During this pandemic, I have traveled, with nary a mask in sight, to the Highlands of Scotland, an island in Tahiti and, most recently, a mountainside village in Jamaica. Tamp down that frisson of anger you feel—I’m speaking, of course, of traveling through reading. In these monotonous days of danger, I have never felt more grateful for novels.

During this pandemic, I have traveled, with nary a mask in sight, to the Highlands of Scotland, an island in Tahiti and, most recently, a mountainside village in Jamaica. Tamp down that frisson of anger you feel—I’m speaking, of course, of traveling through reading. In these monotonous days of danger, I have never felt more grateful for novels.

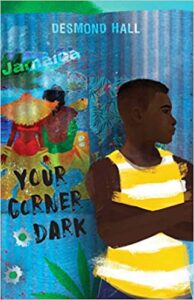

And so, I read Desmond Hall’s debut novel Your Corner Dark with wonder, tears and gratitude for the chance to gain an understanding of a side of Jamaica that I might never see otherwise. Far beyond the beautiful waterfalls and beaches, the fancy resorts, and the airbrushed tourist world, lives Frankie, a young man in a small mountainside village, who has worked his entire life to earn a coveted engineering scholarship to America. A small act of defiance alters the course of his life and forces Frankie into an unbearable situation in which he must give up his dreams and join his uncle’s gang in order to save his father’s life. It is a stunning coming-of-age story about impossible choices, the dark deeds and small graces of gang life, and the lengths we will go to save someone we love—and ourselves.

ECS: Desmond, thank you so much for talking with me—I absolutely loved this book. I always want to know the origin story of a novel—what was the seed from which this beautiful novel grew?

DH: My uncle was murdered in a gang-related incident. This caused a lot of trauma in my family, especially between my mom and I. We didn’t resolve the issue before she died, so writing YCD was cheaper than therapy.

I’m sorry about your uncle. Unresolved trauma is at the heart of this book, especially with Frankie and his father, Samson, who have a complicated and tough relationship, made worse by the loss of Frankie’s mom. This was never more clear than in the scene where Frankie gets the scholarship. There is so much pain and misunderstanding at work in that scene – can you tell me more about it? Because it sets up the scene for later when we all are screaming at Frankie to listen to his dad and NOT go to Joe’s party but, like any kid, he thinks his dad is out of touch, small and backward. And that misunderstanding combined with Frankie’s desire to be free has life-altering consequences.

Wow, it’s hard to say it any better than you did. Father and son relationships always seem to be filled with pain and misunderstanding. In the scene with the scholarship, the loss of Frankie’s mom comes into play. She was the “glue” of the family, and such a strong presence in the memories of both Samson and Frankie. So, I used her death, or the commemorating of it to drive a wedge between father and son, or I should say drive it deeper. (I love the writing technique where we try to figure out how the best thing can become the worst thing)

Your dialogue is always on fire – and I especially love how you fit idioms into dialogue without it feeling forced. How do you approach dialogue in your writing?

Thanks for saying that! I eavesdrop, and imitate. And I think it’s appropriate to name drop right now. I remember talking to the great screenwriter, Budd Schulburg. I asked him how he came up with that great line from the awesome movie, ON THE WATERFRONT. “…I coulda been a contender…instead of a bum.” He said he was in Gleason’s boxing gym and overheard a palooka saying those words to his manager. Mr. Schulburg said he quickly jotted down the line because he knew he would use it in a script one day.

I sort of do what he did but I also try to keep the cadence and attitude in mind when I imagine what else that character might say.

You do a wonderful job of dropping us into the setting of Frankie’s Jamaica – the water pump, the village, the party, Frankie’s bus ride to the hospital; the hospital itself; and then Leah’s house on the fancy side and the market. Reading this book felt like going on a trip to Jamaica, but seeing the full reality of it, not just the tourist airbrushed version. Tell me about setting and what you want people to take away about Jamaica after reading Your Corner Dark?

Like most Jamaican ex-pats, I love “yard.” We wish the economic situation were different, but wishing doesn’t make it so. Still, I would love it if readers gathered that Jamaica is not a ____hole country. The complexities of International finance, politics, bad luck, and an overall lack of opportunity can make us all become desperate. “If not by the grace of God there I go.”

When Frankie finally acquiesces to his uncle and joins the posse, after fighting so hard against it for so long, my heart broke. Everyone in this book is so fundamentally human–so flawed and broken—that they can’t help themselves. How does such a flawed, broken, sensitive soul like Frankie’s come to terms with the awful things he has to do? And how did you find a balance in the writing of the book where, despite those awful things, he never veered into an unlikeable character?

I think Frankie is a bit like Michael Corleone in the Godfather movie. He didn’t want any of this, but he has a family to look out for. That’s a very relatable plight, one that leads us to wonder what we might have done if we were in his shoes. It also makes us glad that we don’t have to walk his walk, but it’s dang interesting to read about.

The word “Bumboclot” appears a lot in the book and seems to have many meanings. Can you tell me about it?

It’s a curse word that is ubiquitous. It’s sometimes referred to as Bomboclaat, and it’s usually spoken to express anger. “Bumboclot, the Jets lost again!”

Whether or not he leaves, Frankie is already of Troy but not in it. He has a wider lens on Jamaica, sometimes to his benefit and sometimes to his detriment. I’m thinking about the moment when he looks at his posse members holding a duct-taped rival member who has just killed a friend and imagines “a macabre postcard: ‘Greetings from Troy. Wish you were here.’” Can you say more about his unique perspective of straddling two worlds, unlike everyone else in the book?

Every once in a while I read about valedictorian-type-students who come from the so-called “ghetto.” They have that unique viewpoint that you mention. In Frankie’s case, he knows poverty, gang life, as well as AP Calculus, but because he doesn’t have upper middle class life experience he can be flummoxed by sushi.

Frankie drops in and out of patois seamlessly throughout the book. As you wrote the book, how did you think about patois and how/when to include it?

The reception I got on my first draft was priceless, maybe even painful. My beta readers had quizzical looks on their faces, wondering whether or not to tell me they didn’t understand what was going on. They wanted to be polite, which was understandable. But after having in depth conversations with those readers the truth came out. It turned out the level of patois (patwah in Jamaica) was a problem. Even referencing the patwah as patwah was confusing to them. They knew the reference as patois. Of course, every Caribbean reader would understand patwah, and even get a warm “back home” feeling from it, but those readers weren’t Caribbean. So, I had to go through dozens of iterations, and lots of trial-and error to find the proper amount of Jamaicaness. If I were writing specifically for Caribbean readers the balance would be different.

Aunt Jenny, man. She is a force. I would read a whole other book about her. Can you talk about the inspiration for her character and what role she plays in the book?

Jamaican women are strong!

Earlier in the book, you write, “She also hadn’t told him that he would begin to see the world differently from them. The more he had learned, the more he had drifted, like his genes had transformed. His education had given him some sort of strength, but it was also a weight, a pressure he had to carry that the others didn’t. Things were expected of him now.” Your Corner Dark is a powerful addition to the bildungsroman literary tradition, as we watch Frankie grow through his formative years, and see him grapple with the weight of education and the weight of home. Can you say more about how education changes Frankie? I don’t want to give any spoilers, but do you imagine him achieving his educational goals at the book’s end?

Frankie, of course, is enlightened by education. It also gives him opportunities that life might not have offered if he hadn’t hit the books. But education also separated him from the other boys on the mountain. His worldview became larger while theirs stagnated. They didn’t embrace education, consequently they didn’t evolve through learning like Frankie had. Frankie noticed the results of becoming different from his friends, particularly in the way they quickly embraced the gang life because they didn’t have other avenues to pursue “success.”

As for your second question, I can’t give anything away about the ending, or my beloved editor will get me.

Desmond Hall was born in Jamaica, West Indies, and moved to Jamaica, Queens. He has worked as a high school biology and English teacher in East New York, Brooklyn; counseled teenage ex-cons after their release from Rikers Island; and served as Spike Lee’s creative director at Spike DDB. Desmond has served on the board of the Partnership for Drug-Free Kids and the Advertising Council and judged the One Show, the American Advertising Awards, and the NYC Downtown Short Film Festival. He’s also been named one of Variety magazine’s Top 50 Creatives to Watch. Desmond lives outside of Boston with his wife and two daughters.

1 comment