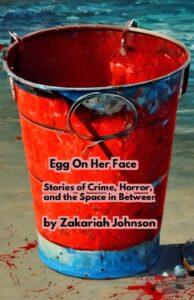

Zakariah Johnson’s Egg on Her Face: Stories of Crime, Horror, and the Space in Between is a gripping, genre-bending short story collection that will take you to unexpected places. These sharply observed stories focus on the struggle to survive in desolate sometimes surreal settings, bringing to mind the work of Jack London with a dash of Black Mirror.

Zakariah Johnson’s Egg on Her Face: Stories of Crime, Horror, and the Space in Between is a gripping, genre-bending short story collection that will take you to unexpected places. These sharply observed stories focus on the struggle to survive in desolate sometimes surreal settings, bringing to mind the work of Jack London with a dash of Black Mirror.

“For those of us who continue the labor of love that is the American short story,” writes Bobby Mathews, author of Living the Gimmick, “Zakariah’s new collection shows us that the art is not lost—it is, in fact, in damned fine hands.”

C.W. Blackwell, author of Song of the Red Squire and Hard Mountain Clay notes that “Zakariah writes with a keen eye for the strange and melancholic aspects of our human experience. With a steady, practiced hand, his stories transport us somewhere we’ve always known existed but could never find on our own—liminal spaces just beyond our collective imagination.”

I heartily agree! I was thrilled to speak with Zakariah about his stories’ take on survival, dystopias, Thomas Morton (the founder of the pagan, free-love colony that became my hometown of Quincy, MA) and so much more.

Emily: The stories span a wide range of genres, from historical to crime, dystopian, horror—even a ghost/crime story. What common themes did you have in mind when putting the collection together?

Zakariah: I assembled the collection to fit the premise “you can escape from any trap, as long as you’re willing to gnaw off the right limb.” Every story fits that theme in some way. Egg on Her Face is about the costs of staying alive, or true to yourself, and what the characters are willing to sacrifice to dictate life on their own terms.

Egg on Her Face is a wildly imaginative collection, filled with so many different settings: bleak wildernesses, dystopias, a desert with strange creatures and more. Where do find your inspiration for these worlds?

Thank you, so much! I guess bleak wildernesses have always attracted me—the tundra, Namibia, the Steppes, western Kansas, places like that. Places in the world that appear empty when you’re there, but where the scarcity of people makes those that are present more likely to interact with each other, for better or worse. The ghost story in the collection was one I thought about for twenty years after seeing the headstone described in it; it took me that long to figure out how to get across the same unease it made me feel in reading it.

I particularly loved “Ambuscade on the Aptuxet Trail,” the story about Thomas Morton: founder of the pagan, free-love colony of Merrymount—now my hometown of Quincy, MA. When my kids had their school fields trips to Maypole Park in the Merrymount section of Quincy, I had no idea what actually once went on there. This story brings that slice of the history so vividly to life; I’d gladly read a whole novel about it. What drew you to this subject and have you thought of revisiting it for a longer work?

Thomas Morton is the best, isn’t he? But it’s obvious why they never taught us about him in school! Imagine if a free-love (and probably gay) socialist pagan was the basis of our founding myth instead of the Pilgrims who ran him out of town. What a different country this might be. It seems made up, but it really almost happened! He was here at the same time as John and Priscilla and all the others. Of course, I read Hawthorne’s wonderful take on Merrymount, but I put more violence into mine because that’s closer to reality. We have this idealized version of Pilgrims and Puritans that’s at odds with their brutality—they were still hanging Quakers in Massachusetts in the 1660s! I wanted to emphasize that the Pilgrim version of America—authoritarian, self-righteously pious, brutal against dissenters—not only wasn’t inevitable, but barely won out even in its own day.

I’d love to write more about Morton. I read his book denouncing the Plymouth colony—the first book ever banned in America—as background to the story and 90% of the words he speaks in the story come straight out of his book, including his insult of calling Miles Standish “Captain Shrimp.” There’s a lot more source material there. I wish he were better known; hopefully my story helps that happen a little, especially in Quincy!

“Laetoli,” your cautionary tale about the consequences of global warming, features a man struggling to survive after a catastrophic volcanic eruption. He’s up against not just this desolate world—where ash falls like deadly snow and temperatures soar—but also against the other people left behind. (It reminds me of the series The Terror, in which a group of explorers become stranded in the arctic and have to confront both nature’s power and the monsters that exist within themselves.) In spite of your story’s bleak outlook, you bring things to a moving ending. What would you like readers to take away from this story?

I’m glad you saw the hope at the end. I had one reviewer describe it as “depressing,” which I guess it is, but I hope not in the larger picture. There have been many “ends of the worlds” through human history. It’s probable someday, someone will die in the final one, but in the meantime, those footprints in the ash are evidence of a continuity of community, hope, and mutual aid stretching back uninterrupted for millions of years to a day when that family of survivors, possibly in a time before verbal language, walked together across the desolation of a volcanic eruption in search of a new life. The point is they did it together, which is something I hope people take from the story—we’re not lone wolves, we’re social beings and we always have been.

A short story can be harder to write than a novel, and you accomplish so much in a small space here. What’s your process for writing a short story? Any special tips for pulling it off?

I start with a basic idea, the “what if” question and try to build an action-based story around that. When the basic plot is set—usually in a page or less, I look for obstacles and threats for tension, for the suspense, and make sure to build those. Sort of like a steeplechase course—first build the track, then set up the obstacles. It doesn’t matter what the stakes in a story are, but to grab our interest there has to be a chance the protagonist will lose. And some heroes do.

“Defense for the Prosecution,” told in the voice of a cynical DA, packs a powerful message about corruption in our criminal justice system. It’s so convincing that it feels ripped from the headlines. What research or experience did you draw on to bring your corrupt DA to life?

The initial spark for this story was watching events in Ferguson, Missouri, after Michael Brown was shot, prompting the BLM movement. An aspect that surprised me was the redundant government structures, like courts and police departments, in neighboring small towns in Missouri that were arguably too small to support them. Residents either couldn’t or wouldn’t support local government with taxes, so the police and courts morphed from serving the public into preying on the public to pay for their own upkeep. The purpose of the city police wasn’t to keep the peace, it was to fund their own jobs through arrests and fines, a modern-day Sheriff of Nottingham situation. Looking into that uncovered an endless chain of these structural abuses built into the system to sustain itself for the sake of sustaining itself—the Brady lists, judges and prosecutors swapping roles in each other’s courtrooms, prosecutors afraid to prosecute police they rely on for testimony.

Every abuse mentioned in the story is happening somewhere; it’s all true. And of course the people most aware of the problems have the largest incentive not to fix it, also true in most cases. The story was picked up for its original anthology, Under the Thumb: Stories of Police Oppression, by the great S. A. Cosby, one of my favorite crime writers, which still thrills me.

In keeping with our blog name, was there a darling that was especially hard to kill when you were working on these stories?

I intentionally kept the collection as short and diverse as I could, also sticking to the chew-off-your-own-limb theme. There were a couple stories I considered that just didn’t fit the theme or that mirrored a detail in another story, so they had to wait their turn. For instance. I have another story about a volcanic disaster in New England—a tidal wave at Hampton Beach—but I didn’t want it detracting from the impact of “Laetoli,” so it had to wait its turn.

What are some of your favorite reads?

The short-story writers I always seek out include Mariana Enríquez, C.W. Blackwell, Nikki Dolson, J.B. Stevens, and…well, it’s a very long list! I recently read The Best American Mystery and Suspense 2022 short-story collection edited by Steph Cha and Jess Walter, and I’d recommend that to anyone looking for new authors to explore. I’ve been reading a lot of novellas lately, 100 to 150-page stories you can finish in a single evening, which I enjoy doing. A lot of small presses are putting out great crime and horror novellas these days—Alien Buddha, Shotgun Honey, Crooked Lane. It’s a golden age. For readers looking for that sweet spot where mystery and horror collide, Cynthia Pelayo, Gabino Iglesias, and the perennial genius, John Connolly, are all turning out amazing, inspiring work. (Connolly’s Charlie Parker series is based in Portland, Maine.)

What’s next for you?

My first full-length novel—MINK—is coming out in 2023 from Wordwooze Publishing. It’s going to be in three formats: print, ebook, and audiobook, which is super exciting! It’s a mystery-horror hybrid set on a Wisconsin mink rank targeted for destruction by the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) in the early 90s, and it’s filled with 90s cultural touchstones and nostalgia, but bloody. I’d describe it as The Monkey Wrench Gang meets Psycho. It asks when is violence justified and when is it just an excuse for demanding your own way? These are old questions, but they interest me. Hopefully others, too. I’ll be reading a section from it at the Seacoast Noir at the Bar event in Portsmouth, NH, on March 8.

Zakariah Johnson plucks banjos and pens horror, thriller, and crime fiction on the banks of the Piscataqua. The diverse topics of his fiction reflect his background working on four continents in jobs ranging from newspaper reporter to archaeologist to commercial fisherman. At one time or another, he has faced down hungry polar bears, canoed across international borders, and hitchhiked the Kalahari. Johnson’s first book, the short-story collection Egg on Her Face: Stories of Crime, Horror, and the Space in Between was recently released from Alien Buddha Press. He can be found on Twitter and Instagram at @Pteratorn (it’s a bird).

2 comments