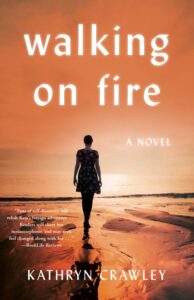

In her debut novel, “Walking on Fire,” author Kathryn Crawley tapped into her early career in speech pathology when she worked at a center in Thessaloniki for Greek children with cerebral palsy from 1974 to 1976.

In her debut novel, “Walking on Fire,” author Kathryn Crawley tapped into her early career in speech pathology when she worked at a center in Thessaloniki for Greek children with cerebral palsy from 1974 to 1976.

The novel features Kate, from Texas, who ventures to Thessaloniki, Greece, in 1974 amid the aftermath of a seven-year dictatorship and rising anti-American sentiment. As she immerses herself in the city, teaching disabled children and falling in love with Thanasis, a Communist, Kate’s loyalty and beliefs are challenged.

Kathryn explained how she used her own exposure to a “cauldron of anti-Americanism bubbling all around” to imagine the exciting plot and anchor her historical fiction.

You have several things in common with your protagonist, Kate. Why did you decide to write this time period of your life as a novel?

When we sold my parents’ house in Texas, I found a box of letters in my mother’s closet, and she had saved every letter I’d ever written. All of my letters from Greece were there. And so when I retired, my writing practice was to sit in my room and sort of dangle my fingers over the box of letters, pull one out, and write for 30 to 45 minutes about that letter. I had planned to write a memoir. But in my writing practice, writing in the third person helped, so I decided to turn it into a novel.

I really enjoyed the way that you demonstrate various aspects of Greek culture. How did you decide to add in details that the reader might not be familiar with? And what things were important for you to include?

I wanted to try to convey things that I love and that were important to me. The food, getting to see tzatziki on the table, retsina being poured, the golden fried calamari. These things help transport me back. I love the culture so much, and so I wanted to share those images.

Also, music was very important because during the dictatorship, everything – even the Beatles – was banned. And so when the dictatorship fell, everything came rushing back in. Music was a really important part of the revolutionary zeal at that time. So listening to albums from that time also helped me when I was writing.

One thing I noticed was that as Kate gets immersed, we also get immersed. One of the ways you do that is by incorporating more and more Greek phrases into her life. We almost learn the meaning of them alongside her. What was your strategy in finding the balance of Greek and English in your novel?

I wanted Greek to be a character of its own. For example, the conversations between Kate and Thanasis, the man she falls in love with, are more intimate because of it. There are things he can only say to her in Greek. But I didn’t want to tire my readers or burden them with too much Greek. I actually started paring down the conversations that were in Greek during editing. So that was difficult to do.

And actually, in the copy-editing process, it was difficult to figure out how to portray the Greek. I was very careful to always indicate the meaning of the Greek words. There were a lot of decisions – like whether to put it in italics or how to treat it in dialogue. I had a very good copy editor to help me make a lot of those decisions and stay consistent.

What do you want today’s readers to understand about this political moment in Greek life? You’re touching on something that happened almost 50 years ago, but reflects some turmoil that still resonates now.

I very much wanted my readers to understand what it’s like to be outside of America and to understand some of the criticisms. In Greece at that time, the Greek people loved America. They loved American music. They loved American films. But because of what happened to them and the CIA-sponsored dictatorship, they did not approve of our government.

In Greece at that time, who your political party was was where you got your identity. And so Kate is friends with a woman who is from the Moscow-leaning Communist Party. In the 1970s, Communism meant something different from what it means today. It’s more of a representative form of government, but it’s still called Euro-Communism. I just hope that today’s readers will still be able to see the importance of a collective society instead of rugged individualism.

Were there any dead darlings in earlier drafts of your manuscript that you had to choose to let go of?

Yes, when I submitted to She Writes Press, my manuscript was 120,000 words, and I very much wanted to be a part of She Writes because of their distribution. So I had to cut 20,000 words, and I had to cut the part where Kate was working with a group of laryngectomized Greek men in the university hospital there. It didn’t move this particular plotline forward. Instead, she is working with kids. Kate has an innocence about her as well, so having her work with children is can act as a mirror.