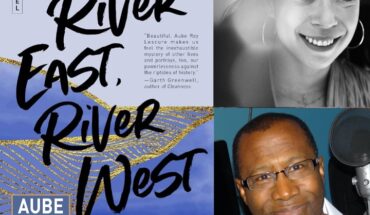

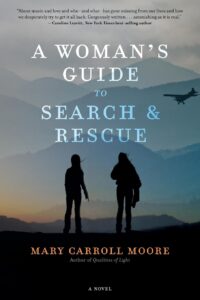

Many of us know her from her newsletter, Your Weekly Writing Exercise, chock-full of craft tips, writing exercises, and inspiration; or have used her book, Your Book Starts Here, to plot our stories. We’ve benefitted from her W-structure workshop and participated in her writing retreats. Mary Carroll Moore became a published fiction author in 2009 with her debut novel, Qualities of Light. Her follow-up to that acclaimed novel, A Woman’s Guide to Search & Rescue is coming out this fall. Kirkus called it “an exciting work of survival fiction with strong female characters.”

Many of us know her from her newsletter, Your Weekly Writing Exercise, chock-full of craft tips, writing exercises, and inspiration; or have used her book, Your Book Starts Here, to plot our stories. We’ve benefitted from her W-structure workshop and participated in her writing retreats. Mary Carroll Moore became a published fiction author in 2009 with her debut novel, Qualities of Light. Her follow-up to that acclaimed novel, A Woman’s Guide to Search & Rescue is coming out this fall. Kirkus called it “an exciting work of survival fiction with strong female characters.”

I was delighted to speak with Mary about her inspirations, the themes in her novel, and her writing style.

Bonnie: You have a dedication to your mother, a WWII pilot, at the beginning of the novel. Do you fly yourself?

Mary: I waited most of my life for my mom to teach me, because she said she would. And she of course was a fifties housewife and had a full-time job and four kids to raise, so there was no way. So, I passed into adulthood really wanting to fly and almost taking lessons a bunch of times. And finally, when this book was coming out I thought, “I’ve got to get to it.” A friend knew of an instructor nearby, at a little airport about 20 minutes away. I went several weeks ago and had my first lesson, which was cool. I really enjoyed it. Wow, it’s so much to learn. I’m kind of boggled by how much my mom knew and how good she was.

Did she ever fly again after she became a housewife?

She worked for Pan Am for a while after the war. She did executive flying for people from their office to their home, things like that. So, she was a commercial pilot for a little bit, and then she got pregnant with my older sister. I guess she decided that it was too risky to fly with the baby, so she decided to stop. And I always thought she probably regretted it, but life just took over.

Flying together was a really funny thing. She would sit next to us and mutter instructions to the pilot as we were flying in these huge jets. She didn’t ever fly a jet, she flew four-engine prop planes, but she would say, “Get those flaps down,” and all these little instructions as we flew. So I grew up with that legacy too, my mom co-piloting from the back of the plane.

You probably thought it was totally normal for one’s mom to know how to pilot a plane.

I didn’t even consider it unusual. I would tell my friends when I was a kid and they were just kind of like, “No, women don’t do that.” I grew up with this idea that women did extraordinary things, which was kind of neat.

That’s great. And it leads into my next question, which is how did your mother’s experience impact you? And impact your writing?

It planted a seed in me that I could pretty much do whatever I could do. You know, I didn’t have the limits of a traditional female role in my life. I was able to do crazy stuff. Like I lived in Europe for a year. I hitchhiked around Europe. And I started a cooking school in California when I was in my twenties and drove across country by myself in a little Volkswagen. You know, all these little things that I did that were kind of outside the box. And I think it was because my mom was so accepting and really encouraging her daughters to be whatever they wanted to. They didn’t have to stay in the traditional roles, even though she herself went back to that role after the war to take care of her kids and be a wife to my father and work and all that stuff. But she was very, very smart. She’s a genius level intellectually, and she just always felt like women could do whatever they wanted to.

So that’s the legacy I brought into the book. I wanted to put three characters in constrained situations where they weren’t believing that, and then slowly, with the help of each other, rescue them from that limitation in themselves so they would come to the place where they decided that they could do whatever they needed to do. And that’s kind of where my mom’s legacy and her teachings to me as a kid came forth in the characters of this book.

Yeah. That really came through. I love the strong women characters.

Thank you. I think that’s one of the most common remarks that reviewers have made, like Kirkus. They constantly are bringing up the strong female characters, which is so gratifying to me because that was one of my main points with the book, is to create characters that had incredible strength and insight. Even if they didn’t recognize it themselves in the beginning, they were able to eventually tap into it.

You include a lot of great details about flying for someone who isn’t a pilot yourself. Did you have to do a lot of research?

Oh God, yeah. I had a team. I was lucky enough to have two pilots in my class when I taught at The Loft in Minnesota. One of them was a flying instructor, and she came to a lot of my classes. She was working on a wonderful novel at the time. And I finally said, “Sylvia, are you willing to answer some questions from me, because I’m a real rookie and I need to know if this works.”

So the first thing I did was say, “If somebody was going to crash-land a plane in a remote gorge and the plane was going to explode and they would walk away alive, what kind of situation would it have to be?” And so she had this cohort of three other instructors, and she took it to them and they worked on it for a month, and they came up with four scenarios that would actually be plausible from a flight instructor’s point of view. And I tested them out and I wrote them into scene, and some of them didn’t work because the scene didn’t work. And then I ran the final one by her and said, “What would you adjust here in the wording or the details to make it real?” And she helped me with that.

And it was such a gift because, honestly, it’s like anything you do in writing where you have to research a topic you don’t know about. People are really willing to help.

You have this quote on your website: “I write about women heroes. Not obvious ones and not immediate ones, but women who are searching for freedom and worth in their lives despite complicated, risky circumstances.” It sounds like your mother was an inspiration for that, but did anything else inspire your wanting to write about women heroes?

Well, this is going to sound a little sentimental, but right now in the world, there’s not a lot of hope. Everybody’s kind of crushed by everything that’s on top of them. And I wanted to kind of give a conclusion to the book, a story that would inspire some hope that people are basically able to rise above circumstances and find freedom if they want to. And so I took three people that were really limited in their own minds by their circumstances, either by enforced situations like illness or betrayal or something. Their past was very strong in all these people, and they carried around that past like a burden. And I wanted to show how part of heroism in women, mostly in my experience, has to do with letting go of some of the past and allowing yourself to actually be a possibility to change and to be something better than you’ve been.

Each of them had to do it in their own way. Kate had to let go of her betrayal by her husband, and also the limits of her illness. And for Molly, it was the fact that she felt unworthy of love. I wanted that to be something she had to face at the end. And with Red, she grew up being an outlier, so Red never got a sense of who she was and what she belonged to. I think all of those traits are kind of heroic, you know, when women can let go of the thing that’s limiting them.

It seems like you were also trying to get across the importance of family relationships, of these two half-sisters finding each other.

Yeah. And your biological family is really important in your life, but your found family can be a source of family as well. Red needed somebody to really accept her so she could belong. In the beginning, she was very much self-focused and needed to save herself without really realizing the cost to other people. And at the end, she was somebody that really wanted to serve others and have a good relationship, one built on trust and love and something she really hadn’t had except with her mom.

I love the story of the rock band. Do you have any experience with that or was that just an idea you came up with?

I do. I’ve never been in a rock band, but I’ve been in a band. I’m a backup singer and a poor guitarist. I’ve been in several singing groups, and I was in a band called Wave for a while, a five-person band for pop rock and folk. We performed a little bit in New England, but not much. But I’ve always loved music and the whole idea of it.

I also love the setting of the Adirondacks, the ruggedness. And the impending snowstorm brought a lot of drama. That’s so pivotal to the story, right? Because she’s stuck there, she’s snowed in. Do you have a connection to that area?

Oh yeah. My grandmother was another outlier. She was my mom’s mom. And she was always very community service oriented. She founded a camp for kids in the Adirondacks when she was in her thirties or forties. She was a counselor at this camp, and the woman was selling it, and she bought it. And she ran this camp for about 30 years. We got sent there as kids starting at age six for two months every summer, until I was 16. It was a really remote, beautiful place. It’s still there. It’s gorgeous.

It was a hiking camp, so it was all about mountain climbing. The scenes that I have in the book where they’re hiking on Giant Mountain and some of the other places are real. They’re actual places. It’s fictionalized. The trails that I created are not exactly what they have there, but they’re similar, so there’s a lot of authenticity about the setting for me.

The character of Molly was in your previous novel. Is this book a sequel?

Yeah. Which is risky to write, but I couldn’t stop. Originally in the early drafts, I changed all the names and created a different location, and I was writing these people, these lives that were creating a good story, but it wasn’t the story I needed to write. So towards the last year of revision, I decided, “Well, what if I went back to the original names of the people that were in the first book?” Molly and Kate and Mel were the three. And Sarah, the cousin, was also in the first book. Red is not. Red is completely new to the story.

So I did, and it felt so much more right to me, more of a … I don’t know. An integral part of the story was what happened to Molly and Zoe five years later or three years later. So I felt very happy about that. It was like coming home again to write the sequel.

I think I had a feeling though, because I wrote it as a non-sequel first with different names, that I would go ahead and make it a standalone book, so if people didn’t read “Qualities of Light,” it wouldn’t be a problem.

Are you a plotter or a pantser?

Well, you know from all my years teaching at Grub Street that I teach storyboarding, and that’s definitely a plotter kind of approach to life. And so, what I do usually is I start out with an idea for a book, and I storyboard it, I diagram it.

I do the W structure and I work with a storyboard until I have a rough flow to the plot, and then I start to write. When I’m writing, I’m totally a pantser. I don’t have any real direction except trying to follow this map of the storyboard of the W. But there’s a point where the pantser in me gets totally frustrated, because I’ve got hundreds of pages and I don’t know where I’m going. So then I have to go back to the storyboard, like my map, and ask myself, “Am I writing the same book as I started out, or has it taken a completely different turn?” In which case I have to redo the storyboard a little bit to make the two match.

So I think I’m both. I go back and forth between how the story is informing me, which is the pantser part, and what I want from the story, which is the plotter part.

And for those who don’t know the W structure that you teach, can you just say what the points are of the W that you map?

This isn’t mine. It’s an old, old method. I think Joseph Campbell was the first person that talked about it in kind of a Hero’s Journey idea, which is funny because my book’s like a Heroine’s Journey. But the idea is that you have to have a series of turning points in the book in order for the plot to keep tension. And the books that I find that drop kind of tension in the middle, for instance, that deadly middle section that a lot of people as writers really suffer with, and readers too, is because there’s no turning points in that section. So the W actually visually allows you to see where your turning points are.

And there are five points in the W: the beginning, a lower one, then a higher one, then a lower one, then the end. And each of those five points are major events, outer events that are pivots. In other words, because of those events, the rest of the book happens. They’re like turning points.

Not only in plot are those five points important, but also in character development. So there’s a kind of predictable pathway that characters can follow using those five points, and they have to face certain things.

There’s a denial that happens in characters, as you know, as many writers know, and they hit different levels of denial during that process through the W. So they start out with a certain belief, and it’s usually a status quo belief, a certain idea that life is this way. When they hit that first point, which is the first lower part of the W before it turns up again, they’re facing that belief in a certain way and they decide to accept or not accept, and then they travel upwards to the third point because of their reaction at the second point. And the third point actually creates the fourth point, and then that creates the ending.

So when I do a W, I work back and forth. I work from the beginning, seeing how a character would transform during those five points, and then I start with the end and I work backwards and see, “Does point four naturally evolve to point five, does three evolve to four, et cetera?”

And so my W, it’s just a way for me to keep out of the weeds, I think. Because in writing, you get … Especially a book, you have 300, 350 pages, and you can lose track of what you’re working on really. You can lose track of the trajectory of each person. So, the W has saved me so many times. I know that a lot of people have used it from the classes that I’ve taught, and it really helps you just orient. But it’s just a map. It’s an artificial device. You have to actually be able to carry the story via the traditional writing tools that you know as a writer, but the W, the storyboard helps you when you get lost.

And you do a W for each character as well?

I do. I have three point of view characters in this novel, A Women’s Guide to Search and Rescue. So I did a plotline on the W, and then below it, I did another W for each of the three main characters, so I’d have four W’s total.

And then sometimes, I use a fifth W for the setting. The setting in this book changes. It becomes a character. It starts out ominous with the storm, and then grows more and more ominous, so it’s kind of paralleling what’s happening with the plot. I charted that on the W as well to see how the setting itself as a character would change. That was really fun.

So, you have this fabulous writing book that many people use religiously called Your Book Starts Here. And you have your weekly newsletter with craft tips and exercises that I always look forward to reading. Have you ever struggled with following your own advice?

Oh God, yes. Yeah, I’ve gone through the deep despair that most writers do and the challenge of, “Will this ever see the light of day, and will this ever work?”

I think people teach because they need to learn. For me, I really needed a structure, I needed to learn structure in my writing. So that’s why when I got the W in my toolbox, I thought, “Oh my God, this is fabulous.” It helped me, so then naturally I wanted to share it with other people, and that’s how it became something I taught. But yeah, I’m just like everybody else as far as writing. I go up and down. I have times that I’m crazed by it and other times that it’s really dead in the water.

Was this novel a little easier after writing Qualities of Light?

No. It was much harder. It was three points of view instead of one. It was about all kinds of topics that I had been kind of afraid to talk about in Qualities of Light. That book is a YA book. I think it’s a simpler story than this one. The relationship between parents and their kids was really important to me to work with in this book. Then the found family idea, that was another one. And then women heroes, the idea that we can rescue each other and rescue ourselves at the same time. These are all very big topics for me. And I think in Qualities of Light, I was more just working with the relationship between Molly and her father, who’s a very big feature in that book, and then Molly and Zoe, her first love. So it was much simpler. And when I got to this one, this one took 10 years. It was a really long, long process for me to figure out, “What did I want to say? What was this book really about?”

Mary Carroll Moore is a GrubStreet instructor and the bestselling author of 14 books in three genres, including the New Hampshire award-winner Your Book Starts Here. Her new novel, A WOMAN’S GUIDE TO SEARCH & RESCUE, a thriller-family saga combination, will be released in October from Riverbed Press. Learn more at www.marycarrollmoore.com. Join Mary’s Friday Substack, “Your Weekly Writing Exercise” at https://marycarrollmoore.substack.com/.