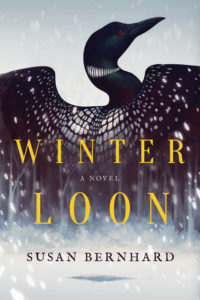

We at Dead Darlings are delighted to introduce you to one of our very own, Novel Incubator alum Susan Bernhard, and her spectacular debut Winter Loon (Little A, 2018). This novel is just out and it is breathtaking. Already it is being called a raw, beauty of a page turner that is completely spellbinding and I couldn’t agree more. The novel will break your heart as much as it will fill it and once you start reading, you won’t want to stop.

We at Dead Darlings are delighted to introduce you to one of our very own, Novel Incubator alum Susan Bernhard, and her spectacular debut Winter Loon (Little A, 2018). This novel is just out and it is breathtaking. Already it is being called a raw, beauty of a page turner that is completely spellbinding and I couldn’t agree more. The novel will break your heart as much as it will fill it and once you start reading, you won’t want to stop.

The coming-of-age-story follows Wes Ballot, a fifteen-year-old who watches his mother let go of an ice ledge and drown in a nearly frozen Minnesota lake. This crippling loss is made worse by Wes’ father who abandons him afterwards, leaving Wes with his cold-hearted grandparents. Cocooned in his mother’s childhood bedroom, Wes tries to piece together the kind of past that would make his mother want to let go and finds himself flailing until a local girl captures his heart. Her love gives him the strength to launch a desperate search for his father; a search that forces him to choose between his only surviving parent and the girl who’s helped put him back together again.

Read this book. The raw, real emotion will suck you in and you won’t want to put it down. We at Dead Darlings were thrilled when Susan agreed to this interview, so let’s get to the good stuff:

Most of our readers are writers—and we want to know: Susan, are you an outliner or a pantser?

I am the worst kind of pantser. I’ve written myself into the wilderness so many times. It’s incredibly frustrating to be lost in your own work with no clear path to get you to the other side. I swore when I was done writing Winter Loon that I would never work without an outline again. So, when I started a new project, I created this incredible scaffolding using source material and strategically placed plot points. I pasted it to my office wall with oversized neon Post-Its. I was so proud of myself!

Then I sat down to write and the characters stared back at me, blank faced, arms crossed, defiant. I tried coaxing them into this magnificent structure I’d created and they refused. So I tore the whole thing down and started working by the seat of my pants again. Suddenly, the characters came alive for me. So, I’m giving myself latitude at least with the first draft to let go of the reins and let it run for a while. I learned so much in the Novel Incubator about structure, spines and arcs, and revision that I do think I will be in much better shape when I get to the end of my next first draft.

Talent alone did not get this fantastic book published. You fought for it tooth and nail–and the book world is better for it. Can you tell us about the process and maybe offer advice for all our hopeful readers toiling away at their drafts and/or query letters?

I had no illusions about how difficult the publishing process would be, especially once I became part of a community of writers at GrubStreet. It took me five years to write the novel, four of which were spent revising after the first draft. But, still, I was so excited to start the agent search. I sent out ten queries and received multiple requests for the full manuscript. Fast forward months and months later, dozens and dozens of queries, requests, and rejections later, and I still didn’t have an offer. I was resigning myself to the possibility that I would never get an agent or sell my “bleak” book (this is what I heard most often) and I’d get very frustrated when well-meaning people offered platitudes and told me not to give up. For me, that hopefulness was actually oppressive because the truth is, no artist of any measure is guaranteed any kind of commercial success based on wishful thinking. I know writers who’ve written amazing books that don’t see the light of day and others whose work doesn’t achieve anywhere near the level of attention that it deserves.

Sometimes books don’t sell. I’d come to recognize that reality not as failure, but as one possible outcome of the writing process. About a year after I’d first queried Winter Loon, I queried an agent who was known for responding quickly. He asked for the full manuscript the same day and by the end of the week, he offered representation. Less than two months later, I got the offer from my publisher. I’m glad I hung in there and I’m so excited to have the privilege of working with an amazing editor and holding the finished novel in my hands. I’m glad I persisted but I maintain that it still could have gone another way. As writers, we have to love the writing process, create a supportive writing community, and be good citizens of that community because the marketplace is not always a welcoming place. Control what you can. Be kind.

You tackle a lot of difficult issues in Winter Loon. On one hand, I kind of loved Loma, the way you described the town itself, its people and the seasons. But then there’s this underlying bigotry, issues of domestic abuse, and the divide between the haves and the have-nots. Did you work from what you knew or from research?

The best of Loma—the sights and scents, the gentleness and humor—is an homage to the small towns and the people I knew growing up in Montana. The bigotry on display in Winter Loon was evident in those small towns but also in every city where I’ve lived, from San Francisco to Indianapolis to Birmingham, Alabama and right to Boston. So many of the issues the characters in Winter Loon are forced to deal with are all tangled up in each other.

Once I started writing the characters, putting them in difficult situations, I also had to imagine what led them to those brinks in the first place, what factors played defining roles in their decision-making. I interrogated each character’s background, learned about inherited trauma, and delved a little bit into the roots of domestic violence, to try to understand my characters, especially the women from Valerie, Wes’ mother and Ruby, his grandmother; to Jolene and her mother Trudy; even to Aveline and Annaclaire. Where are prejudices born? What is a victim? How do we break the cycle of pain? That’s what I was interested in. There was an article in the New York Times recently about children born into homelessness and how the cycle that got them there repeats and repeats. Persistent poverty, systemic racism, poor education, domestic violence, lousy nutrition—it all takes a toll. Wounded people live and work among us no matter where or how we live and those wounds can lead to reckless acts, small and large.

Speaking of love/hate. I can’t imagine that developing someone as hateful as Gip was easy. Can you tell us how you did it? What was the biggest challenge?

One of the hardest things about creating a fictional villain is giving him a dose of humanity. That was difficult with Gip, Wes’ grandfather, given his transgressions. Wes doesn’t know his grandfather well because Gip hides behind a mask of bitterness. So we as readers don’t know what makes him that kind of person who is so deeply aggrieved and, ultimately, so dangerous. I did try to give him moments—though they’re admittedly brief—where you might feel a bit of sorrow for him. He’s a hurtful, harmful man but, however twisted and sick he might be, I believe he mourned Valerie’s death deeply.

Ruby, Wes’ grandmother, was one of my favorite characters. She appeared heartless, but I thought that was a veneer she fought hard to maintain. Under it all she was soft for her daughter and Wes, and I was certain she’d break down and let us see that during the scene in which she asked Wes if he’d ever noticed the scar across Gip’s belly. I waited for her to cry and hug her grandson. But she didn’t. I imagine writing her character, and that scene, was one of the toughest challenges in this novel. Can you tell us how you came to understand Ruby? And what you were thinking as you wrote that epic scene?

Of all the characters in Winter Loon, I think I grew to love Ruby the most. I’ve never known anyone like her; she was an invention and a surprise to me. I so wish I could have given her more peace. But she’d been hurt too much, too deeply. Love for her, intimacy, was a frightening thing, something she had to guard against. When I was little, I used to climb into my mother’s lap with a blanket and lay my head against her ample breasts. I’m a grown woman but I still close my eyes to summon the warmth and safety of that spot.

Ruby never had that kind of safety, not in her whole life. I tried to give her a sense of it in the moments she describes to Wes, dancing with her friend Maureen. But even that was fleeting. She told Wes she came from “the hard part.” I believed that about her, that this woman had long moved past the expression of love. What I tried to do though was imagine her innermost thoughts—the things she longed to say or do that were so far out of her reach. She didn’t know how to be a wife or mother, let alone a grandmother or friend. What courage she had to muster to go on with each day—to go to work, to buy groceries, to make a lousy meal! And she knew very well her burdens and flaws. I imagined her getting dressed in them every day, tugging them on with her pants, pulling them over her head like a hairshirt. But her final gesture to Wes was an act of deep love and unburdening.

The book ended with Wes as happy as we’d ever seen him. Then came the epilogue, which I thought was perfect, because it revealed that happiness wouldn’t actually come so easily for him. Authors often struggle with prologues or epilogues – to use or not to use? Can you tell us why you decided to add the epilogue? And any secrets on using one so well?

Winter Loon covers a lot of bleak themes. Like I said earlier, more than one agent rejected the novel because they said it was too dark. When I finally sold the book, I had a conversation with my editor at Little A, Hafizah Geter, about that. She said, “People lead shitty lives. Put on your pants and read the book.” A reviewer on Goodreads echoed that, saying, “In the age of noisy adventure novels and sweeping political metaphors, Bernhard reminds us that sometimes people’s lives are just quietly shitty, with no conspiracy or reason, without any real institution that can be boycotted or revolution that can be founded.” In writing the epilogue, I wanted to give a sense that we push on despite hardship, pain, and loss. There is plenty of suffering in the world but there’s plenty of simple joy, too. Most importantly, Wes needed a reason to be telling this story at all, he needed maturity and the vantage point of time to make sense of this devastating year. And don’t we all have to work for our happiness? Isn’t that what makes our lives fulfilling in the end, that labor of love?

Our readers LOVE this one. What was the biggest editorial change you made while editing Winter Loon?

It was kind of a rookie mistake on my part to put twists in the narrative and call it plot. In the Novel Incubator, I scraped through the whole manuscript and stripped out everything that I called a “turns out” plot point. Turns out, this person is dead! Turns out, that person lied! Once I removed those spikes, the story unfolded a bit more fluidly. I got excellent advice from literary agent Gail Hochmann at the Muse and the Marketplace Conference. She reminded me that time heals wounds. Initially, I’d given my characters too much time to get over Valerie’s death. So the most impactful change I made was condensing the timeline from about ten years down to one, which raised the stakes and put more pressure on Wes, Ruby, and Gip to come to terms with the past.

Finally, let’s get personal. You work in a bookstore and read more books than anyone I know! What are you reading now? What upcoming debuts do you recommend?

Right now, I’m reading two books: an advanced copy of Women Talking, the newest novel by Miriam Toews and James Charlesworth’s debut, The Patricide of George Benjamin Hill. These two books couldn’t be more different from each other but I’m loving them both. Miriam Toews is an incredibly beautiful writer all the way down to the sentence level and Women Talking is phenomenal and important. I think it’s going to garner serious attention in 2019. Patricide is rapid-fire and dense and muscular. I love the way Charlesworth packs his sentences and his characters have this grand, epic, fated quality. In memoir this year, I was devastated by Therese Mailhot’s Heart Berries and in sci-fi I was entranced by The Book of M by Peng Shepherd. I’m also really looking forward to Whitney Scharer’s debut The Age of Light, Katrin Schumann’s debut The Forgotten Hours, The Stationary Shop by Marjan Kamali, and The Chef’s Secret by Crystal King. Oh and there’s this other one, A Bend In The Stars by Rachel Barenbaum. My TBR pile is ridiculous.

About Susan Bernhard: Susan Bernhard is a Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowship recipient and a graduate of the GrubStreet Novel Incubator program. She was born and raised in the Bitterroot Valley of western Montana, is a graduate of the University of Maryland, and lives with her husband and two children near Boston. Winter Loon is her first novel.

2 comments