Pamela Erens is a graduate of Philips Exeter Academy and Yale University and the recipient of a 2014 fellowship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. Reader’s Digest called her One of 23 Contemporary Writers You Should Have Read by Now. Her short fiction, reviews, and essays have appeared in many publications, including the Boston Review, the New England Review, and Tin House. A former editor at Glamour magazine, her sharp, tender, evocative prose has earned her comparisons to such literary luminaries as Vladimir Nabakov, Edith Wharton, James Salter, Knut Hamsun, and Samuel Beckett.

Pamela Erens is a graduate of Philips Exeter Academy and Yale University and the recipient of a 2014 fellowship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. Reader’s Digest called her One of 23 Contemporary Writers You Should Have Read by Now. Her short fiction, reviews, and essays have appeared in many publications, including the Boston Review, the New England Review, and Tin House. A former editor at Glamour magazine, her sharp, tender, evocative prose has earned her comparisons to such literary luminaries as Vladimir Nabakov, Edith Wharton, James Salter, Knut Hamsun, and Samuel Beckett.

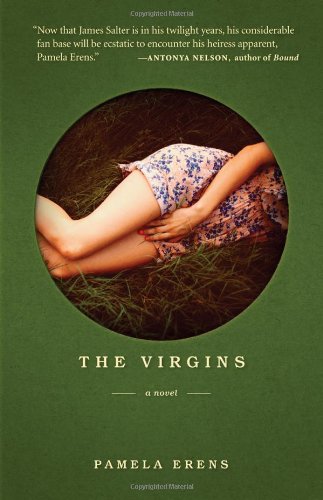

Erens’ debut novel, The Understory was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and the William Saroyan International Prize for Writing while her second novel, The Virgins, was a New York Times Book Review and Chicago Tribune Editors’ Choice. The Virgins was also named a Best Book of 2013 by The New Yorker, The New Republic, Library Journal and Salon in addition to being a finalist for the John Gardner Book Award. The Guardian observed that “The Virgins reminds us that youth is filled with petty cruelties, ferocious yet fleeting desire, sexual competitiveness, but it is also a time of overwhelming loneliness. It is hard not to feel a keen ache of recognition when [the narrator], watching yet another embracing couple, ponders the infinite number of ways there are ‘to be left out, to be abandoned’” while John Irving wrote in The New York Times, that The Virgins “is both skillfully crafted and dangerous” as well as “flawlessly executed and irrefutably true.”

Set in 1979 at an elite East Coast boarding school, The Virgins is narrated by WASP Bruce Bennett-Jones, who is transfixed by the relationship between his classmates, Jewish Aviva Rossner and Korean American Seung Jung, a notorious couple at Auburn Academy. All are looking for liberation from unhappy childhoods, but their lives at school are as complicated as at they are at home.

Pamela Erens talked to Dead Darlings about the creative process, the tensions between adults and children, the conflict between outward appearances and inner realities, human desire, and the importance of editing and influence in writing.

Your book naturally raises comparisons to A Separate Peace and some of John Irving’s work (both influenced by the authors’ time at Exeter, as is yours) as well as to other books like Prep, set at Groton. When writing this book, did you read or reread any of those books and if so, how did the history of prep school novels influence you in terms of your writing and plot choices?

The only boarding school novel I reread while writing The Virgins was A Separate Peace. I can’t even remember what my aim was in doing so—just to remember what John Knowles was up to, I guess. It’s a wonderful novel, so assured and moving. I wasn’t really conscious of trying to join or respond to some lineage of boarding school books. I wasn’t even aware that there were so many such books until The Virgins came out and people started naming them. I foolishly thought that my subject matter was pretty unusual.

The book notes that, “Auburn was freer than any place we’d ever been. There were no parents here and little supervision.” The adults and children seem to be at cross-purposes in this novel. At best, they can be somewhat distant from one another; at worst, they are neglectful or even abusive. How did that idea of tension between adults and children or teenagers help you to create tension in the novel?

The book notes that, “Auburn was freer than any place we’d ever been. There were no parents here and little supervision.” The adults and children seem to be at cross-purposes in this novel. At best, they can be somewhat distant from one another; at worst, they are neglectful or even abusive. How did that idea of tension between adults and children or teenagers help you to create tension in the novel?

The tension comes organically from the situation, I think. I do see teenagers and adults as inhabiting almost non-intersecting realities. The problem is a fundamental, metaphysical one: We can’t see inside other people’s heads. We can’t feel their feelings. This is universally true, but it becomes uniquely problematic when you’re dealing with adolescents. If you are the parent of a small child, you may not always know precisely what her experience is at all times, but you can have a pretty good idea, and it’s a reasonably straightforward task to keep her safe and healthy. And if you are an adult with another adult, you’re not wholly responsible for that person’s well-being. But if you are an adult responsible for an adolescent—as a parent or someone in loco parentis at a boarding school—you have an almost impossible dilemma. The adolescent is old enough to put her ideas and feelings into action in the world, outside of your sight and hearing and control. She’s old enough and complicated enough to hide her thoughts from you, and probably will. You’re trying to mold and shape her in whatever you think is a good and healthy fashion, and you’re only seeing six percent of what’s going on with her.

Long answer. But I have strong opinions about this. Many people have responded to The Virgins with expressions of outrage over how terrible the parents and teachers are. I think some of the adult characters are more sympathetic than others, but no adult can easily control what happens to a teenager, not in an open culture like ours. The best one can do is provide a safe and stable environment and be a really good listener. To the argument that the school in The Virgins is lax in allowing all that sex and drugging to go on, well, I’ll just ask how frequently adults, no matter how stringent their rules, manage to prevent some percentage of a large group of adolescents from finding ways to have sex and partake of illegal substances.

There is a theme of intoxication in the novel, both for coping and for socializing, for example Bruce’s mother, Seung’s idea of the inside versus the outside, the way Seung thinks he can touch reality through drugs. This theme seems to imply that this world of apparent privilege requires a variety of escape routes. Why?

I don’t think that the economically privileged characters in The Virgins require a variety of escape routes because they’re privileged. I think they require escape routes because human beings require escape. Escape from certain desires or from boredom or disappointment or fear. Again, how many people do you know who rely on drink or comfort foods, or lose themselves in video games or compulsive exercise or ill-advised sex or workaholism? I think psychic balance is fleeting for most people.

At different points, when Aviva or Seung get high, they feel a separation between what is inside and what is outside of them. These kids seem to fear themselves, their own thoughts, their own desires. Aviva says that “to be utterly inside them [thoughts] means dissolution” and the joy she can get from eating something delicious also terrifies her. Why do you think that Aviva and Seung are so afraid?

Because adolescence is really scary! It was for me, and I see my own kids coping with various things, and every time I talk to friends about their teens I think: Yeah, yeah, this is such a tough age. And I’m only hearing about the stuff my friends know about! It goes back to some of the things I said about the non-intersecting worlds of teenagers and adults. Small children have terrifying thoughts and feelings, but they at least have Mom and Dad to keep them feeling minimally safe and okay. Becoming an adolescent is about realizing that—oh, shit!—Mom and Dad aren’t magic after all. They actually can’t keep you safe. Bad things can happen—and not just car accidents or diseases, but bad things from within. Powerful desires you can’t control. Self-destructive inclinations. Heartbreak.

Would anyone really want to argue that desire is not scary? Why are people constantly following diets to deprive themselves of the food they love to eat, or struggling to keep themselves from falling in love with people they know are bad for them, or failing to stay within their budgets? Human life is one long battle with desire. And, again, adolescence is where it starts being one’s own battle, rather than one that Mom and Dad manage for you.

Bruce admits, “I’m inventing Seung, too, of course. It’s the least I can do for him.” Why?

Bruce is narrating the novel from many years later, having carried feelings of guilt all this time. He believes he’s done something terrible that he can’t undo. It seems to me that one of the few things one can do in such cases is try to see clearly and fully who one’s victim was, to return his humanity to him. Bruce doesn’t know exactly what was going on for Seung at the time he’s speaking of. He doesn’t know what led to Seung’s actions and Seung’s fate. So, drawing upon clues and hints, he tells himself a story about Seung that seems to fit the facts. As an adolescent, Bruce acted blindly and selfishly. Now he thinks perhaps he can bring some measure of right to his wrong by attempting to see the story without himself at the center of it.

But of course there’s great ambiguity here. Since there are so few facts for Bruce to go on, he is—as he says—doing a lot of inventing. He’s relying, perhaps arrogantly, on the power of his intuition and imagination. Who is he to decide what the truth really was? Later in the book, Bruce says that telling someone else’s story is in some ways “an expression of sadism.” He means that a storyteller puts words in other people’s mouths, makes them act this way or that. And is Bruce truly telling this story “for” Seung? Isn’t he doing it more for himself—to lighten the burden he feels?

These, anyhow, are the contradictions that I hope are packed up in those two lines.

Bruce’s father is a judge, referred to as the Judge. Do you see Bruce as a judge too?

That’s an interesting question. Maybe. Above all Bruce is trying to render judgment on himself. But perhaps he is also trying to decide on the degree of Aviva’s complicity, Seung’s complicity, even the school’s complicity, in what happens. Maybe just as all storytellers are sadists, they’re also judges.

Which development in the writing of the book, in terms of plot or character, surprised you the most as you were working?

I don’t remember huge surprises about plot or character. However, there’s a certain amnesia that sets in after a book is finished—probably as with childbirth. Anyway, can I alter this question somewhat? Can I ask myself which public reaction to an element of the novel has surprised me most? I have been surprised at how much readers despise the character of Bruce. I think he’s quite human. I want to remind readers that every bad thing they know about him comes from him. He’s the one telling us about himself. He’s fessing up to certain ugly thoughts and desires that plenty of people have but don’t fully admit to themselves or at least don’t reveal. Also, if you get to the end of the novel and think about what Bruce has actually done, as opposed to what he’s merely thought about or imagined or almost done, what can you chalk up to his account? I’m not saying there’s nothing, but where does it fall on the spectrum of badness? Also: Has Bruce even done as much as he thinks he has?

Did you always have a clear idea of the ending, or did the end come to you in the process of writing?

I did always know the ending. I knew what would happen, if not exactly how. With all three of my novels—the published two and the one I’m working on now—I’ve known where things would end up before I started. There is always a lot that changes, but the endings never seem to change. Knowing the end helps me enormously. The process of writing a novel can be overwhelming, so if I can see my ending like a lighthouse beam in the distance, I at least know how to narrow down my choices. I need to get from A to B: what is and is not going to be in line with that destination?

The Virgins is your second novel. What was different about the experience? What did your first book, The Understory, prepare you for in terms of writing a second novel? What didn’t it prepare you for?

In many ways writing The Virgins was easier than writing The Understory. After the latter was accepted for publication, I completely overhauled it, start to finish. My editor wanted some changes, and once I started to make them, I felt the whole thing needed to be taken apart and re-conceived. It was a long and sometimes uncertain process. The Virgins proceeded more straightforwardly. I had confidence that I could do this thing called completing a novel, because I had done it once before. However, the novel was originally longer by a third; it had a second part that took place 25 years later. My agent—she was my prospective agent at that point—thought it didn’t work, and we dropped it.

By the way, the writing of that last third of the book had taken twice as long (two-and-a-half years) as the writing of the first two-thirds. In retrospect I think it took longer because I wasn’t sure of my idea. I didn’t have a strong focus to pull everything together. Not that taking more time necessarily means a bad outcome when writing. But in this case, in retrospect, it was the symptom of a problem.

You’d think I’d be in great shape for novel number three. If number two was easier than number one, number three should be easier than number two, right? Wrong. I had a long period of trial and error with this one before I figured out (I think! I hope!) how the story needed to be told and what fell within its purview.

You were an editor at Glamour. What did magazine editing teach you about novel writing?

Glamour taught me to get to the point and to be clear. When I was hired, at age 25, the editors I reported to were very open to me doing some (unpaid, on my own time) writing for the magazine. There were various columns and items you could put yourself forward for. I remember getting back something I’d submitted with the phrase “Throat clearing!” scrawled next to the first paragraph by the editor-in-chief. She was totally right. None of my college professors had broken me of my default let’s-back-into-the subject approach. They tended to be focused on other things in my writing than clarity and concision. Unfortunately.

Of course any kind of editing work gives you practice in spotting slackness and imprecision. But the writing I did for Glamour taught me more than the editing, which was 95 percent of my job. It’s always easier to see infelicities in other people’s writing than in your own.

Which books or authors did you read as a kid that made you want to be a writer?

I loved the Oz books as a kid and remember being in my school library in first grade and deciding that I too wanted to write a series of books. But I was a very serious little kid and I determined that I was only going to write books for grownups (even though I didn’t yet read books for grownups), not children. Johnny Tremain, which I read in fifth grade, was tremendously exciting to me—this idea that you could drop a fictional character into real history. I imitated it with a long narrative about a slave girl who escapes to the North before the Civil War. It got published because my mom sent it around and a small press took it. A little later, I got kind of lost, writing-wise. Maybe I was distracted by becoming a teenager, but I would start things and I couldn’t finish them anymore. Then, at 15, I read The World According to Garp and it was like being shot out of a cannon. I couldn’t believe a novel could sound like that, behave like that—could be so irreverent and energetic and up-to-the-moment. I started writing again, very imitatively. Then, at 17, came Proust. Another “wow, novels can be like that?” experience. Now I loved the slow, speculating, analytical narrator. I loved the intellectualism. Probably Proust had a very bad effect on my own writing efforts, as did, later, George Eliot and Edith Wharton and Henry James. I’m not magisterial. I wanted to be, for a long time, but, um, no.

Who are your biggest influences now?

I’m influenced by just about every single book I read. Everything gives me one idea or another about what I’m working on—what elements I might try to copy. So I’ll just talk about what I’m reading right now. I’m in the middle of the second volume of Karl Ove Knuasgaard’s My Struggle. Incredibly stimulating. I love it. I was at the Brooklyn Book Festival a few weeks ago and there was a panel on contemporary writers who are intentionally blurring the distinction between fiction and autobiography, who are very interested in unpacking the moment-to-moment experiences of one mind. Like Proust, but less clearly fictionalized. Besides, Knausgaard, there’s Ben Lerner, Teju Cole, and Sheila Heti. I’m fascinated by these writers. Sometimes I love what they do and sometimes they aggravate me. Mostly I’m into it. I don’t think I’d ever try to write like them, but anything that fascinates one can’t help but influence one somehow.

I’m also reading and rereading Virginia Woolf, primarily Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse, for the novel I’m working on now.

If you want to learn more about Pamela Erens, check out her website.

1 comment