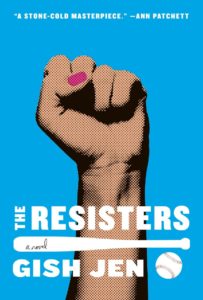

Picture a dystopian America divided into two classes, mostly submerged underwater, lorded over by the internet that’s half surveillance and half-AI. The haves are the ‘netted’ who are ‘angelfair’, and live on high dry ground, and have jobs. The have-nots are the ‘surplus’ who are ‘coppertoned’, jobless and exist to consume. This is the setting for Gish Jen’s The Resisters, a sharp take on modern ills with a deeply hopeful emotional core.

Picture a dystopian America divided into two classes, mostly submerged underwater, lorded over by the internet that’s half surveillance and half-AI. The haves are the ‘netted’ who are ‘angelfair’, and live on high dry ground, and have jobs. The have-nots are the ‘surplus’ who are ‘coppertoned’, jobless and exist to consume. This is the setting for Gish Jen’s The Resisters, a sharp take on modern ills with a deeply hopeful emotional core.

Gwen, the protagonist, is a gifted baseball pitcher born into a surplus family. Ultimately, she must choose between joining the elite by modifying her body with technology or resisting and staying true to her surplus roots. Through baseball, knitting, and AI, Jen unpacks identity, discrimination, and what it means to be human.

It’s fitting that I speak to Jen during a dystopian day: just after Massachusetts has declared a state of emergency due to coronavirus. Characteristically, Jen is realistic yet upbeat. She’s listening to Seamus Heaney’s The Cure from Troy, when I call and immediately emails over a link. “You’ll feel better,” she promises—and I do. If The Resisters sounds uncomfortably like a probable future, it is also at heart, an ode to the beauty of humanity that will make you feel better.

The Resisters is set in a dystopia, which is a departure from your previous work. What made you choose a dystopia?

The book picks. I did not pick it; it picked me. In this case my daughter had just gone off to college. For the first time in about 30 years, I didn’t have to worry about getting dinner on the table or getting a kid through the college application process. I was able to sit down and let it come.

I’d just told my daughter have fun, explore, take risks, so I let myself do that. In this very open frame of mind I started writing. Now that the book is done, I can see that it was a kind of nightmare I was having because I had this daughter going out into the world, and when I looked at this world there was a lot to be concerned about.

That’s why you see the climate change, the concern for future democracy, the concern for future technology, and the hope, and that’s why you see the knitting—months after the women’s march—and you see the idea that a sporting event could be a site of resistance because of Colin Kaepernick.

It’s funny because I can see where the baseball might have come from, but I don’t know why I started writing about baseball. I don’t play baseball, my daughter definitely doesn’t, so I didn’t have to worry that I was impinging upon her and her privacy.

What was the process of putting together this world like? How conscious were you of elements like world-building and seeding just enough information about the world so readers could understand it?

It’s funny because I’ve never done something like this. I’d never even heard the term world-building until I was done. I’m working in a much more intuitive way. I’m making the world up as I go, I know the things that make me laugh, or I can feel my stomach tightening.

It’s like getting a plane up into the air. I’m much more interested in can I get it into the air and can I get it back down? Things like will the [reader] be able to figure out what this is, that comes much later. That’s the point where it’s what’s the logo on the tail of your airplane.

The most important thing is where’s the heartbeat—that kind of question is much more what’s on my mind.

How was the writing process for this book different or similar to your process for other books?

When I started writing, I did short stories, so I learned to write by having an impulse and following it out. Because it’s the only way I really knew how to write, when I sat down to write my first book, I did it the same. Every week I would go to some reading and a famous writer would be up there and say if you want to write a novel it’s probably good to have a plan. I’d go home and be like, I don’t have a plan. You’d think that I would have learned from that and now I’d have a plan, but I never did learn to work that way.

What is true is that if something is not working, I will go back and plot it. So, if I’m 150 pages in and I’ve lost the heartbeat. It’s not writing itself and I don’t know why. At that point the analytics might come out. I’ll plot it and take a look at it and say oh, I see, I went wrong here. There was a lot of conflict, but here the conflict shifted, I started writing about something else, or I lost my nerve, or I got distracted.

I wrote this book very quickly, but typically it takes four to five years to write a novel. You can’t stay with a project for four to five years because you have decided to answer some question like how can I motivate people to think in a more progressive fashion? Maybe other people can…but not for me. It has to be something that’s much deeper, much more subconscious, that’s really quite important to me. I’m not taking something and dressing it up for the public, I’m excavating something for myself. It’s something that I haven’t seen excavated anywhere else in fiction. I’m on my own mission and that’s interesting enough to keep me at my desk.

Speaking of heartbeats, can you speak more about the character Ondie, who is surplus, but without Gwen’s gifts? Some of the scenes with her were the most textured and gripping.

There’s an example of something where even now I’m not sure made me put her in the story. …Ondie threatens the structure of the book. I’ve located so much of our humanity is things like Gwen’s golden arm that make us different from machines. There’s something about it that’s inexplicable that’s beyond algorithms. You can get them to design a golden arm, but there’s something in us that’s divine that’s exemplified by Gwen’s arm. But then there’s Ondie and she doesn’t have a divine spark. She’s not so special. So just as you’re making an argument for humanity being special here’s someone who’s spectacularly unspecial.

She has a decision to make and you can say she was influenced by—well, I don’t want to go give it away—but finally she chooses to be free. That’s a difficult argument to make in a book that there’s free choice and her humanity lies in that freedom. It would have been difficult to build a narrative on that. An arm is easier to build a narrative on.

Ondie does bring a sense of danger because she is unpredictable. It brought a kind of life to the book, the part of me that said just leave it. You could sort of see a rational argument for cutting her out to focus the book but when you see the finished product it would have been the wrong decision. …I have to live with that discomfort.

For those of us who don’t feel like we have a golden arm or special gift, Ondie feels like a different sort of humanity we can relate to.

Yeah, actually I think it’s really important in terms of just life. But the argument we all have golden arms in order to feel like we matter, is different than the argument of what’s so special about humanity compared to AI. As a mother and a teacher and a human being I don’t ask that everyone is a genius, what kind of world would that be? I don’t see the world that way.

I am also aware that at the moment with AI on the horizon, questions about why we should be the center of the universe have become very real. We can’t hold a candle to some of the things technology can do now. What’s so special about us? Why should we not cede the stage to our own technology? Why shouldn’t we be technology enhanced? What are we trying to protect? What is the thing we’re trying to protect? I’m arguing that there’s this thing called humanity, whatever is.

That’s why the book is so hopeful.

The book is not only about technology, this is the book in which democracy itself is really kind of eclipsed. Any number of any other issues—it’s not only a nightmare, there’s a way in which, even as I’m having a nightmare, that I can’t help but have some hope. Partly that’s just temperament, I am that person. I get it. The world is a mess, but I think in part because my parents are immigrants and I spend a lot of time in other parts of the world, America is a mess, but I’m also aware of the fact that life here is a gift that people in other parts of the world don’t have. We’re so lucky.

One of my Lyft drivers was from Eritrea. He was talking about why people come here. His sister has been studying in Wuhan, she just got back to Africa in the nick of time. There’s no internet. She’s on the brink of getting her PhD and now she’s back in a town with no internet. He basically said there’s no possibility there for anyone. You can survive but you can’t do anything except survive. All the possibilities that we know are closed off.

I’m aware that everything is the matter here but it’s actually still a great country. I have hope placed in the young. A lot of these kids are very on the ball. They are far better educated than I was at their age, they are far more politically aware. Don’t worry—they get it. There’s a part of me that’s genuinely pretty hopeful.

Is there anything you wished people asked you more about The Resisters?

This book is a natural evolution from my nonfiction, my thoughts on culture and differences in self. I wish that when people think about immigrant fiction, or what immigrants are bringing to the culture, I wish they would look at this book as one of the many ways in which cultural difference can produce new things. I wish we would broaden our ideas about immigrant fiction to include things that are not just about the political immigrant experience but a new kind of contribution, a thing that opens new doors. I hope that people will look at it not just as this is new and cool, but that an immigrant, a daughter of immigrants, drawing on her immigrant past to open this door.

Gish Jen has published short work in the New Yorker, the Atlantic Monthly, and dozens of other periodicals, anthologies and textbooks. Her work has appeared in The Best American Short Stories four times, including The Best American Short Stories of the Century, edited by John Updike. Nominated for a National Book Critics’ Circle Award, her work was featured in a PBS American Masters’ special on the American novel and is widely taught.

Jen is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She has been awarded a Lannan Literary Award for Fiction, a Guggenheim fellowship, a Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study fellowship, and a Mildred and Harold Strauss Living; she has also delivered the William E. Massey, Sr. Lectures in the History of American Civilization at Harvard University. The Resisters is her eighth book.