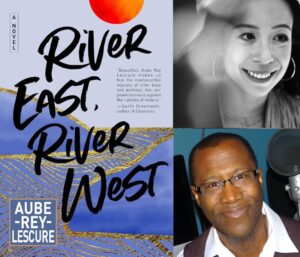

Shanghai, 2007: Fourteen-year-old Alva was born and raised in China by her American expat mother. Her hopes of moving to America are dashed when her mother becomes engaged to Lu Fang, their Chinese landlord, whose own dreams were curtailed by the country’s harsh political reforms. In a stunning reversal of the east-to-west immigrant narrative and set against China’s political history and economic rise, River East River West, Aube Rey Lescure’s debut novel, is a profoundly moving exploration of race and class, cultural identity and belonging, and the siren song of the American Dream.

Shanghai, 2007: Fourteen-year-old Alva was born and raised in China by her American expat mother. Her hopes of moving to America are dashed when her mother becomes engaged to Lu Fang, their Chinese landlord, whose own dreams were curtailed by the country’s harsh political reforms. In a stunning reversal of the east-to-west immigrant narrative and set against China’s political history and economic rise, River East River West, Aube Rey Lescure’s debut novel, is a profoundly moving exploration of race and class, cultural identity and belonging, and the siren song of the American Dream.

You workshopped your novel first in our Novel Incubator class. Now, you’re first to publish! How did you advance your manuscript after class ended?

It was right at the beginning of the pandemic, so my manuscript became a lifeline to get through each day. After querying agents with 140,000 words, I got the message it was way too long. That became a huge kick in the pants to streamline. I cut 30,000 words before querying again. I also took a lecture course at The Shipman Agency with Garth Greenwell, whose book, Cleanness, I greatly admire. He teaches about writing sex, which interested me because of the opportunity to refine key scenes in my book. After the lecture, he offered a six-week writing workshop that I applied for and was accepted.

You’re a human bridge of sorts between cultures. How many languages do you speak?

Four. My native languages are French and Mandarin Chinese, as my parents are from France and China. English is my third language and I write in English because it’s now my dominant tongue. I learned it when I was 10 or 11 as a Chinese schoolchild. I also speak Spanish, which I learned in college.

In your novel you say, “They were finally on summer vacation. The Chinese character for vacation was 假, also the character for “fake,” and if Lu Fang were awake she would’ve asked him if he thought that was on purpose.” How are Chinese characters created?

Many are pictograms with either a left- and right-hand side, or a top and bottom component. In the above example, the left side is the radical for “person” and the right is commonly recognizable to help you guess the character’s sound. Chinese is very hard to learn, but there’s a lot of poetry and a methodology to Chinese character composition. The reader doesn’t need to know the language but can see how these characters are layered, telling a visual story.

About Alva you write, “In the cyberworld they were both glorious rebels, final bosses. And in the real world she, like him, needed a place to spend the night for cheap.” Are there similarities between Alva’s story and your own?

River East River West is most autobiographical in its details of place and social observations. This is a social novel and a kind of place portraiture. On the other hand, my narrative mercifully diverges from Alva’s in its family details and major plot points, though I did a lot of risky things as a teenager in Shanghai. At the time, it felt like a society with very little adult supervision. Luckily, the worst that Alva encounters never happened to me, but it did happen to people around me and I heard about horrors occurring in the freewheeling expat world. I wanted to explore those worst-case scenarios and what-ifs through my novel.

“Shanghai was oppressively muggy, the kind of heavy moisture that bred mosquitoes and slick con men.” That’s such a wonderful description, bringing the reader into the grittiness of the metropolis. When did you live in Shanghai?

From the ages of three to five and again from the age of nine or ten to 16. As a southern Chinese city, it does get quite muggy, humid, and hot during the summers. Like many global metropolises, it has this reputation as a city where anything is possible, but also a potentially dangerous place in terms of exploitation and being hustled. The line you quoted is written from Lu Fang’s perspective and shows his wariness of Shanghai from the point of view of a businessman from a relatively medium-sized, northern Chinese city.

What do you hope readers take away from your book?

I hope to help readers understand China better. Although my novel isn’t about policy issues, I hope it provides a certain immersion in the country to help readers see both good and bad from an insider point of view, and to show how the personal and political interact for various characters of different races.

Like Simone de Beauvoir, Henry David Thoreau, and Virginia Woolf, one of your unique traits is how much you walk!

After college, I completed the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage in Spain a few times. I can’t recommend it highly enough. It’s one of those life experiences that recalibrates your relationship to distance, space, time, and what can be achieved in the course of the day. Now, I have this ingrained mindset that no distance is too far to walk. I incorporate walking in my daily life.

I sometimes take days to just walk 30 to 40 miles to cleanse or reset, or show myself this can be done for both the physical and mental challenge. What’s 24 hours in a day? What can you do with it? Prove to yourself you have the power to shape time and distance.

What advice do you have for new writers?

Don’t rush. At a certain stage in my novel writing and revision, I was so desperate for a sign of approval from the publishing world that I rushed my first round of querying and sent agents a gargantuan manuscript that was quite sloppy. Ultimately, nobody’s here to waste their time holding your hand as you edit a manuscript that’s far from ready.

The other advice I would give writers is find a substantive workshop like Grubstreet’s Novel Incubator. Very few programs have ten classmates read your entire novel manuscript twice! That also means you must read 20 books during the academic year, if you count each book’s revision, but it’s well worth it. Do you agree?

Absolutely! For those of us who take novel writing seriously, it’s life changing, right? The Novel Incubator helped you secure your career as a working writer, so I couldn’t agree more.

Aube Rey Lescure is a French-Chinese-American writer who grew up between Shanghai, northern China, and the south of France. After receiving her B.A. from Yale University, she worked in foreign policy and has co-authored and translated two books on Chinese politics and economics. She was the 2019 Ivan Gold Fellow at the Writers’ Room of Boston, a Pauline Scheer Fellow at Grubstreet, a finalist for the 2018 Boston Public Library Writer-in-Residence program, and an artist-in-residence at the Studios of Key West and Willapa Bay AiR. Her fiction and creative nonfiction have appeared in Guernica, Best American Essays, The Florida Review online, WBUR, and more. Find out more at www.aubereylescure.com, on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.