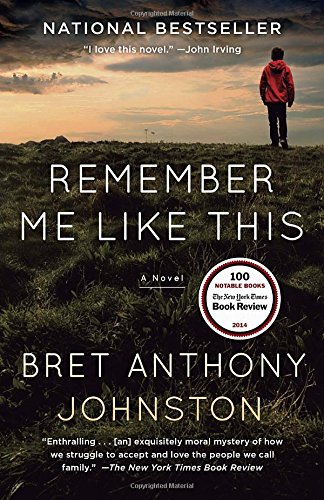

Building on his critically acclaimed short story collection, Corpus Christi, Bret Anthony Johnston’s debut novel “Remember Me Like This” traces the emotional progress of the Campbell family following a teenage son’s reappearance four years after an abduction. Bret took time out from his teaching – he directs the creative writing program at Harvard – to speak with Dead Darlings about his new release.

Building on his critically acclaimed short story collection, Corpus Christi, Bret Anthony Johnston’s debut novel “Remember Me Like This” traces the emotional progress of the Campbell family following a teenage son’s reappearance four years after an abduction. Bret took time out from his teaching – he directs the creative writing program at Harvard – to speak with Dead Darlings about his new release.

Dead Darlings: What drew you to this material?

Bret Anthony Johnston: In a word, the characters. As a writer, I’m endlessly fascinated by where we take shelter and what happens when those shelters collapse around us, when they become prisons of a sort. In one way or another, all of the characters in the novel are saddled with that burden, and it wasn’t long after I started writing that I understood the depths and complexities of their struggling.

The book, though, started very small. For years, almost decades, I’d been wondering who would volunteer for those brutal overnight shifts with a dolphin. I’d done some volunteer work like that before I left Texas, and I’d always heard that the overnight shifts were impossible to fill. And yet, when I looked on the schedule, those slots were never empty. So I started imagining who the volunteer was. I knew there would be some kind of insomnia would be involved, but not what caused it, so I wondered what was keeping the volunteer awake. I wondered why not volunteer during the day, and it occurred to me that the person wanted some kind of anonymity, that she was hiding in her way or at least hoping not to be recognized. This went on for years, this accrual of her character. I’d started thinking of her as a mother, and I imagined her bringing in an inflatable alligator, just an old toy from her garage, to cheer up the dolphin. Such a gesture, such maternal compassion, made sense to me. Then I started to think about the breath inside the blow-up alligator, and I realized that it would have been her son’s, not hers. That’s when everything clicked—years and years after I’d volunteered—and I realized that what was keeping her awake was that her son had gone missing. I understood that she volunteered in hopes of saving the dolphin because she felt she’d failed to save her son. Once I knew those things, then the book laid itself out in front of me. Her loss and longing were the keys that opened up the door to the novel.

DD: The topic of your novel seems drawn from the headlines, yet the book focuses more on relationships than plot. Can you describe how the structure emerged, and what changes in form may have occurred during the revision process?

BAJ: I always knew there would be multiple points-of-view. I knew that my curiosity toward the characters was that expansive, but beyond that, the structure emerged with each draft of the novel. I had no idea that the book would span a summer, and I had no idea that it would culminate the way it does. In fact, I was writing toward a different ending. I expected the book to end at a different time, in a different place, with a completely different set of events drawing the narrative to a close. About halfway through, however, I recognized that I was imposing my will on the story, forcing it toward an ending that made sense for me, the writer, as opposed to one that made sense for the characters. From there, I surrendered the ending to them and I followed their lead. The ending now is infinitely superior, and it was as much a surprise to me as I hope it will be for the readers.

As for revision, the biggest change that my peerless editor Kendra Harpster suggested was to cut a part of the structure. When I sent her the finished manuscript, there were a number of very short, somewhat mysterious first-person chapters braided into the narrative. The reader couldn’t tell who was writing them until the end of the book, and I really liked them. I thought they were adding to the mystery, but Kendra said they were doing the opposite, slowing down the reader and dispelling the tension. Immediately, I knew she was right and I cut them. The book is infinitely better for her many suggestions throughout the time we worked together, and certainly better for having me tighten the story in that way. She did what the best editors do: she worked to make the book the ideal version of itself. I’m beyond grateful.

DD: You have a remarkable talent for slowing down moments through sensory description, thought, and action. One example early in the book is Griff sweeping out the empty swimming pool where he likes to skateboard, and worrying about his girlfriend Fiona. Can you talk about how you approach these moments, and how you go about exploring them fully?

DD: You have a remarkable talent for slowing down moments through sensory description, thought, and action. One example early in the book is Griff sweeping out the empty swimming pool where he likes to skateboard, and worrying about his girlfriend Fiona. Can you talk about how you approach these moments, and how you go about exploring them fully?

BAJ: Thanks for these kind words. And you’re absolutely right that I’m trying to slow down the narrative in those moments. Sometimes it’s simply a pacing decision, and others it’s an issue of allowing the character’s thoughts or emotions or memories to breathe. Like so much in my writing, these things often come down to empathy. The goal is to render a character’s consciousness with authenticity, nuance, and breadth, so I cleave to those moments where their heads and hearts feel especially rich, especially active.

In the scene you mention, I wanted to delve into Griff’s thinking for a specific reason: he’s worried Fiona won’t show up and I wanted the reader to wait with him, to worry with him. Revealing what was going on in his mind allowed me to lengthen that moment and perhaps raise doubts in the reader’s mind about whether Fiona would stand him up. Everything I do, every tool I use in a scene, feels designed to collapse distance between the reader and character. Despite everything that’s going on in Griff’s family’s life and with his brother, he is also a fourteen-year-old boy with his first girlfriend and I wanted to respect that. I wanted to show the extent to which he could still experience that part of his life and the extent to which he couldn’t. His thoughts are trained on Fiona, he’s overly concerned with how he’ll appear to her if she arrives, but thoughts of Justin and his broken parents flare up without warning. All of this feels important for the reader to experience upon first spending time with Griff.

DD: Your ability to collapse distance between reader and character induces a lot of empathy once Griff’s brother Justin returns. We’re rooting for the parents, Eric and Laura, to hold things together long enough for the family to reunite. One character who plays a stabilizing role is Eric’s cantankerous father Cecil. Can you discuss how Cecil emerged, and whether his role may have evolved during revision?

BAJ: Because of my history with skateboarding, most people assume the character I identify with most completely is Griff, but really it’s Cecil. This news was as much as surprise to me as it is to people who are kind enough to read the book and ask me about it. What it says about me that I identify with a 67-year-old pawnbroker with a felony gambling conviction and an unregistered pistol in his truck, I don’t know. But it’s true. Of everyone in the book, his character feels closest to my own.

And yet he surprised me at almost every turn in the book. Without giving too much away, I can say that in my original conception of the novel and Cecil’s character, I thought he would play a more significant role in the story’s conclusion. I think it’s fair to say that he thought he would too. That we were both surprised at the way the book evolved felt promising to me. His evolution away from my original intention seemed a good indication that the reader would be surprised, too.

In early drafts of the book, Cecil was more belligerent. He was unforgiving, aggressively so, and the effect was too threatening, too unlikeable. To my mind, he felt a little too macho. A little too vigilante-ish. Those qualities are still there, the reader certainly sees glimpses of them in small and large ways throughout the book, but I didn’t believe that Cecil would broadcast them so blatantly. He’s a man who keeps his cards close to his vest, and in the early drafts of the book, his cards were face-up on the table in every scene. Much of the work that I did with him was the labor of restraint, of toning him down. To do this, I kept returning to the fundamentals of characterization, asking myself again and again what Cecil wanted and how he would go about trying to get it. He’s a man who takes the long view, but the earlier version of his character was rash and short-sighted. It took draft after draft, year after year, to make those changes.

DD: Your strong identification with tough-talking, gun-toting Cecil reminds me that most of your published corpus (pardon the pun) is set in South Texas, whereas the corporeal Bret is a creative writing professor in Massachusetts. Can you describe what it’s like to commute mentally from Cambridge to Corpus Christi every day of your writing life?

BAJ: Well, during the winter, it’s actually quite nice weather-wise. I don’t find it difficult at all, which has as much to do with my having grown up in the area as it does that I tend to do a lot of research when I visit Texas now. I can’t remember a trip I’ve taken down there that hasn’t resulted in boxes of local newspapers, books on the flora and fauna, maps and such being shipped back. I take a lot of pictures when I’m down there and I go on long drives where I try to get lost. If I stay in a hotel that still has a phonebook in the nightstand–most don’t anymore–I steal it. A lot of writers do their research on the Internet, and I’ve done some of that, but I’d rather have a box of paper to rifle through.

And it’s also true that I see the landscape more clearly from this perspective, from so far away. The contrasts shine light on where the stories are hiding. The longer I’m away from Texas, the more my curiosity grows. The distance is an invitation and a mandate to write fiction that matters. I cast off far more ideas than I ever commit to the page, every writer does, and the decision to write often comes down to whether I can imagine the action of the story taking place anywhere else. If I can, I tend to let the idea go. If it’s something that can only happen in a landscape that intrigues me, then I start writing.

DD: Some of the most difficult material relating to Justin’s abduction occurs off-stage, and is left to the reader’s imagination. The situation is complicated further because we don’t hear from Justin’s point-of-view. One exception is a disclosure between Officer Trevino and Paul Perez at the aquarium two-thirds of the way through the book, which deepens our understanding of what actually happened. Can you talk about how you approached the “rate of revelation” in this novel?

BAJ: I really like your phrase “rate of revelation” and having it articulated that way, I can recognize how important it is to me. For the years that I was writing the novel, I had an enormous bulletin board in my office, and in addition to color-coding the POVs for each character, I had a running list of what the reader had seen and heard in each chapter of the novel. For example, I knew when each character first encountered the postcard, and I knew what Justin had shared as well as what information about Justin the family members had gathered on their own. My goal was always to allow enough time to pass for the reader to feel the full impact of the revelation. If it happened too quickly, then the impact would lack the surprise that the revelation deserved. If the revelation happened too late, I risked the reader having forgotten important pieces of information and thus the revelation being dampened, muted.

With Justin’s abuse, I wanted the reader to feel the same anxiety that the rest of the Campbells do. I had no interest in using his abuse as a kind of revelation that would reward or punish the reader, but rather, the question of what and how he suffered should feel omnipresent and inescapable. Which is, I feel sure, how the abuse felt for him. By the end, if I’ve done my job, you’re wondering not how he suffered, but how he survived. You’re wondering less about his abuse and more about his strength.

DD: Speaking of anxiety, during the latter half of the book an unseen menace blankets the Campbell family’s consciousness as completely as the persistent heat wave that has settled over Corpus Christi. Can you describe how you managed the tension level, section by section, at an appropriate level?

BAJ: So much of my writing comes down to inhabiting a character’s POV in a deep and authentic way. The whole business of perspective really fascinates me, and I think the trick to inhabiting a character’s consciousness comes down to understand their obsessions. Our brains have evolved in a way that we can really only process one thing at a time, so I try to find out what that thing is for my characters, what is amplified and magnified in their experience to the degree that it mutes and eclipses everything else. Once I find that out, then I mine that obsession for everything I can. I try to see the world as the character would, so if the characters are afraid of something the reader should be too.

Another thing I tend to do is try to imagine the worst thing that could happen to a character, given what I know about him or her. That is, I stay away from broad and universal fears such as sickness and heartbreak and death, but I look for what would be particularly difficult for this character. With the Campbells, after their son is home, there’s only a few things that could happen that would continue to frighten them after they’ve been through so much. I tried to make sure those things happened in believable ways. It’s all in service of understanding the characters better, in inviting the reader to participate in their experiences. Show me what a person is afraid of, and I think I know who that person is. Show me what a person is afraid of, and I’ll show you a story waiting to be written. Each section of the novel felt like a story of a particular fear, and the goal was for each section to build on what had come before.

DD: One of my favorite chapters in your non-fiction book on craft, “Naming the World,” talks about the necessity of building flaws into characters in order to make them sympathetic. Can you pick a character from “Remember Me Like This” and talk about the choices you made in endowing him or her with a key flaw?

BAJ: All of the characters in the book seem flawed to me. They feel vulnerable, wounded. As a writer, I try to find out where my characters are wounded, and once I do, I stick my finger in the wound and pull until I find out how they react. I did that exercise with each one of the main characters, and many of the minor characters as well. Something I tell my students is to find out where their characters are broken, where they’re vulnerable, where they’re weak. Do that, and you’ll find the heart of their stories.

And that’s what I’ve tried to do with each character in the novel. For example, with Eric, he’s having an affair and he’s worried that he’s a coward. Both of these things determine some of his most significant actions in the book, and they permeate his consciousness. He’s also someone who has real trouble moving beyond the past, beyond what Justin has endured. All of these things weigh on him, isolate him, compromise him. They were a way to force pressure upon him and see how he’d react. I have no interest whatsoever in judging my characters. Beyond almost anything else, I think judging your characters, even the most vile among them, is the worst thing a writer can do. So, despite Eric or the others behaving in ways that some folks might find reprehensible, all I wanted to do was understand his actions and see where they led him. I wanted to corner him with every flaw I could imagine and see how he got out, if he got out. It’s what I try to do with all of my characters.

DD: Your calm, meticulous prose pulls us closer to the characters without drawing attention to itself. Here, for example, is an excerpt from Cecil’s point-of-view early in the book. “The feeling he had was one of false calm, a fleeting sense of lassitude. It was like the eye of a hurricane. The last four years had been the first wall and soon, after this current stillness collapsed, they’d get hit with the storm’s second, harsher side. The dirty wall, it was called. The one that uprooted trees and twisted off roofs and turned cement foundations to mud.” Purely from the standpoint of language – words and sentences – which writers do you turn to, year in and year out, for inspiration?

BAJ: It’s difficult, if not impossible, for me to distinguish language from story, from character, from plot and perspective. If the language is lackluster, let alone unclear or ambiguous, I can’t concentrate on the story. I don’t say this in a judgmental way at all, but rather something of a shortcoming on my part: I focus too much on the language and it prevents me from enjoying what might otherwise be a really compelling story.

Writers that I’ve recently read whose language I love include Paul Yoon, Alice Munro, Cormac McCarthy, Jorie Graham, David Wojahn, Ann Patchett, Elizabeth McCracken, Michael Ondaatje, Denis Johnson, Laura van den Berg and Amy Hempel. The novel STONER by John Williams is a really interesting case study in terms of language. The prose is relatively plain, relatively commonplace, and yet the sentences move and flow and linger like nothing I’ve ever read. There’s nothing ornate in the language, nothing conspicuous in terms of length, meaning it’s neither minimalist nor lush, but the reader just feels borne along by the pages, enveloped by the way he renders the world. I’ve talked with many smart people about this, and I can’t figure out how he did it. I’m reminded of looking through a perfectly clean window, one where the glass is so invisible that you forget it’s there and you only focus on what’s on the other side. That feels like the goal to me. The language is the tool through which we experience the story, but the tool must never draw attention to itself. The beauty is in its invisibility, its ability to evoke the image without the reader understanding how the image was so perfectly evoked. Faulkner, of course, said that the explosion must occur in silence. I think about this a lot when I’m revising sentences.

DD: As an educator, someone who has stewarded a creative writing program for many years, I’m curious whether you’ve noticed any shifts in concerns and sensibilities among your students, and whether those shifts have influenced your own work?

BAJ: There may be something of a trend toward writing Young Adult books, but I don’t see it as pervasive or malignant. It was either Bellow or Henry James (depending on whom you ask) who said that every writer is a reader moved to emulation, so if students are cutting their literary teeth on YA books, then it follows that they would have an interest in writing those books. I feel pretty sanguine about it. In the same way that a reader’s taste matures, so will the writer’s interests. And it’s really possible that some of the students will go on to write a wonderful YA book that will inspire other readers and writers. It’s more than possible, in fact, and who could argue against extending an invitation to future readers and writers. I’m just glad that the trend is no longer veering toward irony and cleverness. Those things worried me.

But, no, the shifts or trends haven’t influenced my work. I’m sure Random House wishes otherwise. I’m sure an awesome YA novel about vampires or survival games would sell a lot better than a book about a kidnapped kid and a sick dolphin.

DD: Fiction writing and skateboarding. Compare and contrast.

BAJ: The similarities are endless in my mind, but so as not to bore our beloved GrubStreet readers to death, I’ll just focus on the idea of repetition. Learning how to skate or learning a new trick comes down to trying the same thing again and again and again. I’m talking about hours, weeks, months, sometimes years. You have to put in the time, often without any kind of encouragement or reason to believe you can pull off what you’re trying. Still, you log the hours. You obsess over this thing you’re trying to do. You try new angles, new techniques, then when those fail, you start over. Repeat, repeat, repeat. This has been a part of my life for almost thirty years, and it’s conditioned me as a writer. I don’t expect anything about writing to come easily or quickly, and I really do think that comes from what I’ve experienced with skating. I’ve known other writers who feel the same way about tennis, wrestling, their time in the military or music conservatories. We’ve been groomed to focus on the process, to embrace the repetition, to get up early and do the drills. With skating, though, when it doesn’t work you’re sliding across the ramp on your face. With writing, you just hit delete. That’s an easier day at the office.

DD: What’s next?

BAJ: I’m close to finishing a second collection of stories and I’ve got an idea going for the next novel. I’m also interested in doing some more work in film and possibly television and of course teaching. I’m also going to be really cranky if I don’t learn a few new skateboarding tricks by the end of the year. I’m close on a couple of them, closer than I’ve ever been, so I just need to make time to do the work.

1 comment