Photo credit: Cameron Dryden

A “verse novel”, or “novel in verse”, is a novel-length narrative told via poetry. It also happens to be one of literature’s fastest-growing categories, extremely popular with young readers. The Song of Us is Kate Fussner’s debut novel in verse, a Middle Grade love story between two seventh-grade girls, mirroring the Greek romantic tragedy of Orpheus and Eurydice. The protagonists must learn to love themselves and one another, and to fight for one another. The novel’s first-person language is fresh; the lovers’ despair, heart-rending; and its visual poetry, captivating.

I spoke with Kate, a former Grubstreet student and former English teacher to Boston Public Schools middle and high school students, to learn more about the medium and how she stumbled into it.

Cam: Where’d you get the idea for this approach?

Kate: My students loved verse novels. They seemed less intimidated by the novels’ size and flew through them. I had been working on a prose novel for a couple of years and my mentor encouraged me to take a break and try something else. And I had this idea: an Orpheus and Eurydice retelling in middle school, and it had to be in verse.

Why you think verse novels have been so popular with your students?

Many students are drawn to stories, but technology has made it far easier to access content in small bites. Technology has changed our relationship to the length of what we expect. It’s changed how consume stories, like I might want to binge a whole TV show this weekend. A student would tell me, I’m gonna watch this whole thing. They want to consume fast. Novels in verse are approachable, although they require complex thinking on the reader’s part.

Why did you decide to write this particular book?

I love teaching middle school. There’s something so incredible, imaginative, wild, and weird about 7th grade. Some students are starting to think about going to parties, vaping, and sneaking out of the house. Others in the same class are wearing Disney backpacks, still very much connected to that younger childhood space. I find it beautiful and fascinating to have the imagination of childhood and the uncertainty of adolescence settling in at the same time. And now so many more stories are being told outside of the white, heterosexual, cisgender, Christian-American, middle class family perspective. I was really moved by what I was seeing in children’s literature and wanted to be a part of it.

I noticed that we have two mutual friends who’ve taught in the Boston Public Schools: Neema Avashia and Dr. Kandice Sumner. What have they meant to your writing journey?

Neema’s one of my closest friends. Very early on in my teaching at McCormick Middle School, I connected with her because she was the teacher to go to if you were having trouble figuring out what you were doing. Neema published Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place, last year. I’m very grateful for how she’s been a mentor to me. Kandice and I met working at Fenway High School. She was one of my first and fiercest friends there and has remained so. We both were working on writing projects, so we FaceTime’d on our computers for accountability. She really helped me stay grounded during the pandemic.

What’s some of the best advice you received on writing your novel in verse?

In my MFA program at Leslie University, Jason Reynolds told me every poem needed to have its own punch, a strong entry and strong exit, and that it needed to be able to stand by itself as a poem as well as inform the larger story. And so that felt like every task was figuring how do I get into this poem, how do I get out of it, and how do I make sure it can stand on its own.

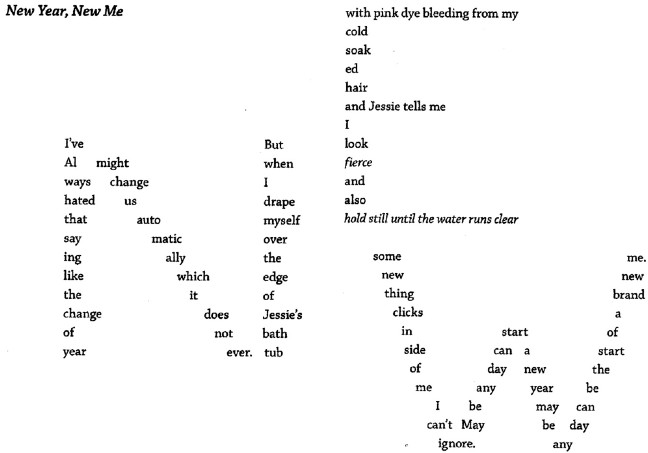

I can’t right now imagine trying to write a novel in poetry. With your publisher’s permission, I included the following sample of the visual poetry from your book:

I’m so impressed! How much poetry have you written?

The last time I wrote poetry was in high school! I consider myself an accidental poet. I never studied it in college but I always loved playing with words. When I realized that writing a novel in verse was like 350 pages of playing with language, the idea became so much more exciting and satisfying. It became like a puzzle. And I just didn’t want to stop working on it. I’m writing two other novels in verse because I’m so excited by the form.

What advice would you offer novelists?

There’s something about this story that seemed so outside of my wheelhouse that it seemed silly to even try because I’d never written a novel in verse. I’d never written for a middle grade audience. I thoroughly felt I had no idea what I was doing. Because I gave myself permission to do it anyway, I got so much more out of it, almost because the thought was so absurd. It can’t possibly work. I think I found my way through it because I let myself try anyway. I want to encourage other writers to try out that idea that seems too far-fetched to work, and to see what happens when we take ourselves a little less seriously for the sake of playing with new ideas.

With all the book bans, do you worry about how The Song of Us will be received?

Have you read my book? (both laugh) Yeah, it’s unfortunate, but it’s the reality of publishing a queer kid lit book right now.

But of course, we can’t worry too much about such things. We can only write the stories we’ve been given.

The fact of the matter is, we end up with book bans because books are powerful. Books are important. I have to trust my book will find its way to kids who need it. At times, it’s both demoralizing and fueling. It says books are important, stories do matter. Don’t let what others think get to you when you sit down and write.

Kate Fussner believes in the joy of reading, and in communicating that joy to young students and their teachers after teaching middle and high school English in the Boston Public Schools for 10 years. The Song of Us is her debut middle grade novel. Kate received the W.K. Rose Fellowship from Vassar College in 2022 and her writing has appeared in the Boston Globe, WBUR’s Cognoscenti, and elsewhere. Find out more at www.katefussner.com or on Twitter (@katefussner), Facebook, or Instagram (@kafussner).

1 comment