Photo by Drahomír Posteby-Mach on Unsplash

An editor once told me I needed two yesses in my writing life to be a published novelist. The first yes was from an agent. “Pass that gateway,” he said, “and you’re halfway there.” But I’ve had three agents, so I now know there’s more to the game than that.

My first yes came in the late 1990s with a nonfiction project I was asked to join. A Men’s Health editor was looking for a writer. As a side project, he wanted to pitch a book on health and eating. I’d just been featured in USA Today on the very topic, thanks to my Bay Area cooking school. A cook by profession, I’d also worked as a part-time food journalist, collaborating on two cookbooks that sold well.

My agent, whom I’d never meet except by phone, had worked with the Men’s Health project editor on other books. The editor and I drafted the proposal, the agent revised it, then sent it out on submission. Success! We got bids from publishers, settled on a medium-sized press that distributed with St. Martin’s, and had great direct-mail sales. The advance was lovely, the rights even better.

Agents were gods.

That book sold well. Royalties continued for ten years post-publication. The publisher offered me contracts for three more books. The agent negotiated reprint rights. My relationship with him was fine, pleasant. Years passed. One day I got a call—my agent was retiring. He offered to refer me to a colleague, a principal in a large NYC agency. A star signer. I’d heard of this man. By then I knew how hard it was to get an agent—so once again, I felt lucky to be lucky. My second yes.

But I didn’t know enough yet to be anything but thrilled, to look beyond this new agent’s credentials, to his particular communication style or his interest in my career. I received his contract, signed it, and waited. I sent him ideas for the next book. I waited. I thought another yes was all I needed to pave my golden future in publishing. After time passed with zero response, I realized this second agent had just done his friend a favor, took me on because of my first book’s good sales. I fired the guy.

Writing friends were aghast. “Do you know how hard it is to even get in the door of an agency at that level?” I didn’t care. Not seeing eye to eye, not experiencing the communication I believed should happen between agent and author, felt like reason enough to part ways.

I decided I was done with agents. Who needed them? I could sell my own books. And I did. I sold two more nonfiction books to the publisher who’d backed my first. Two more in a different genre were bought by a small Midwestern press. My first novel was picked up by a Florida publisher. None of these contracts required an agent. I had books traditionally published, I got good reviews, the books made money, readers liked them. I was on the right track.

During the pandemic, though, I began to question my certainty. I was working on my second novel, a bear of a book, and it was in its tenth revision. The Florida press wanted first refusal, but I wasn’t sure. I wanted a broader readership. I wondered if that meant finding an agent again. A writing friend who took a class from an industry professional told me querying required 75 attempts for one yes, an average querying time of one year.

Even with these facts, I grossly underestimated the research and time required: reading articles (“How I got my agent”) and listings on #MSWL (Manuscript Wish List) and agent interviews, checking titles from each agent’s list, following their Twitter threads, looking up sales in Publisher’s Lunch. A mountain of work. How lucky I was to get two agents handed to me, without any effort! But I like goals, I like new challenges. So, I set an objective of querying 50 agents in nine months, as a test. If my experiment flopped, I’d keep selling my own books, sans.

A friend suggested I pay an editor to refine my query letter. Even more work, money too! But I saw the wisdom. The paid editor helped me enormously. I sent it to the first ten agents on my list, then created a wall chart—50 names listed along the left margin with columns for agency name and contact information, date queried, date sample sent, date full sent, and end result.

The first batch elicited requests for sample pages and full manuscripts. Great! But the first ten full requests came back no’s. I stopped the process. If the query worked, but the manuscript didn’t, could I revise even more? Some of the no’s included feedback that made sense; I wanted to make use of it before I sent out more queries. Further revision took more money (editor) and more time. I attended conferences, like GrubStreet’s Muse and the Marketplace, and refined my agent list. I studied acknowledgements pages in books I loved (where agents are often thanked), scoured Twitter for agent threads, read more books on my chosen agents’ lists.

My wall chart helped. Over 50 percent of my queries resulted in requests for samples; about 50 percent of those resulted in requests for a full. That cheered me; I was doing something right. In month nine, the last month of my test, I received my first real hope: a positive response from two agencies that read the full, plus an email from a third agent who read it and wanted a phone call. I gave her my cell number and we set a time.

That morning, I went shopping—I was in a daze of hope and pushing down that hope. When I got home, I realized I’d left my cell phone at the store. I raced back. Luckily, someone had found my phone. I got home just in time to breathe a little, then receive the agent’s call. She made the offer. My third yes!

My past experience had clarified what I wanted. I wasn’t willing to sign with just anyone to say I’d achieved a goal. I knew I could publish on my own. I’d done it before. But now, I wanted partnership, I wanted someone who could help me shape the rest of my fiction career, educate me on the changing industry, champion my books.

My current agent and I have worked together on two novels now. Today, I know it might take more than one or two or three yesses to get the agent best for you and your writing career.

For those of you just starting out, here’s my advice on the agent game:

- Plan for a marathon instead of a sprint. One of my students queried ten agents and got all no’s. He came to me, ready to give up. I told him, according to the 75-agent rule, he was only one-seventh of the way there.

- Expect rejection—it’s part of the game, so flow with it as best you can. Paper your bathroom walls with them. Circle good things agents say in their rejections because, accumulated, those can mean a lot. I made a list of the positive feedback and kept it next to my wall chart.

- Don’t query your top choices first. You’re still learning the ropes, you may find you have more revising to do, and you don’t want to blow your one chance. Wait until you’ve gathered the rejections, gotten a feel for how it goes. (I didn’t heed this advice and blew my chances with someone I’d courted for years.)

- The query is the first gate you have to pass and you can, with great results, if you get help to make it as strong as possible. Think about it: If an agent gets 1,000 of these a week, what stands out in yours? Get feedback from writer friends, take a class at GrubStreet, hire an editor to hone your query until it sings. You’ll be glad you did!

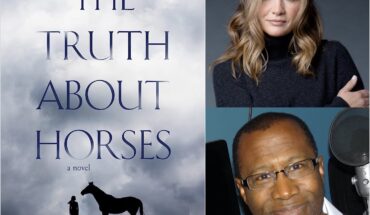

Mary Carroll Moore’s new novel, A WOMAN’S GUIDE TO SEARCH & RESCUE, a thriller-family saga combination, will be released in October from Riverbed Press. Find out more at www.marycarrollmoore.com on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. Join Mary’s Friday Substack, “Your Weekly Writing Exercise” at www.marycarrollmoore.substack.com.

1 comment